I don’t normally refer to the work of other journalists as “inane,” but I’m not sure how else to describe a piece I read this week in Variety, which basically blamed Netflix for the death of both the mid-budget movie and the original action picture. The fact that someone decided that it was Netflix’s fault that people aren’t leaving their homes anymore to see movies to which they used to flock defies belief, while it ignores the ongoing reality of Hollywood over the course of this century.

The thesis is centered on the lack of success that Michael Bay’s latest film, Ambulance, had at the box office last weekend. It opened to just $8.7 million, a disappointment by any measure, but to blame it on Netflix? Were I to make a list of the reasons why the movie failed, the streaming service might have earned a mention, but not before I’d come up with a whole other bunch of things first.

Let’s start with the obvious: Hollywood killed the mid-budget movie a long time ago. I have complained about this in some form or another for years, both in this space and others. Hollywood has simply stopped making the kinds of movies that made us fall in love with The Movies in the first place. The focus is almost entirely on franchises, intellectual property, or franchises based on intellectual property. When I made my first movie 25 years ago, I initially had a hard time finding a distributor because it was a romantic comedy without big stars in it, and the studios were the only home of rom-coms, all of which featured big stars.

Of course, studios have all but stopped making romantic comedies these days because they aren’t big enough money makers, so the ones we do get are mostly low-wattage indie fare without any big stars. The same goes for the kinds of mid-budget movies that the Variety piece mentions. Naturally, there are exceptions, such as King Richard, which was made and released by Warner Bros. But even though it’s an original film with a medium-sized budget ($50 million), it was based on the early lives of two of the most famous athletes on the planet — Venus and Serena Williams — and fronted by one of the world’s biggest stars, Will Smith, so it might as well be considered intellectual property because audiences were already familiar with the story, making it not much of an exception after all. You could apply the same logic to WB’s upcoming Elvis biopic from Baz Luhrmann.

Those kinds of mid-budget movies used to be the norm. The studio would sprinkle them throughout the year, with many coming out between Labor Day and Christmas. Then, when the Oscar nominations were announced, most people had seen most of the movies and could debate the nominations with those who paid attention to such things.

But gradually, the studios started making fewer movies in order to spend more on the movies they did make, as execs embraced the idea that the size of a film’s budget was directly proportionate to its box office ceiling. Tired of churning out singles and doubles, execs embraced the idea that ‘you’ve got to spend real money to make real money,’ and began swinging for the fences. As a result, instead of putting out 15 or 20, maybe even 25 movies in a year, studios began putting out just a handful, most of which are nine-figure behemoths that could conceivably make a billion dollars but are more likely to do a little bit better than break-even, if that.

If you’re looking for more reasons, I’ve got them. COVID hasn’t done anything good for the theatrical model, as it has trained us all to consume more content at home. Just the other day, in fact, I was talking to a friend about movies and I mentioned that they had to go see The Batman in the theater. “Nah,” he said. “I’ll just wait until it’s on HBO Max in a couple of weeks instead.” I tried to convince him that it needed to be seen on the big screen, and his response was, “Eh, my TV is pretty big.” I imagine there are a lot of people who got used to watching new movies at home and aren’t in any rush to return to theaters, and Hollywood opened the door to that problem.

Now, part of that decision was by necessity due to the pandemic, but the other part is of the industry’s own making, which brings me to the next issue — Hollywood’s shrinking theatrical window. Why should anyone bother to shlep to the theater if you can expect to be able to see a new movie at home in just a few weeks? Universal released Ambulance, and for now, you can only see it in theaters, but after 45 days it’ll be available on Peacock, so unless a movie has that must-see-now factor that Spider-Man: No Way Home had, most audiences are content to wait and maximize their ROI on the streaming services they’re paying good money for each month rather than pay even more money to attend theaters. Ambulance didn’t receive a day-and-date release like Marry Me and Halloween Kills and as a result, it’s being written about like a box office loser, having entered a crowded marketplace that hasn’t had to support this many notable studio releases (Sonic the Hedgehog 2, Morbius, The Lost City, The Batman, Uncharted) in the past two years.

There’s another factor that hurt Ambulance more than Netflix, and that’s its two leads. I happen to be a big fan of both Jake Gyllenhaal and Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, but neither is exactly a movie star. They both star in movies, yes, but the days of the genuine Movie Star who gets people flocking to the theaters has dwindled to the point where I think there is only one left.

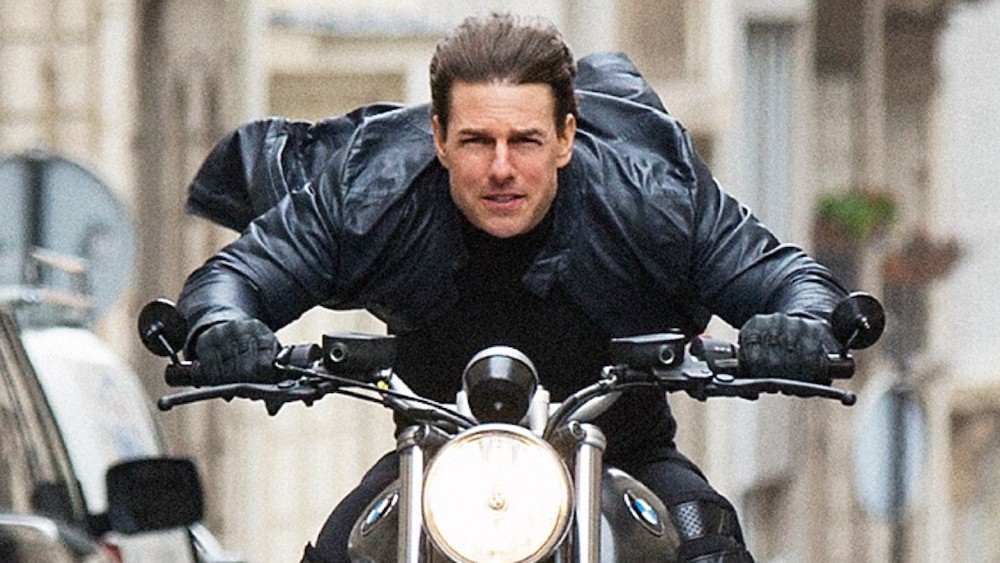

Tom Cruise is the only actor in Hollywood with the power to take on a studio and actually win. He’s holding Mission: Impossible 7 hostage and won’t finish it unless and until Paramount agrees to give the movie a proper 90-day theatrical window before it ends up on the studio’s in-house streaming service, Paramount+. Even as he shoots Mission: Impossible 8, he’s battling it out with the Mountain, and my money’s on him. I’d challenge you to name another actor in Hollywood with that kind of clout, but it would be a waste of time. You can’t. That person doesn’t exist.

Gyllenhaal and Abdul-Mateen are both great actors but neither one puts butts in seats like Cruise, so that’s another reason why Ambulance crashed at the box office last weekend. To blame Netflix for its performance — or the cumulative performance of mid-budget movies of late — is sort of like saying the reason you’re no longer with your ex is because of the guy who started seeing her long after you broke up. In fact, it’s Netflix that is filling the void left by the studios and making those midrange movies, giving people the chance to see them.

Ironically, other streamers are starting to do this now, having become the preferred distribution method for the kinds of mid-budget movies that studios used to release directly in theaters. When studios do occasionally release a mid-budget movie in theaters and it doesn’t perform as well as they’d hoped, the media takeaway is ‘well, that movie should’ve gone day-and-date or premiered as a streaming exclusive.’ This isn’t always true — sometimes we should commend studios for taking a swing — but in the case of Ambulance, that movie probably would’ve had more of an impact in terms of pop culture had it been available this past weekend on Peacock.

It seems to me that the answer to this problem is pretty simple: Studios can either embrace the streaming model that appears to be the easiest path to financial success and continue to limit theatrical releases to VFX-driven tentpoles, or they can do the hard work to retrain audiences to come back to movie theaters, even if superheroes or wizards aren’t involved. They may need to take a few losses in the immediate future, but the long-term reward could be significant.

If they aren’t willing to stomach those losses then studios should stop complaining because they brought this on themselves. They can either fix the problem or embrace the new normal because there is no longer anything in between.

Neil Turitz is a journalist, essayist, author, and filmmaker who has worked in and written about Hollywood for nearly 25 years, though he has never lived there. These days, he splits his time between New York City and the Berkshires. He’s not on Twitter, but you can find him on Instagram @6wordreviews.

Neil Turitz is a journalist, essayist, author, and filmmaker who has worked in and written about Hollywood for nearly 25 years, though he has never lived there. These days, he splits his time between New York City and the Berkshires. He’s not on Twitter, but you can find him on Instagram @6wordreviews.

You can read a new installation of The Accidental Turitz every Wednesday, and all previous columns can be found here.