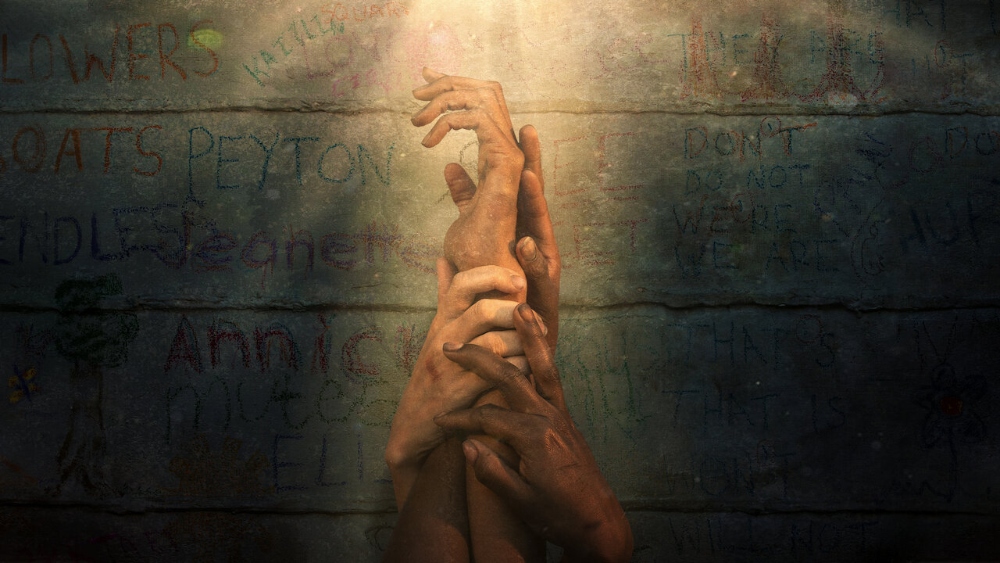

Alanna Brown made a decision. An actor-turned-aspiring filmmaker, she’d written Trees of Peace, a tough, emotional drama about a quartet of disparate women – a Tutsi (Bola Koleosho), a nun (Charmaine Bingwa), a pregnant Hutu (Eliane Umuhire), and an American (Ella Cannon) — hiding in a basement during the violent Rwandan genocide in 1994, and she was going to direct it — no matter what.

That “what” included nine years of ups and downs, nine years of minor successes and major disappointments, until — finally — she secured funding, shot the film, and eventually landed a distributor. And it turned out not to be just any distributor, but Netflix, which put Brown’s powerful film in front of hundreds of millions of people worldwide.

Below the Line recently caught up with Brown, who has also worked as a writer on the Starz series Blindspotting, and she discussed her shift from acting to directing, the long path she walked to realizing Trees of Peace, and what she plans to do for an encore.

Below the Line: When you were a kid, what did you want to be when you grew up?

Alanna Brown: I always loved writing. I remember writing my first “movie script” when I was probably 11 years old, and it definitely didn’t look anything like an actual script. It was, in my mind, what I thought of movies. I could probably pinpoint it to 11-13 years old. I started writing mainly prose, short stories, [and] poetry, and continued [my] love of writing and storytelling.

BTL: Which came first for you professionally — acting or writing?

Brown: Unfortunately — and this is probably true of a lot of artists — I wasn’t raised in a household where it was, “Yeah, go be an artist.” It was, “No, go to college. Get a degree and a job. Be sure to support yourself and have a meal.” So, I went [and] got a Communication Studies degree. It was never fostered in me to be creative, but, ironically, my mom put us kids into acting because she was like, ‘You need money for your college fund.’ That introduced me to the world of cinematic storytelling from a young age.

I quit acting in high school. I wanted to hang out with my friends and I had to do my homework. I didn’t want to be going around to auditions anymore, but I had that bug already. I’ve been on sets and had a taste of that magic. When I finished my Communication Studies degree, I was working in a stuffy job and hated it. I had that creative bug and I was like, ‘I can’t do this. I’m going to go. I need to do something creative. I have my SAG card, and I’ll try acting.’

BTL: You were how old then?

Brown: That was in my mid-20s. I got into a scene study class, I got an agent, and I started going out. For the scene study class, the teacher assigned us to write a five-minute short, in which we would cast ourselves and then shoot it, so we could build up our reels. That five-minute short turned into my first short film, which was 28 minutes long, and I was in it for 30 seconds.

When I started writing it, the story took over. It wasn’t about the acting for me, it was just about the story, and my roots in writing. I thought, ‘Oh my God, I’m writing.’ I had written prose. Movies, cinema, and TV… it just clicked. And it was like, ‘Oh, my God, yes! This is the thing.’ It was [the] acting first, sort of professionally, I guess.

BTL: What led to directing? Did you think to yourself, “Hey, if I’m going to write something, I should direct it, too?”

Brown: Yeah, exactly. As I was writing my short, it was so visual. In my mind’s eye, I could see it very clearly and I just felt like I wanted to make it. I thought, ‘I’m not going to stop at the page. I’m going to go get this on screen, and get it made.’ So, I went about figuring out how to make a short film. I sat down with friends in my scene study class who had made short films and basically started interviewing people — asking questions, reading books, and soaking up everything I could to get a crew together. I financed it myself and produced it. I found locations, and actors who were mostly from my scene study class. Then I put it together and fell in love with directing. It was like, ‘Okay, this is also what I’m doing now.’

BTL: You’re a woman as well as a woman of color. You were trying to make a film about Rwanda. How many people told you “No” or suggested you try something else? And, who told you “yes” and championed you when it came to directing?

Brown: When I was on the path, the script for Trees of Peace was what got me an agent and a manager. As I was on that path, I always knew I was directing it and I dug my heels into the ground on that. Whenever I met with an agent [or] took any meetings, it was always, ‘I’m attached to direct this.’ People, surprisingly, seemed to accept that. They were probably secretly thinking, ‘Yeah, good luck with that. You’re never getting your movie made.’ To my face, they were [like], ‘Okay, that’s great.’ They seemed encouraging or positive about it.

My agent at the time — I now have a new agent — but even when I switched over, he said, ‘Great, you’re attached. That’s awesome.’ People seem to be totally fine with it. No one said, “No, you shouldn’t direct this. You should just try to sell the script.” Again, maybe they were just thinking, “It’s not going to get made anyway, so it’s not a battle worth fighting.”

As I went along, and over the nearly nine years it took to get this film to where it’s at today, there was a ton of rejection, so much rejection [in] trying to get financing, and then ‘You will need an A-list cast to move the needle on that.’ I thought, ‘No bankable talent is going to trust me with their work.’ That was not happening. It’s like, “Which comes first, the chicken or the egg?”

BTL: If you can’t get talent, then you can’t get financing. And if you can’t get financing, you can’t get talent…

Brown: It was a gauntlet of doors getting shut in my face. I continued to try, doing various strategies that failed, pitches that I came up with that had a good look early on. I did a proof-of-concept trailer, and then I said, ‘Screw it. I’m going to shoot this on a tiny micro-budget. Ava DuVernay shot her first film for $50,000, so I can do it, too.’ I raised $65,000 on Kickstarter, and I had a mind to just go make it myself. I was tired of the rejection and thought, “I’m not waiting for permission anymore. I’m going to go make it.”

I had a number of producers at that point — I’d say maybe three — who felt more like serious producers, because there are the people who are [like], ‘Oh yeah, I’m a producer,’ and then it turns out that they don’t really know what they’re doing. They don’t have the connections, or even the know-how to produce the movie. Those people came and went, and then I had a few agreements with various producers who seemed passionate about the project, but unfortunately, the problem was above them. There was no money and no star talent.

That took us a couple of years of navigating through the attachment deals that I’m sitting there with, waiting for the producer to do something for the extent of time that we’ve allotted, then the time runs out and I move on. Finally, [I met] Ron Ray, who is the lead producer on this film, and it was his first feature as well. We have a lot in common. He was similar to me in that he was like a dog with a bone; he wouldn’t let it go. He believed in the project. He was passionate about it. He had the network that I didn’t have. He had access to private equity financing, knew some people, and was able to really put his energy behind me with this film and get it made.

BTL: Why was this film so important to you that you were willing to spend nine years of your life working on it?

Brown: That’s a good question. I was interviewing a woman who founded an initiative in Rwanda to help rehabilitate women survivors. In preparing to interview her for an article I was writing a long time ago, I started discovering stories of survivors, women, and people in hiding. It was harrowing and so compelling to me. In finding that Rwanda has the highest percentage of women appointed to government [roles] of any country in the world, I was absolutely floored by that and I felt like nobody knew. It was this profound piece of information that said so much and nobody knew.

For me, as a woman of color and as a Black woman living in the United States, where the women’s movement is still very much at play and equity is still something we’re fighting for — Roe v. Wade was such a devastating loss for women — that fight is still real. Even as I set about making this or writing it nine years ago, that was very much the case. The story of the women in Rwanda, while it may seem far removed, it’s close to my heart. It resonated with me and feels personal to me. That was what drew me to the story. Also, larger macro versions of the story have been told — wonderful, beautiful films like Hotel Rwanda and Sometimes in April, but I felt like the women’s side of the story had not been told, and it needed to be.

BTL: Let’s go into the basement. It’s a movie, so it was a set, but I’m assuming you had to make that room as claustrophobic as possible for the actors in order to elicit their best performances. Did you block everything out in advance and know all the camera moves heading into each day of shooting?

Brown: It was 20 days in a box, basically. The cinematographer and I — Michael Rizzi; he’s wonderful — prepped for, I’d say, at least six weeks. Maybe it was eight. The first day of prep, I showed up at his house. He had this small, one-square-foot clear, acrylic box that was to mimic the set for pre-vis. He also had four Barbie dolls that he brought to the prep. We used those Barbies and the box for our pre-vis, to figure out how we’d configure our shots. We had everything lined up and ready to go.

Of course, we ran into problems on set, but that’s always the case. We prepared, prepared, prepared. We had everything down… transitions, camera moves. Our shot list was very robust. I had a strong idea of what I wanted for each scene, but as I did my script breakdown, it just became crystallized and the two of us together were able to map out the whole shoot. Also, we’d run it by one of our ADs who would go, ‘Okay, we can get these shots,’ or ‘We can’t.’ I did the same thing in my proof-of-concept trailer.

We had the production designer create a modular set. It was a six-piece set — four walls, a ceiling, and a floor that all came apart. We also had a second trick floor, I guess you could say, that had a hole in the middle for those 360-degree shots. The camera went through the middle of the floor. We had a second half-set box which was in an actual room under the floor so that the house was a set on risers. Below that was a half-box just for the shots for when the camera moves below the floor and then moves back up at the end. Taking the walls apart enabled the camera to get any angle we needed, to get in there from above, [or] on sticks from below. That’s pretty much how we created that.

Even though there would always be one wall off, the actresses did definitely feel boxed in, so to speak, during the shoot, and that helped create the claustrophobia. We were also lucky, because we were on a set and not on location, to shoot in complete linear order, which was great for all the other aspects of the film and for the actresses’ performances.

BTL: What did your cast bring to the table from your perspective?

Brown: They were fantastic. I call them the one-take wonders. We were so limited on time. We got, max, three shots for any setup. Sometimes it was one shot, one take, and move on. From the first take, they were magic. They were great. They each brought their vision for the character. They were wonderful. It was cool having written the script and then directing it, but there was still so much discovery, which was surprising to me. As I went through with my director hat on and started to break down the script and dig through the subtext and the events of every scene, I was discovering more stuff.

Once we got to rehearsal with the actresses and Tongayi, the actor who plays Francois, they had questions, and more to bring. It was beautiful. It was amazing to me, what they brought. The very first scene we rehearsed, I’m like, ‘Okay, I’m ready to go. I have my kit of director things, ideas about what will make this work if it’s not gelling,’ and boom! That first rehearsal, they had it. I was amazed that they took these characters off the page and brought them to life so seamlessly. The woman who plays Annick, Eliane Umuhire, is Rwandese, and she lived through the genocide at nine years old. I’m sure that was big for her as well.

BTL: You visited Rwanda in 2019. How did that inform the story and the production?

Brown: That was a life-changing experience. It made the texture of the film tangible for me. I went to Rwanda kind of late. 2019 was long after I had done all the research. I had interviewed a survivor, who lives in L.A., years prior, and I soaked up all the things I could from afar. When I went to Rwanda in 2019, it reaffirmed my commitment. Not that it was ever in question, but it also reaffirmed the worth and beauty of the stories, as well as [their] necessity. The people in Rwanda… there’s warmth and beauty. It’s shocking that a genocide even happened there. They were so welcoming and warm. The people I met, their smiles were so full of life, warmth, and light.

Someone said, ‘Maybe that’s the gratitude for life after having lived through such a harrowing ordeal.’ There’s an appreciation for life in their DNA now. Visiting the Genocide Memorial site contextualized it for me. It made it feel tangible, more real. I put my hands on and stepped foot in that place. Not only that, it felt almost like a rite of passage, like I needed to go to this country. I couldn’t possibly direct this film had I never been to Rwanda. That feels almost disrespectful, and so that was a big part of it for me.

BTL: Once the film was completed, you took it on the festival circuit and sought a distributor. What does it mean to you that it’s now available on Netflix and practically the entire world can see it?

Brown: Amazing; it’s a huge dream come true. Netflix was always my number one goal. That was my shoot for the moon [choice], so it’s pretty astounding the film is on Netflix as an original, globally. It still blows my mind to think about what a small film it is. That process is crazy. As an indie filmmaker, every step of the way you think, ‘Okay, I’ve made it. I’m done,’ and [then] there’s another can of worms beneath that. It’s never-ending. You get to the distribution phase and this whole other world opens up, a whole other series of obstacles, more rejection.

UTA, the agency that did the sales, put together our market showcase. In COVID times, it wasn’t a physical, in-person market showcase as it once would’ve been. They did a digital showcase and sent it to all the buyers and distributors they felt would be potentially right. They had three days to click on the link and watch the film, then circle back with their answer. We got a ton of passes, only a handful of maybes. It was a matter of who’d be interested, [and] if we paired it with whatever packaging situation that’d lure them in. There were some of those, but it was mostly more doors slammed in our faces. It was a lot of, ‘Wow, that was a beautiful and powerful film. Beautiful narrative. We loved it. We will be watching Alanna’s career, but it’s too small. There aren’t names. There’s no nobody we can latch onto to try and sell this film.’

That was the problem throughout, from beginning to end. It was disheartening, and definitely a disappointing journey. Eventually, Ron Ray was able to get the film in front of the right people by knocking on doors and getting it to someone in acquisitions at Netflix who would take another look. That time, it was [like], ‘Okay, we think we can do something.’ Then it was, ‘Yes. we’re going to take this on.’ It was like a movie in itself.

That was a low point, and [then] ‘oh my God, we broke through.’ It seems unreal. It’s astounding that it’s gotten here. And the response has been beautiful. The people writing to me on Instagram, DMing me to say “Thank you” for how the film has moved them and touched their hearts. That’s one thing I was surprised by. I didn’t expect or think about that. I thought, ‘Okay, there will be [some] critical reviews.’ I figured there would actually be more criticism, especially of me not being Rwandan. I thought there’d be criticism of how there’s a white character in the room. Of course, she has a purpose, for me as a writer. [But] I haven’t seen any of that. It’s been mostly people thanking me for making this film. That is the biggest reward.

BTL: Trees of Peace is now your calling card. In a perfect world, what will it lead to? What do you want to do next?

Brown: I’m working on getting my next film set up. I’d love to write and direct that. This is my dream job, so that’s the goal. That’s what I want to continue doing. My next film is called Water Between Worlds and it is very different from Trees of Peace. It’s a magical realism love story. It was formerly titled The 29th Accident and it was on the Black List, so I actually wasn’t attached at that time to direct it. It was a script I’d written on the heels of Trees of Peace, and I just wanted to sell something. It made the rounds, and it never sold. Again, it was on the Black List and people really loved it. I reread it in the past couple of years and thought, ‘I love this. I want to make it.’ So, I just decided to attach myself and direct it. That’s what I’m doing next.

BTL: Will that take nine years?

Brown: I sure hope not. I sure hope it’s faster to set up than it was for Trees of Peace. It’s looking good so far. I can’t say much else about it, but it’s looking better than the last time. So, fingers crossed it goes faster.

Trees of Peace is streaming now on Netflix.