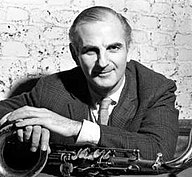

There have been many fantastic documentaries showcasing legendary musicians and venues. Oliver Murray’s Ronnie’s – now playing at DOC-NYC – manages to do both, as it profiles the London club Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in Soho, as well as the tenor saxophone-playing jazzman that founded the iconic venue.

Ronnie’s finds a way to balance its profile of Ronnie Scott, musician, with his jazz club that became the premiere venue in Soho where many musicians, even outside the realm of jazz, would make sure to play while in London. The archival performances in the film alone are something to behold, but the way Scott and his team found a way to intersect them in with telling Scott’s fairly tragic history that was itself punctuated by his very distinctive sense of humor.

Below the Line got on Zoom with Mr. Murray earlier this week to talk about what went into making a doc filled with so much jaw-dropping archival footage and unforgettable performances on top of Scott’s own story

Below the Line: What got you down the road making this movie about Ronnie Scott and about how long ago did you get started?

Oliver Murray: Iwas at the Tribeca Film Festival with my first film project called The Quiet One, which is about Bill Wyman. Some producers came and asked me if I was aware of Ronnie Scott’s, and of course, every Londoner, every London music fan is, so I immediately said that I’m a huge fan, but if you’re looking for someone who’s an absolute jazz fanatic, and knows the story already, I’m not the guy. I really felt with this one that what I did represent was a young audience — everyone knows Ronnie Scott’s the club, but I didn’t know anything about the man behind the name. I really felt it was a really exciting opportunity to tell a story that people have forgotten largely. He is a is a shamefully forgotten character in history, so I was very, very blessed to be given the keys to an extraordinary archive of material that came from all over the place and a lot of goodwill from musicians and people in the industry who, as you know, I think some of those performances in the movie are certainly some of the best musicians of the 20th century, and I defy anyone to watch the Buddy Rich scene…

You only get a lineup like that if they want to rally around the idea of telling the story of Ronnie. I think a lot of people had said “no” in the past, because he was a private man. I think they only wanted to do it if it was going to be done right, but then, as the years went by, I think what some of the contributors said that this was the last bus to telling the story. I was very, very fortunate to get such amazing goodwill from the record labels and the agents. A lot of these platinum tracks, as they’re called, go for huge amounts of money to be licensed in docs and movies and everything. I’d like to think that to a certain extent that was because we were making the film the right way and telling the right story. A huge part of that, obviously, is because of Ronnie’s legacy and what it means to all those people that holds the rights to this material. They know he’s a man who needed the next generation to understand what he built, what we enjoy on both sides of the Atlantic, even what he and Pete did with the musicians’ unions in America and in the UK. That foundation that they created almost is something that we’re benefiting from, maybe not this year, but in normal years, that cross pollination of musicians and musical ideas is in no small part down to them. Stories like that just fascinate me in the early weeks of the research. The problem was having to leave out the things that I really found interesting or the performances that were great. Some of the stuff we left on the shelf was undeniably great, but it didn’t fit the arc of the story that we were trying to tell. Here we are with with this movie.

BTL: Did Ronnie Scott’s club generally film all the performers that played there so they had that archive or was the footage from all over the place?

Murray: They did, but definitely every 10 years, the BBC would go in and and they would do something structured like that… well, as structured as jazz club management gets. Things like the Nina Simone performance and the Sonny Rollins performance, they were filmed, because both of those artists would go in and stay… Another fascinating thing I think about Ronnie’s was that they would turn up for a month at a time. Nina Simone would have month’s worth of gigs at Ronnie’s, almost like an artist in residence in a way. At the end of it, [they] very uncharacteristically said, “Let’s film it. I want this documented one way or another.” It was very haphazard of why they filmed, but it was usually because the artists knew they were going to get the best out of themselves after a month. They were obliged. It’s an awful place to try and film. It’s dark, the ceilings are low, it’s 200 people capacity at the best of times. In that opening scene, Oscar Peterson is literally melting. The amount of firepower of the lighting that they had to get on those guys and gals just to expose correctly was phenomenal, but worth all the pain and the hassle of making it work. I mean, it’s beautiful.

BTL: I’m amazed you actually were able to find BBC footage from the ‘60s and ‘70s, because I’ve always heard nightmare stories about the BBC reusing tapes. I’m not sure if it was shot on film or you found someone who videotaped it off television. How did you find that stuff?

Murray: It’s always very sad to see just how much is lost. In my sort of line of work, it’s really shocking what you see. The BBC Archive, I think, is the largest and oldest archive in the world, and I think maybe back in the day, it was fine when the people that built that archive maintained it. The moment you lose the expertise, the actual boots on the ground of the people looking after it, it gets tricky. I think archives everywhere have struggled to migrate to digital archives as well, and tiny little misguided error might mean that you digitize all of your material… like the DVD era, some people thought, “We’ll put everything on DVD and get rid of the masters.” It’s tragic. Even things that are obviously commercially valuable, like the Rolling Stones material from my first movie, a lot of the American stuff made its way to Europe, to places like Scandinavia, as part of newsreel packages, or say like a Danish television technician, when no one was looking would have a little feed out of the back onto a tape recorder in the studio late at night, just so that they could just as a fan watch it back. Some of that stuff is now the only place that you can find it, because the masters, as you alluded to, the video tape was ruthlessly expensive. That’s a long-winded way of saying it comes from all over the place, and you roll the dice and try and find the material. You go down a road that leads to nothing more often than not, but if two out of 10 times what you find is Miles Davis. He’s in the middle, sort of in that wild phase, that “flying close to the sun” kind of vibe. Sometimes, you find that stuff. Other times, you just find that’s technically… underexposed material… You swing big and you only need to connect a couple of times to find the magic that really delivers in the movie.

BTL: Did you have to do a lot of restoration or coloring to do? All of the footage looks amazing, as if it was shot last week.

Murray: There was. I’m so grateful to the team that I’ve worked with on both of my feature docs. It’s the same guys at Molinare in London. It’s that amazing invisible art of the sound restoration and the mastering and the grading or fixing the video interlacing or whatever it is. Even the scrappiest VHS stuff in there. There’s not a lot, but they make that look great. I think you embrace the medium as well, rather than trying to get it slick and glossy and all looking the same. I really enjoy embracing that sort of collage effect. I think people enjoy that aesthetic, that sort of almost mixed media. It’s almost like a scrapbook of London in a way rather than this perfectly rounded edges everywhere. I like it to try and feel as textured is the real thing that I had in my hands. I always try and hold onto that. If there’s a dog-eared photo, I like to keep it rather than airbrush it all out. That’s a little bit of my experience of going into people’s attics or looking in their boxes in their garages and picking each little item out one by one, that’s the only way to do it.

BTL: It reminded me a bit of the Peter Jackson doc about WWI where he used original archival footage and colorized it, added sound and bring it to life. In a similar way, I’d love to see Ronnie’s in a theater, since I think that atmosphere would be better for seeing the movie. Hopefully, sometime down the road.

Murray: I hope so. Obviously, at the moment, we have problems, and only a lunatic would buy this film for theatrical release right now. We had the luck that Ronnie Scott seemed to have throughout his career as a club proprietor, it sort of rubbed off on the film a little bit, because our cinemas in the UK have been shut for most of the year, but we had a six-week window right when we were ready, and we released it in limited cinemas. Usually, we’d try and have a bit more structure to how we released it. Literally, the skies parted for us a little bit, we had this window and we went for it. It was fantastic just to see it on the big screen, and also just to hear it. The amount of love that guys put into mixing that for the cinema was fantastic. Honestly, it’s the closest thing to being there.

BTL: I want to ask about working with some of your other craft and technical people, particularly Paul Trewartha, your editor. I’m not sure if I’m pronouncing his last name correctly.

Murray: He’s from Cornwall in the Southwest, so it’s almost like a half-Welsh, half-Gallic pronunciation. It’s a strange part of the world down there, but he should really have a piece of writing credit with me, because he’s fantastic. It was our first movie together and hopefully, we will do a whole bunch more, because he’s a storyteller. He is very technical, but at the same time, it was all conversation about story and coming from a music video and a commercials background, that’s not traditionally the kinds of people that I would come into contact with, so it was really fantastic. I felt like I was really working with a proper filmmaker/storyteller.

BTL: I like the fact you were able to balance the story of Ronnie the man but also the history of the club at the same time and go back and forth. There must have been a lot of stuff you had to leave out, so what was some of the stuff you really wanted that had to be cut to keep it under two hours?

Murray: The thing I was most happy with, once I had some distance from it, was seeing how the music actually supports the narrative, the ups and downs of the club and his life, although there were some fantastic performances, like Jeff Beck playing A Day in the Life by himself on guitar. It’s unreal. That’s quite late from the ‘90s. I mean, check it out, he makes that thing sing, it’s unbelievable. There just wasn’t room for it narratively. It’s just having that discipline I suppose. You can put it in the timeline for a couple of days, but if it doesn’t hang together as a piece, then it has to go. I guess with each film, and the more my team and I get to work together, the more we have this shorthand of getting to the end result quicker, I suppose. There wasn’t a huge amount that I didn’t want to get in subject-wise. I think you can tell that Ronnie’s family and Pete King’s family, and the club were incredibly open. There’s no holding back of any of the skeletons in the closet that we weren’t allowed to go near. I think that was very therapeutic for both families to talk about that so openly. I felt very blessed that I was able to tell the story that I wanted to tell, which wasn’t always easy on my first film, given it’s on the Stones.

BTL: I liked that movie and didn’t realize before we started speaking that you had made that as well. I like the fact that you actually made a movie about an archivist who actually had everything you might need right there in his library.

Murray: In a way, there would be no Ronnie’s without The Quiet One, my first movie, because of the lessons I learned in the archiving, and I knew where to look a lot better. It’s a very special set of circumstances that I’m able to tell the story of the club and then be able to take a very emotional turn and really get into Ronnie’s mental state, which I think brings the whole thing full circle as to why he did it in the first place. I think he needed music like people need medicine to deal with his mental afflictions. What I think is really fantastic is that there’s so much negativity at the moment with all the things that everyone’s dealing with COVID, but if this film can be a message of how gathering together to listen to music or tell stories or go to the cinema, this stuff helps people that are going through things. I think that was where I found my way into Ronnie. I totally get what he’s coming from. This film’s a love letter to that club, but it’s also a love letter to live music and that atmosphere, that togetherness, because I need that as well. Hopefully, when we come out the end of this. Everybody’s got their own Ronnies somewhere, in that local neighborhood, whether it’s a bar or a cinema, or anywhere that we gather. I hope that this film flies the flag for those places, and we look after our venues.

BTL: I do want to ask about the incidental music that didn’t come from the performances. I was curious how you approached that, since you have so much music available to you from the club and the performances. What did you want that other music to add?

Murray: Again, another real huge piece of luck that I was incredibly happy about was that we got Alex Heffes on board. He’s a fantastic composer. He’s done all sorts of stuff. We’ve lost him to LA now, he’s over there, but he came back. In terms of a brief, it’s really hard to know where to start when you’re saying, “Okay, here’s the line-up of musicians…” There’s no easy cue in that, because he’s either got to get us from Sarah Vaughn to Buddy Rich. It’s a proper jazz score, but the instrumentation and the choice of musicians that he brought in was fascinating. I always love just being a fly on the wall of that part of the process, because it’s one of the first moments where you’ve done enough work that for better or worse, there’s a film coming down the pipe. It’s not going to fall to bits, and you can start to get a bit of objectivity as a collaborator. Alex comes in, and once you know that, tonally, he’s understood where you’re coming from, then he’s also just making it 10 times better than you ever imagined. That’s just like the best feeling. That’s a big leap of faith and a lot of trust that the director has to put in the composer. If you’re on their shoulder the whole time, nervously trying to control it, it’s never going to work, especially in this kind of environment. This sort of free-flowing improvisational score. I think he just did the best job. I hope I can work with him again, as soon as possible.

BTL: How much of the work did you have to do over the last 8 months under COVID quarantine to finish the movie and have it in cinemas?

Murray: We were close. Creatively, I was pretty much done, but then there’s still the logistics of licensing and mastering, rescanning and all that stuff. That wasn’t done at the time. Actually, when people started whispering that there was this COVID thing coming, it got it over the line. Everyone’s quite tired at the end of the process, and you’re really existing on fumes, because budget has gone in unexpected places. It kind of made us just just get it done, because it just felt like everyone was trying to get things done. This is still an independent movie, who were in the same place where Amazon and Netflix, they’re all trying to take the suites over and get their shows together. So we got it in the can by then, and then I’d very recently been going back in and doing the final mixes and the masters and things now that we know where it’s gonna go. There’s always something. Once it’s finished, as you know, it’s pointless making these things if you can’t get it out to people. The job continues and if anything, gets gets even busier at this point, because when there’s something you’re so proud of about to launch, you want to make sure that as many people that are interested get to watch it.

BTL: I’m sure this will be picked up by a PBS or someone else, but I do hope it’ll have a chance to be shown theatrically here down the road, because it’s something that would work really well in that environment.

Murray: I hope so. I’m interested in that you watched it twice, because what I found while I was making it and what people have said watching it twice is that it definitely benefits from a rewatch as you see other things in it. You can relax into knowing what you’re in for, and the details of what’s in that archive, I still get a kick out of watching it, especially when I got to see it on the big screen, because you see things that I didn’t see, and I’ve looked at it a hundred times. I hope we’ll find a big screen, and I hope maybe it will find a big screen even after it’s available on the small screen. It’s almost like gig in a way. I think people would go out to see this movie properly in five years, ten years, is the plan. I’m interested to see what you guys think of it over in the US because it’s such a London-centric story and about an institution that we’re incredibly proud of. I’m really interested to see if there’s enough there to make people curious, who don’t know what Ronnie’s is. To me, Ronnie’s is to London, what CBGBs is to New York, for instance. It’s that important to the infrastructure of the city, of how it came together.

Ronnie’s is currently playing at DOC-NYC, which runs from November 11 through 19.