If you’ve been a fan of Edgar Wright’s movies for a long time, you’re likely to have, at one point or another, marveled at some of the locations he’s captured on film. Wright’s most recent film, Last Night in Soho, is no exception, as it follows Thomasin McKenzie’s Eloise from her first experiences as a student in London’s Soho district to a dream scenario where she seemingly travels back in time to connect with Anya Taylor-Joy’s Soho showgirl, Sandie. It’s a movie that not only captures the present-day Soho but also fantasizes about the ‘60s Soho that Wright must have seen in many of his favorite British thrillers from the time.

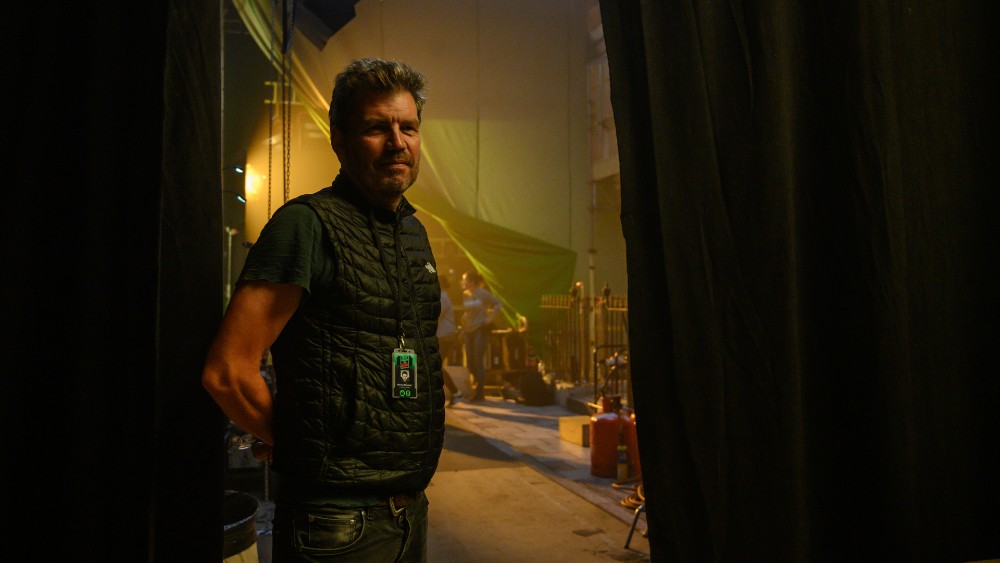

Wright’s right-hand man in all things is Production Designer Marcus Rowland, who has performed that role in all of Wright’s movies going back to Shaun of the Dead in 2004, but has also traveled “across the pond” to make films with Wright in Toronto (Scott Pilgrim vs. the World) and Atlanta (Baby Driver).

For Last Night in Soho, Rowland and his art department not only had to find believable locations to represent modern-day Soho, but also had to build a lot of nightclubs and streets for the ‘60s Soho, with help from the visual effects, but with no help from a pandemic that decided to strike mid-shoot, shutting down production. (Rowland also did Production Design on Dexter Fletcher’s amazing Rocketman, which also involved recreating a lot of different venues and time periods.)

Below the Line spoke to Rowland back in October, but in the interest of protecting the film’s many spoilers and twists, we held this interview back until more people had a chance to see the movie. Because Rowland had worked with Wright for so long, we just had to ask him about one of the myths surrounding his earlier film, Hot Fuzz, but we also touched upon many of Wright’s other films.

Below the Line: I’ve spoken to Edgar a lot over the years about all his different movies. I was surprised to learn that you did production design on all his movies, as well as Joe Cornish’s two movies.

Marcus Rowland: It just sort of happened, really. It’s a small group of us with Nira [Park], Edgar’s producer, and James Biddle. We’re a small group of guys who know each other very well.

BTL: I’m glad to see that he’s used a lot of the same people over the course of his career. There’s the oft-used cliché about having a shorthand, but obviously, it’s true.

Rowland: Yeah, of course, it makes a massive difference, really, when you actually understand people’s workings and the type of things that are appealing to Edgar. We understand each other, and I fill in the bits that he… the shorthand makes quite a lot of difference.

BTL: I want to go back a bit, since Shaun of the Dead was also your first film as a production designer. Were you working in the art department for other films or television before that?

Rowland: Not really. I went to art college, did the usual sort of route, then sort of fell into doing music videos, some TV, very early on TV comedy, which I did with Nira, Edgar’s producer — we both started at the same time. So we go back even further than Edgar. That goes back like 30 years from when we were in our early 20s. I was doing commercials for quite a long time for my sins. And then obviously, I’d done Spaced, and I’d done a couple of other things with Edgar, so when the opportunity came… it’s like everything. You always want to get into film — it was just the perfect opportunity.

BTL: Did you go to school specifically for set or production design?

Rowland: No, I sort of trained as an illustrator, really, which was useful. I sort of did a bit of everything. When you speak to young kids who are thinking of doing film, I just sort of say I was completely unplanned. It was by chance that I sort of fell into it, and then discovered something that I enjoyed in the process. I enjoy, not just the design side of it, but I actually really enjoy building and constructing things, as well. But it wasn’t premeditated. It was purely by chance. I sort of grasped it, really.

BTL: As I’ve been talking to more production designers and people from different departments, I don’t think a lot of movie lovers realize when they’re watching a scene in a movie, it’s not just the director and cinematographer involved in making it look so good.

Rowland: No, totally, and if they do, I don’t think they quite understand the role either. Obviously, like film, it’s very sort of ambiguous. People do every role completely differently, or they take more of one bit of it. Certainly, it’s much more of an overall visual content rather than just the set design and that part of it, it’s the whole process of the whole look of the film as you go along — locations, props, choosing the shots before you meet with the DP or before they’ve even started. I usually start before, so we’ve usually hit the ground quite running and have a good idea of how we want to take it in the process, especially with Edgar. I spend a bit more time wandering around with him, looking at locations, talking about it, probably before anybody else turns up

BTL: Since you’ve worked with him for so long, is he talking to you even before he’s writing, even if it’s just the general idea or premise. I know Krysty [Wilson-Cairns] and he spent a lot of time writing, but is he talking to you about places in Soho to shoot?

Rowland: This project, Last Night in Soho, had been around for a while. He’s got some other ones going. We always talk about it sort of when it’s about to go really. When it firms up, and that’s the next project, we obviously spend a bit of time talking about how to achieve it, and just walking around early in the morning and looking at stuff. That sort of informs the decisions you make as you go along. We did it on Last Night in Soho, Baby Driver…. Me and Edgar literally… ‘cause we were sort of castaways in Atlanta for a lot of weekends. Especially the American crew were based out of LA. They’d get on planes on a Friday afternoon and they’re gone. We just wandered around trying to piece together the chase sequences and things like that. That’s the sort of methodology that applies through all the films really. The advantage of setting a film based in the right area, like Soho, is that you can explore it. There’s obviously things you have to make work based around the script, but when they’re there, it’s about choosing the bits you want. It’s trying to ground it in the reality, albeit slightly a stylized one, but there is always a logic underneath the choices in Edgar’s world, script-wise.

BTL: Production design is also a tough craft to write about without having pictures to illustrate what a designer is talking about, which is why the art department creates lookbooks and things like that.

Rowland: I suppose the simplest thing people say is that you’re designing sets. I always think it’s never just that, really. That’s sort of the fun, but in the end, whatever you design as a set, it’s only as good as what appears on screen. So really, it’s not just about walking onto a set, and everybody really loving it — it’s about the best way to film it. I think that’s the lesson in the process that you go through with understanding film, as opposed to just designing a beautiful space, is trying to concentrate on the areas that are going to be most striking and the bits that are used most. I think that’s an important part of being a production designer.

BTL: This movie is particularly interesting, because you designed the three movies he did with Simon Pegg, which were rather rural-based films, and then you went to other places like Toronto and Atlanta, but Last Night in Soho is really so close to his home. So let’s talk about Soho. Obviously, Edgar has this modern-day Soho he knows from living there and the ’60s Soho he knows more from movies. I actually rewatched Peeping Tom last night, which Edgar programmed at the Alamo, and I was really paying attention to the locations and how they were shot.

Rowland: You know that the basic roots of [the movie] is two things: the enjoyment of being in and around the present-day Soho from over the last 10 years or so, and then the one that is in films really. That’s certainly one of the starting points of that ’60s sort of approach to the style and look of the film where we’re exploring different… I think the point is that Edgar was trying to explore a different genre — it’s trying to do something different. It was often a combination of different things melded together to highlight the other. Obviously, the intention was to do the real Soho against the sort of period glossy version, and they both set each other off really. Certainly, the more contemporary version highlights the decadence of the’ 60s version. It’s a place we both know very well, and often take for granted, because you’re just wandering through it.

It was always a fun idea to try and film in Soho, which is crazily busy nowadays. When we were filming, there wasn’t COVID, it was full-on sort of busy, jostling Soho and just dressing those streets. We just tried to work out which bits we could control and then dress quite a lot. It was fun, because even though we know it well, once you start spending time there and when we’re dressing the streets, people come up. Albeit it’s a quieter place to go out now, but there are a lot of people who still live there, so they come up to you. There’s still people who work in the film industry. There’s still people who have lived there all their lives, so you get that interesting sort of exposure. The real world of Soho, that’s still there, there’s still a seedy side to it, thank God, and it’s not all sanitized. It still has a character.

BTL: When I spoke to VFX Supe Tom Proctor (Note: an interview coming soon), he told me about how they used visual effects to recreate London of the ’60s, adding cars, etc. But he also mentioned that when you came back from lockdown, you did end up building a lot more stuff on stage even though presumably there would be fewer people on the streets, which should have made it easier to shoot on locations.

Rowland: I mean, basically, apart from the end sequence, which is all the moving stills really, we couldn’t get permission to film in Soho anymore. It was fantastically quiet, and you could wander around and go anywhere, and there wasn’t anybody around. It was uniquely abandoned in a way, but the authorities wouldn’t let you film there. So we ended up building a replica of the Toucan again, and when the Shadowmen are in the ’60s alleyway when Eloise is chasing Sandy down the alleyway both with white coats, we ended up building a large chunk of that, which is obviously augmented with digital help at either end of the shot. We ended up building at Pinewood, and it’s sort of a funny business, because in the process, we probably would have built the Toucan in the first place if we had the money, the exterior. As it transpired, there was no option so we ended up building, which is good. The basement in the Toucan is a build as well. There’s quite a few bits that I hope people wouldn’t know that they’re builds.

BTL: I had trouble figuring it out, especially since I knew that the shut down affected the shoot and then you had to come back, and I had no idea what was shot before or afterward either.

Rowland: There are chunks of that, there are bits of warehouse stuff. There are bits all the way through that we sort of tried to… It’s the usual. We’re trying to make it seamlessly blend in, but The Toucan is a bar I’ve drunk in quite a lot. It is possibly the smallest place, I mean it’s very small, ridiculously small. You wouldn’t, in any logic, choose to shoot [in it]. So the downstairs we built, because there was no tie-in, but there’s a quite a lot of action with the entrance of the real [Toucan], so initially, we did shoot there, and you could barely get ten extras in and the camera. There’s no way that we wouldn’t have shot in part of it. The whole flavor of Soho was to try, and obviously if you look at it from a production point of view and costing, usually the first thing to go is, “You can’t film there. It’s much better, we’ll recreate it somewhere else, or we’ll find another street”, and that was definitely not the intention. It was always to be true to Soho, so as much as possible, and until we didn’t, we shot in Soho, because that was about the character of the place.

BTL: At least you shot at Pinewood and Ealing, so you were still in England vs. going to Romania or somewhere else because they were not hit as hard by COVID.

Rowland: No, we don’t tend to do that. I don’t know whether you’ve ever been to Romania. I’ve only ever been when I’m working, and it’s quite tough. Yeah, so we were in Ealing, Leavesden Studios, all the clubs, the ’60s clips, the Rialto, the Café de Paris, and the sort of seedy basement club were all built in one of the oldest stages or really old aircraft hangars, that were at Leavesden Studios, which is Warner Brothers. We had them all lined up in a row, so we had finished them pretty quickly, and we went from one to the other. As a designer, it was always a great buzz when you’ve gone through the process of designing, and you get to a point where you feel that it’s all coming together, and it’s going to come together well, and it’s going to come together at the right time. Walking into a space where you’ve got all these things that you’ve created is a big, big buzz.

BTL: I want to ask more about the clubs. I actually went to the set of Scott Pilgrim, so I got to see one of the places where Scott’s band battles others, including the giant warehouse space where his band battles the twins. And I saw a little bit of Gideon’s club from the end. For Last Night in Soho, we see two clubs from the 60s, the Rialto and the Café de Paris – an amazing sequence there – but I’m curious about the two spaces and the Inferno where Ellie attends a Halloween party. Were these real clubs or were they all built?

Rowland: The Café de Paris is definitely a build. The Rialto, which is the one where she’s the puppet on the string stage is a build. The exterior is a build on both within a location, and then the other basement club, the psychedelic club, is a build. Where she sees the Shadowmen in the Halloween club is actually a real club, but the exterior is another club, just to confuse clubgoers. The interior club is called the Inferno, but the exterior one is called something else — can’t remember what — so people will get very confused.

BTL: I remember that one of the clubs in Scott Pilgrim you recreated but was actually a real major Toronto club.

Rowland: It’s always been the case that at that time, practically you can’t take a [gun?] to a club, so it’s easier to build them as such, so you’ve got a choice of your scheduling, but we always stylized and make them different. All the club interiors and probably about 80% of that film is all build. I mean, it’s all stylized. I mean The Rocket, if I remember rightly, that was build, Lee’s Palace was build, and then obviously, the one you’re mentioning was build, Gideon’s base. The one that the Katenagi Twins, where they’re playing, that one was partly carved out of an existing space, we just reduced the scale of it. Actually, at that point in time, we took over most of the actual functioning stages in Toronto to accommodate all these pieces of clubs. They’re loosely based on the real club. I mean, we obviously visited them. but they’re much more stylized, siphoned-down, recused all the clutter, and just trying to get the essence of the place.

I think that’s the same with a lot of Rocketman. You have the Troubador, and a lot of people go, “Oh, that’s exactly like the Troubador!” It was never exactly like the Troubador. We just took some of it and stylized it in the same with Café de Paris. It’s got the essence, but we’ve amped up the style, we’ve created another level, the scale’s bigger, more sumptuous. The layout is roughly the same, but that’s the fun of doing it. if you were doing a complete replica, it sort of wouldn’t be worth doing.

BTL: Was there a real two-story house where Ellie stays while in London, or was that all built in terms of upstairs and downstairs on separate stages?

Rowland: There’s obviously the exterior street, which is actually not in Soho, but it’s just the other side of Oxford Street, which is just off Charlotte Street. It’s a really good little mews that, up until recently, was a little bit more rundown. Mrs. Collins’ house is on the street, and then everything else interior-wise is built. All the backstage stuff is built, so basically, we end up building… At one point, we had like three bedrooms really, because we had the Ellie’s version of it, the Sandy’s version, a version attached to the corridor, then a Top Shop version. It becomes multiple pieces of set, and we were in Ealing. I’m not sure you’ve ever been there, but it’s really lovely… I’m filming there at the moment — it’s really small, so we sort of cram all the sets in there, and it’s where we did Shaun of the Dead as well. I did bits of The Kid Who Would Be King. We’ve used it quite a lot, but it’s a really old school sort of more like a New York sort of stage. I’ve been around Silvercup and all those ones. I shot there once. I was always staggered when I wandered around, and they were doing a series, and literally they’ve got everything crammed, four-foot away from the edge of the walls. It’s a bit like that.

BTL: I’m sure you know this, having worked with Edgar for so long, that he has a diehard fanbase, who will automatically go looking for all these places. I’m not sure if the Toucan has already started seeing mobs of people who show up and are disappointed that it’s different.

Rowland: I think the people were fairly thinking about retiring, and certainly, London and the UK is less COVID at the moment than America is, so it’s all pretty open. (Editor’s Note: This interview was done in October) I haven’t been back to the pub. I think it’s probably time to have a trip down there and see what the impact was. I’m sure it will be significant, because every possible location that we’ve shot in from Shaun of the Dead — the street that we staged the house in, even though the interior was somewhere else, and the shop where Simon buys the Cornetto is constantly being visited by fans. It’s a bit of an homage, and it obviously expands their clientele quite significantly.

BTL: Edgar mentioned to me that the Winchester was closed, but that he wanted to burn it down at the end, and just couldn’t make it happen budget-wise.

Rowland: No, that was a stretch that film, as you can imagine. It was 3.4 million at the most, I think, and you burn through it. It was an eight-week shoot. It was extremely tough on everybody, very much on Edgar, and every penny was squeezed out of it, and it was done with a passion, not a financial drive really, so yeah, that was always in the script … but I don’t think I miss it, personally.

BTL: I had asked him if he had $20 million more and could go back and redo or change anything with the more experience he has as a filmmaker, if he would change anything. Maybe in 20 or 30 years, he’ll get the money to just go and build a new Winchester just so he can burn it down and add it as a tag.

Rowland: Obviously, nowadays, post has moved on quite a lot. You could have done a bit more digitally, which we couldn’t afford to. Like the house we burn of Mrs. Collins, there’s practical bits to it, and we build a piece on the backlot to scale of the exteriors, and they take the elements on and paste it in, but we obviously didn’t burn down the location. Even going back 18 years ago, that was available, probably to a very, very big budget but certainly wasn’t available to us. You’d have to have done quite a practical build — you’d have to build something on a backlot. For me, it might be in his mind, but I never questioned it. When we’re burning the pub, they’re behind the bar and the bar’s on fire. I mean, it’s sort of enough. This is how little money we had: the bar was hired, even though it’s on fire (laughs). I’ve covered it with some fire-protective material, which sort of lasts for a little while, but then we’d spent time tiding it up, putting it back. I don’t know. I think it’s part of its story really that you wouldn’t really need it.

BTL: To wrap up., I would like to ask about another movie you did with Edgar, which is one of my favorites, Hot Fuzz. You had just done Shaun of the Dead together, and for his second movie, he brings you to the place where he grew up, so I’m curious what you thought when you realized you’d be shooting most or all of the movie in Wells.

Rowland: No, it wasn’t. The truth is that Simon [Pegg] and Edgar had gone down to Wells to write, and it obviously was where Edgar grew up, and when they were staying in the hotel, having a fun time writing, they sort of based it around the whole center of the town. So all the geography and all the elements that eventually appear in the film are very entrenched in the script. The reality was at the time, initially, Edgar didn’t want to film in his hometown. We spent an awful lot of time with the location manager scouring practically every village south of London, or every town, trying to find somewhere that matched Wells. I mean, literally, it was a weekend trip. I’d go away with him, with the location manager, we’d trundle around, drive down, get out, wander around and go, “On, no, this doesn’t fit with this.” We literally couldn’t find it anywhere.

By that point, I was sort of saying we need to go up north to do it, and eventually as sort of by osmosis, we ended up back there. It was the right thing to do, but it actually wasn’t the first decision. The decision to try and do it somewhere else took ages and ages to work its way through. And then the truth is with that film? Actually, we shot a lot in London. All the hotel interiors, and all those bits that aren’t built, and then some of the pubs and interiors. Because you just get outside M25. It’s the usual that applies to all filming — it’s much more expensive to relocate people further away. As usual, you’re sort of condensed into a much smaller area and the model village was built just in North London, and a lot of the interiors and then some of the exteriors. That hotel they’re in is in North London, but if it works well, and it’s seamless, even I begin to forget which bit was where.

BTL: [Laughs] Hey, it’s a fun romantic story when he’s doing Q and A’s and interviews for the movie.

Rowland: I think he’s forgotten about the torture that went into it. Although I would say it’s like all the decisions that you make in film, some you can make quicker, but to be honest, with every one that we made with Edgar, it’s always agonized… study it, think about it.

BTL: Well, they all came out great, so….

Rowland: That’s why they’ve got this sort of depth, and I think that’s why people generally… like with Baby Driver, most of those chases — not all of them fit together perfectly — but they’re sort of constructed, so you could try and revisit them and you can restructure the journey. It all seems very logical at the end, but at the time of doing it, it’s a big puzzle that you feel you’re never going to solve in terms of like Mrs. Collins’ exterior. We went all around Soho and the peripheral area in Camden, and we slowly whittled it down to the right street. The decision-making process where you actually commit to something is fairly time-consuming and arduous, but once it’s done, you soon forget about all the other choices, and that’s the place, and it’s always been that way, really, with all these decisions.

Last Night in Soho may no longer be in many movie theaters, but it’s available via VOD on many digital platforms, and it will also be available on DVD and Bluray on January 18, 2022. Look for our interview with VFX Supervisor Tom Proctor in the new year, and you can also read our earlier interview with Wright and co-writer Krysty Wilson-Cairns.

All photos courtesy Focus Features, except where noted.