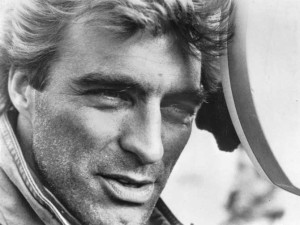

From writing, producing, editing and directing Jazz (1979), one of the most critically-acclaimed thesis films in the last 35 years, to managing one of the most polarizing pop culture icons of all time in Prince, Albert Magnoli has undoubtedly seen and done it all in Hollywood. From 1984’s Purple Rain, to 1996’s TV series Nash Bridges, and 1997’s Warner Bros. hit Dark Planet, Magnoli’s early film history challenged norms and pushed boundaries. At first glance, Magnoli’s story may seem run-of-the-mill: a talented director finding his way into the film industry and onto the big screen. But journey back to 1976, the start of his career, and you will discover a young and talented aspiring director with a camera, a dream and landscape-changing ideas.

A student of USC‘s School of Cinema-Television, Magnoli knew the techniques and information he retained from his collegiate years had a huge influence on his career. “What I learned at USC film school was extremely valuable,” he said. “It gave me a firm foundation technically, and provided me with a grounding that served me well as I ventured into the professional realm. Many times when I was on the set directing, or in the editing room editing, I would think back and rely on the things I had learned at USC, speaking to the professors and my fellow students. It was a solid, educational experience, and I draw on my time there to this day. The bottom line is this: I loved my time there, and I would not hesitate to recommend the experience to students considering the venture.”

With others from the same period at USC eventually entering the industry, including Ken Kwapis, Kevin Reynolds, and Phil Joanou, Magnoli realized he was in select company at the school. “Working with your peers and the professors in an environment that constantly challenged your ideas and abilities was exhilarating,” said Magnoli, “like stepping across a high-wire spanning a canyon with just a pole in your hand for balance. We used to say that if we could make it through film school, then we would have the basic tools to navigate the shark-infested waters of Hollywood.”

With others from the same period at USC eventually entering the industry, including Ken Kwapis, Kevin Reynolds, and Phil Joanou, Magnoli realized he was in select company at the school. “Working with your peers and the professors in an environment that constantly challenged your ideas and abilities was exhilarating,” said Magnoli, “like stepping across a high-wire spanning a canyon with just a pole in your hand for balance. We used to say that if we could make it through film school, then we would have the basic tools to navigate the shark-infested waters of Hollywood.”

As a young and aspiring director, Magnoli knew he would need to receive the same type of tutelage as students from areas such as Beverly Hills whom he knew had much deeper pockets than himself. ”I entered USC as a graduate student in spring 1976,” he reflected. “I graduated and drove to California in 1974 to establish residency. USC was the only school I applied to. I figured out what NYU was about, Chicago was about, UCLA and USC. I didn’t want to stay on the East Coast. Martin Scorsese had just made his mark, and East Coast schools were very anti-Hollywood. I didn’t want to go through that. Chicago didn’t interest me, because I didn’t see anyone who graduated there who was getting into the business. I realized that I didn’t have any cash I could burn.”

Soon after his acceptance into film school, Magnoli would realize just how competitive the landscape at USC would be. “The graduate cinema school was no different from the regular program – we shared the same environment,” he stated. “You were still interacting with each other. It’s just that you entered the school at a different level. Most of us came in with different degrees – we were put into the same pool. There were only two or three years between us. Once you were taking [cinema course numbers] 140, 290, 310, 480, 580, you were taking classes with everybody. You noticed a difference right away — those who had a degree had the ability to articulate themselves more so than others. We were in course 290 where everybody makes their mark. The very first day, there were 90 of us accepted out of 5,000 applicants.”

The program mercilessly separated the strong from the weak, and Magnoli soon learned that his program size would be cut down considerably, putting the onus on his shoulders to perform at his highest level. “The production faculty was standing in front of us and said, ‘Here’s the scoop – there’s 90 of you in the graduate school; there will be 45 of you left after the first semester,’” Magnoli recalled. “’Then 20 left. When you graduate, there will be 10. We will not let you proceed if you have no talent.’ They had 90 students who were at the top of their game in whatever major they majored in. You had to write why you should be a cinema student. They heavily weighted what you wrote in that regard. They didn’t want to see any portfolios. We were all equal and in the same boat. It was scary. You had to make five Super-8 films and the first one had to be five minutes long of a person, place or thing.”

The program mercilessly separated the strong from the weak, and Magnoli soon learned that his program size would be cut down considerably, putting the onus on his shoulders to perform at his highest level. “The production faculty was standing in front of us and said, ‘Here’s the scoop – there’s 90 of you in the graduate school; there will be 45 of you left after the first semester,’” Magnoli recalled. “’Then 20 left. When you graduate, there will be 10. We will not let you proceed if you have no talent.’ They had 90 students who were at the top of their game in whatever major they majored in. You had to write why you should be a cinema student. They heavily weighted what you wrote in that regard. They didn’t want to see any portfolios. We were all equal and in the same boat. It was scary. You had to make five Super-8 films and the first one had to be five minutes long of a person, place or thing.”

After making it through the cuts early on, Magnoli geared himself up for the creative challenges lying ahead. “We did courses 310, then 480 and after all that I edited two films that James Foley directed – a 480 and a 580,” he said. “I decided to make a thesis film. With a thesis film, you have to pay for your film stock, and they’ll give you the equipment. I took out a loan for $7,000 and made the film over the summer. You are using student crews and they are getting credit for their classes. But when you do a thesis film, you are the only one with credit – the crew is just helping you out.”

With aforementioned notables plus others such as George Lucas and Robert Zemeckis having made successful 480s, Magnoli knew a thesis film would be his calling card for the industry – and so he created a music-oriented film called Jazz. “I made friends with camera rental places in Hollywood,” he stated. “They would give me a good rate because I was a student. It took me the entire summer to shoot the film on weekends, because during the week, my fellow students were in class. It took me about six weekends to make Jazz. I went into the editing room at USC and cut it. May and June I shot it, and edited till the end of August.”

Having experienced early success, Magnoli would begin to explore new ideas and challenge norms in Jazz. Enlisting colleagues from his film school to aid him in his endeavors, Magnoli experimented with various methods of combining music with film. “The initial idea was I wanted to do a film that would raise the bar for how to use music in a motion picture,” he said of Jazz. “I played drums all the way until 12th grade. I wanted to work with real jazz musicians. I had the tracks laid, and I was shooting in real nightclubs in Inglewood from 6 a.m. until 3 p.m. when the nightclub was closed. All of the reaction shots were shot at USC.”

Having experienced early success, Magnoli would begin to explore new ideas and challenge norms in Jazz. Enlisting colleagues from his film school to aid him in his endeavors, Magnoli experimented with various methods of combining music with film. “The initial idea was I wanted to do a film that would raise the bar for how to use music in a motion picture,” he said of Jazz. “I played drums all the way until 12th grade. I wanted to work with real jazz musicians. I had the tracks laid, and I was shooting in real nightclubs in Inglewood from 6 a.m. until 3 p.m. when the nightclub was closed. All of the reaction shots were shot at USC.”

As Magnoli discovered his creative identity as a director, the foundation for his future artistic endeavors began to materialize. “That was all the foundation that was being formed for Purple Rain,” he explained. “What I was doing at that time at USC were all stepping stones that led to Purple Rain. When I said I wanted something that raised the bar on a USC production, it was music and film. We were never taught how to do that. My Jazz sound guy David Wild got a Focus Award for best sound and the school benefited from the experience.”

With his directorial ambitions firmly set in Hollywood, Magnoli, along with Foley and Josh Donen, devised a plan for the trio’s work to receive more exposure. “I was there with James Foley and Josh Donen, Stanley Donen’s son, at USC,” he stated. “We hatched this plan. USC never pushed their students into actually getting work in Hollywood. For the most part, these were few and far between. One of the reasons is USC refused to create a mechanism by which the industry could see student work. Our objective is to get an agent to sign us. I screened it at the Norris Theater. I had over 500 people in there. I invited all of the agents in town. I brought in a few other films that I really liked as well. There was an intermission, and I sat there and let the agents fight over me!”

“The Gersh Agency signed me. We had created a marker and got the marker to pay off.”

“The Gersh Agency signed me. We had created a marker and got the marker to pay off.”

Having set the marker and achieving their goal of garnering the interest of industry-leading agencies, Magnoli and his cohorts knew that the change they had affected in USC’s film landscape was the key that opened the door. “We were the beginning of that,” he said. “We were literally the vanguard. Now it’s normal. As they became more and more successful, USC realized that screenings of student films could be an event, and now these industry screenings take place at the DGA with a lot of publicity. People were getting signed based on these screenings. I was excited, but it was part of the master plan.”

Magnoli’s Jazz eventually won a student Academy Award, and he soon after its release, he edited Foley’s feature film Reckless for MGM leading to a fortuitous conflagration of events for the filmmakers. “During postproduction, Reckless’ producers wanted to see the movie,” he said. “Rob Cavallo, Prince’s manager, and I had a discussion, and that led to me doing Purple Rain.”

Prior to agreeing to direct Purple Rain, Magnoli saw first-hand that getting the industry to accept Cavallo’s script was going nowhere. “Cavallo came to watch Reckless and asked if Jamie [Foley] would be interested in doing a movie with Prince,” Magnoli remarked. “I said, ‘Absolutely.’ I got on the phone with Jamie in New York, and said ‘We’ve got our next picture with Prince – you’ll direct and I’ll edit.’ Jamie got the script and read it right away. He said, ‘It will not fly. Thank the guy, but I pass.’ I felt really bad. We’ll figure something else to do together. I had to discuss it with Cavallo. The next day the phone rings. I was in the editing room on Reckless. I knew immediately it was Cavallo on the phone. He said, ‘I did some checking up on you, and you made this film Jazz and have a deal with Paramount.”

Though Magnoli disliked the dark tones of Cavallo’s script, the budding director found an unlikely opportunity to re-tell the story himself. At a followup meeting with Cavallo, Magnoli virtually improvised an impromptu pitch which would later become the film we now know as Purple Rain. “I explained to him that the best way to create something unique is to hire a writer-director who could go to Minneapolis and saturate himself in Prince and the band then write something authentic and from the heart based on that experience,” Magnoli noted. “He said to me, ‘What would the story be?’ I launched into a pitch totally off the cuff that lasted seven minutes which was the skeleton of Purple Rain. It was because I was editing so much, I could see it as an editor – the whole story. I started layering all this stuff. In that excitement, I saw the story, coming up with a shot list right on the spot, a three-act structure. Cavallo was freaked out but was sold on the spot. He got it. Cavallo said, ‘You just told me a great story; what are you going to do about it?’ He was challenging me.”

Though Magnoli disliked the dark tones of Cavallo’s script, the budding director found an unlikely opportunity to re-tell the story himself. At a followup meeting with Cavallo, Magnoli virtually improvised an impromptu pitch which would later become the film we now know as Purple Rain. “I explained to him that the best way to create something unique is to hire a writer-director who could go to Minneapolis and saturate himself in Prince and the band then write something authentic and from the heart based on that experience,” Magnoli noted. “He said to me, ‘What would the story be?’ I launched into a pitch totally off the cuff that lasted seven minutes which was the skeleton of Purple Rain. It was because I was editing so much, I could see it as an editor – the whole story. I started layering all this stuff. In that excitement, I saw the story, coming up with a shot list right on the spot, a three-act structure. Cavallo was freaked out but was sold on the spot. He got it. Cavallo said, ‘You just told me a great story; what are you going to do about it?’ He was challenging me.”

With Cavallo immediately sold on Magnoli’s three-act story, there was one final necessity: selling Prince himself on the story. “(I told Cavallo), ‘I’m going to take the weekend off; you’re going to put me on a plane,” Magnoli detailed. “’If he likes it, we’ll make a movie. If not, send me back home.’ The next night, I was on my way to the airport. I met Prince that night and said, ‘Here’s what I want to do.’ His reaction was, ‘You know me? How is it that in 10 minutes you tell me my life story?’ I said ‘If you are willing to embrace what we are doing here and let your father smack you in the mouth in the first five minutes, we’ll make a movie.’ I said, ‘In this time and age, there is no one who doesn’t want to take a crack at a rock star.’ We had to be authentic. That’s where I was.”

According to Magnoli, Prince was able to provide a large catalog of songs, which allowed flexibility in the song-selection process and helped form Magnoli’s screenplay. “When Prince and I got together,” Magnoli recollected, “he said, ‘I have 100 songs that I think would work for the movie.’ I went through all 100 fully-produced songs. I asked for a lyric sheet for each song, listened to the song, and as I was writing the screenplay, I would craft the songs into the narrative. One of the things that was important to me was not to ‘insert the song’ that had nothing to do with the story. In that context, it’s fantastic, but the idea that you just break into song and there’s magically an instrument in the scene, I knew wouldn’t work.”

According to Magnoli, Prince was able to provide a large catalog of songs, which allowed flexibility in the song-selection process and helped form Magnoli’s screenplay. “When Prince and I got together,” Magnoli recollected, “he said, ‘I have 100 songs that I think would work for the movie.’ I went through all 100 fully-produced songs. I asked for a lyric sheet for each song, listened to the song, and as I was writing the screenplay, I would craft the songs into the narrative. One of the things that was important to me was not to ‘insert the song’ that had nothing to do with the story. In that context, it’s fantastic, but the idea that you just break into song and there’s magically an instrument in the scene, I knew wouldn’t work.”

In creating the template for Purple Rain, Magnoli had proven source material as his guide. “What worked for me was the film Cabaret by Bob Fosse,” Magnoli commented. “The fact is that the musical moments broadened the scope of the narrative, and the narrative drove the musical moment. It was a seamless flow of narrative and music. On top of that, the lyrical content of each performance number illuminated what was said in dialogue before and after the song. That was my approach – onstage and offstage. The narrative had to reflect and amplify the musical number and the music had to thrust me back into narrative. I wrote the screenplay and named the song that would play at that certain place.”

With a lack of MTV-era media to influence the film, Magnoli drew from his own experiences to create the movie’s visual world. “This was pre-MTV. There was no visual archive that we are now saturated with. There were no rock ‘n’ roll movies that were concert oriented. Basically, I knew what a nightclub should look like because I was a drummer in bands and was in a lot of clubs. I knew how clubs looked and what they smelled like. I was always fascinated by waitresses trying to get through a crowd of people with a tray full of drinks. In Jazz, I did the same thing: it was about creating images. I never watched MTV. By the time the film came out, MTV exploded. The film was already shot. There was no learning curve based on MTV at all.”

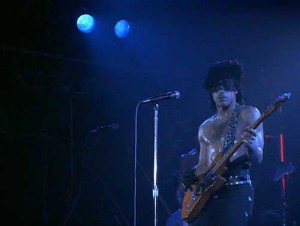

While the shoot went fairly smoothly, Magnoli notes the cooperation between departments as a key factor in the shoot’s effortless fluidity. “It was about as effortless as you can imagine,” he said. “The experience of creating an environment for the artists to work in was magic. The film crew was coming into a musical component that was fully formed. These musicians are used to performing and getting around on their own. They were highly suspicious of outsiders. Our job was to bring their art to a visual medium and meld into the background and do our work and bring them to the level we need.”

While the shoot went fairly smoothly, Magnoli notes the cooperation between departments as a key factor in the shoot’s effortless fluidity. “It was about as effortless as you can imagine,” he said. “The experience of creating an environment for the artists to work in was magic. The film crew was coming into a musical component that was fully formed. These musicians are used to performing and getting around on their own. They were highly suspicious of outsiders. Our job was to bring their art to a visual medium and meld into the background and do our work and bring them to the level we need.”

Sometimes the work of great editing rests more on the isolation of ideas than it does on collaboration. As such, Magnoli had a specific vision, and took it upon himself to create the narrative he wanted. “You never know anything when you are shooting,” he said. “There wasn’t much editing going on on location. Ken Robinson from USC was chopping away. I said to Ken, ‘Just read the script, shape it, but I’m not going to come into this room ever again. I am going to concentrate on getting the material ready to go. Once I get to L.A., I‘m going to sit down and go to town.’ I was inspired by the last minutes of The Godfather. The opening of Purple Rain — the equivalent of Michael Coreleone baptizing his child — is Prince on stage, and the cutaways are about all of the characters as they travel to the club. In seven-and-a-half minutes, I had created these characters and gotten them to the club. Everybody challenged it. Nobody understood what was there until I cut it. “

While the 1980s wasn’t an era known for multi-picture deals, Magnoli was still capable of rolling Purple Rain‘s success into another classic production. “If you had done Purple Rain now, it would almost be like everybody in town would be trying to give you a 10-picture deal,” he said. “Back then, there was an attitude like, ‘It’s okay.’ There was tremendous response, but it wasn’t like someone came to you with a gift. There was a moment where Warner Bros. wanted me to stay. They handed me a script that said Batman. In 1984, the word Batman on a script was influenced by the TV show. In fact, the last scene Batman was carrying an oversize pencil fighting the Joker who had an oversized eraser. I didn’t find its campiness appealing on any level.”

Nonetheless, Magnoli stayed in the Batman game at the time – to a point. “I am talking to the same people I made Purple Rain with,” he noted. “’It should be dark, incredibly frightening, and examine the psychological underpinnings of this.’ They just wanted to make a campy movie. Two years later, the comic book writers of Batman decided to reboot the franchise with The Dark Knight. They knew that they had to become more serious and darker. By 1988, Tim Burton was handed the dark version. By then, I’m managing Prince and I’m in a meeting with Tim Burton for the music on Batman — we did the Batman album. I wanted to do very specific things filmwise and musically. Prince wasn’t interested in spending the time. He ended up making Graffiti Bridge, so it was better for us to split.”

Over three decades into his career, a wiser and more adept Magnoli still believes that the major studios have yet to fully maximize the potential at their disposal. Now more than ever, he believes in the immense potential of allowing creative talents to shine through and break into the ranks such as he did so many years ago. “It was obvious that they still didn’t understand how it got done,” he said of Purple Rain’s immense musical-film crossover success. “It was strange. Eight Mile and La Bamba and Selena; in 30 years, they’ve made four films. It’s a very difficult thing. Most people don’t see it translating into something. There were offers, but now you need to learn how to negotiate this thing called Hollywood. I’ve figured it out, and I’m trying to get an entire slate financed. There are 13 scripts plus a television show. The internet now allows you to be anywhere on the planet.”