Many movie critics have talked of the high-quality and diversity of this year’s Oscar nominees for best motion picture, that may in the future be ranked with the storied contenders of 1939, which included Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz. This year’s five best cinematography nominees, along with others who did notable work but did not make the final cut, have also produced film imagery that ranks with the best of the past.

Moreover, with digital cinematography making rapid inroads at the same time directors of photography still have the choice of working with film, for now at least, a best-of-both-worlds situation exists in terms of the choices and tools available to DPs. And this year’s Academy Award nominees run the gamut from DP Phedon Papamichael’s reprise of traditional black-and-white on Nebraska, to Emmanuel Lubezki’s cutting-edge work on Gravity, which required the development of new virtual cinematography techniques. Here is a look at the five nominees and their remarkable work:

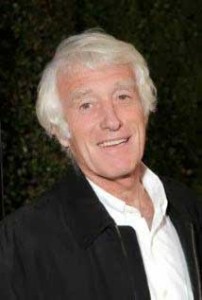

In his cinematography for Prisoners, a dark and disturbing mystery about child abduction and the line between coercion and revenge, director of photography Roger Deakins, working for the first time with Canadian director Denis Villeneuve of Incendies fame, chose to go with a realistic and restrained style to keep the film from tipping into melodrama. “We basically went by the ‘less-is-more’ philosophy, moving the camera only to increase tension, and lighting the film in a stark naturalistic way,” said the DP. “We wanted to hold shots for a long time and force the audience to confront the reality of what it means to take the law into your own hands – what does it really mean to torture a man?”

Deakins is known for his sophisticated lighting and use of practical sources of illumination, such as table lamps in home interiors or houses decorated with Christmas lights in a night scene, subtly augmented by professional film lights. “I did use a lot of practicals,” noted the DP, “but many had to be added or created.” For the many night sequences “I had to design exactly what I needed in every scene as there was nothing there to start with.”

He comes from a documentary background. “I still love being hands on, being totally involved, operating the camera and moving the lights myself,” the DP noted.” Deakins shot with an ARRI Alexa digital camera, especially handy for dealing with the many lowlight situations. He used the same camera last year for Skyfall, the latest James Bond flick, which also got him an Oscar nomination.

In all he has received 11 Academy Award noms for best cinematography, though he has yet to win one. His others have been for films including cult favorite The Shawshank Redemption, and for several of the many movies he lensed for the Coen Brothers such as The Man Who Wasn’t There, No Country for Old Men and True Grit. He was the recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society of Cinematographers in 2011 and for three best feature film honors for the ASC.

Inside Llewyn Davis, Bruno Delbonnel

Inside Llewyn Davis, directed and written by the Coen Brothers, is about the Greenwich Village folk music scene at the beginning of the 1960s. But though it is about a specific time and period, director of photography Bruno Delbonnel did not try to recreate a historical look, but rather a mood that reflects the story of its main character, who though good natured is largely a loser of his own making.

“I went for the mood of the script more than recreating any specific period look,” the French DP noted. “First I’m a Parisian, not a New Yorker, so I don’t know what New York was like in the ’60s. What I tried to do was follow an idea, which was the mood of the movie which is about sadness. It was not 1961 New York City. It was New York in winter and a very sad story.”

Looking for some visual inspiration Delbonnel came upon the cover of “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan” album from around that time, showing him with a girlfriend walking down a snow-covered street in lower Manhattan that encapsulated what DP was searching for. “You can feel the slushy, cold New York winter in that photo,” noted the cinematographer. “The main thing was to avoid being too pretty.”

The film has a desaturated color scheme, with an absence of much light or bright colors. It’s often overcast, and because of the season, there’s rarely bright sunlight. And interiors are minimally lit: for example the dark Gaslight Café, an iconic Village venue at the time, where most of the folk performances take place.

Delbonnel saw the overall arc of the film as a kind of folk song. “If you listen to folk songs usually they are very sad. They’re about hope but a hope that doesn’t lead to anything,” he observed. “I also thought of Llewyn’s story as a folk song and I thought it could be interesting to ‘build’ the light as kind of a folk song as well.” The movie was shot on an Arricam camera using Kodak negative film stock, both favorite tools of Delbonnel.

Delbonnel’s Oscar nomination is his fourth. He was previously nominated for an Academy Award for best cinematography for Amelie (2002), A Very Long Engagement (2005) and Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2010).

The Grandmaster, Philippe Le Sourd

When celebrated Hong Kong director Wong Kar Wai first approached Oscar-nominated cinematographer Philippe Le Sourd some years ago, he said he wanted to do a documentary on martial arts that would take about six months to film on location in China. That seemingly modest project evolved into The Grandmaster, a fictionalized period epic about Ip Man, a real life kung fu legend. And it wound up taking the French director of photography three years to lens. The end result of Le Sourd’s arduous efforts is a lush and atmospheric panorama highlighted by a series of intricately choreographed fight sequences that rank with the best ever filmed.

Not only was the shoot a marathon – it lasted nearly 300 days with frequent seven-day weeks and 15-hour days – it posed peculiar challenges to the DP. “There was no advance screenplay to work with when we went to China and every day was a new discovery as Wong Kar Wai would bring a new page of script to the set,” he recalled.

Individual segments took months to film, such as a stylized and erotic fight at a train station between the film’s male and female stars, played by Tony Leung and Zhang Ziyi. Sometimes the director even asked to reshoot scenes several years after they were initially filmed. So Le Sourd was faced with the difficult task of keeping the look consistent throughout. “You no longer light a scene shot in 2009 the way you do it in 2012,” he said. “The faces of the actors change, and you change personally over such a long period of time.”

In addition to his Oscar nomination, his first, Le Sourd was recently in the running for the American Society of Cinematographers 2014 best feature film award. He has already won kudos for best cinematography on The Grandmaster at Taipei’s Golden Horse Awards. His other credits include Seven Pounds directed by Gabriele Muccino and Ridley Scott’s A Good Year starring Russell Crowe. He is also well-known for his lavish work on commercials for high-end global brands.

Gravity, Emmanuel Lubezki

For Gravity, a lost-in-space sci fi adventure that looks so real you’d think a camera went into outer space to film it, director of photography Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki married elements of traditional cinematography – especially lighting – to the latest in computer-generated visual effects.

The DP worked with director Alfonso Cuarón, with whom he has collaborated since they both were at film school in Mexico City. Gravity was a five-year effort from start to finish. In effect, a virtual camera was created to capture most of the film’s imagery which was then translated by the CGI team at Framestore, a London-based special effects house, into the final result. Real photography, with Lubezki employing an ARRI Alexa digital camera, was also used to film the face of Sandra Bullock, who stars as the astronaut hurled into the void, through the vizor in her spacesuit or within the constructed interiors or parts off several space vehicles. All this had to be seamlessly integrated.

“I had to reinvent myself, learning to use a new set of tools and working with a different kind of crew,” said the DP. “Instead of having a gaffer, I had 12 young artists sitting at computers, and we worked for months lighting the movie and composing the shots.”

As special effects become cheaper, “more directors are going to want to use these tools to tell stories that before were impossible to tell, and to put the camera – the virtual camera – in places they couldn’t before,” Lubezki noted. “I think the language of film is going to change. Gravity could not have been made a few years ago, or even months ago. These changes are coming very fast.”

The DP rejected assertions that what he did on the film, was not cinematography in the conventional sense. “It is cinematography. It’s almost exactly what I’ve done in all my previous movies,” he stated. “Even though I didn’t carry a camera in a spacecraft, we had to create all these environments, we had to light them, to frame and design all of the shots. It’s all the same.”

Lubezki’s Oscar nomination for Gravity is his sixth, so far with no wins. Lubezki received two of his Oscar nominations for films he did with director Cuarón, A Little Princess and Children of Men. His other Academy Award nominations came for Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow and two Terrence Malick films, The New World and The Tree of Life. The DP’s cinematography on Gravity has already garnered him a BAFTA and the feature film award from the American Society of Cinematographers.

Nebraska, Phedon Papamichael

Director of photography Phedon Papamichael’s beautiful black-and white-cinematography for Nebraska adds resonance and meaning to this moody, laconic variation of the classic road-trip movie. The story revolves around the get-rich dreams of a cranky old codger, played by Bruce Dern, who is convinced he has won a magazine sweepstakes worth a million dollars. He sets out on a journey to Omaha to claim it, first on foot and then in a car grudgingly driven by his son, played by Will Forte.

Papapmichael has received his first Oscar-nomination for lensing the film, which is his third collaboration with award-winning director Alexander Payne. It was preceded by Sideways (2004), a serio-comic drinking ramble through California wine country, and The Descendants (2011), a family saga set in Hawaii.

Nebraska had been on Payne’s to-do list since shortly after Sideways, and he had always thought of making it in black and white. That’s the way the film looks when audiences view it in theaters. But due to evolving moviemaking technologies along with demands from Paramount Pictures, the studio behind the film, Papamichael was forced to traverse a logistical road trip of his own to reach that result.

Black and white has not been totally absent from filmmakers’ toolkits over the last decade, encompassing hits including Ed Murrow biopic Good Night, and Good Luck and The Artist, a paean to the silent-movie era. (The last DP to win an Oscar for a B&W film was Janusz Kaminski in 1992 for Schindler’s List directed by Steven Spielberg.) Meanwhile, Paramount was reluctant to go with this choice because of the feeling in some markets that B&W is simply too antiquated. So the studio requested both a B&W and a color version of Nebraska.

That required the DP to shift his strategy. He dropped plans to use Kodak 5222 B&W 35 mm film stock and tested different color stocks and digital cameras to find a combination that could be converted by his colorist into a close approximation of Kodak’s B&W look. He wound up using an ARRI Alexa digital camera, shooting in color and adding grain. The Alexa’s light sensitivity also made it easier to use in low-light situations and in quick on-the-road location set-ups. The Alexa also allowed him to use slower vintage Cooke lenses.

Papapmichael was born in Greece, and grew up in both Germany and the United States. He cut his teeth as a cinematographer working on some of director Roger Corman’s “B” movies, a launching pad for many of today’s best-known DPs. His latest movie is George Clooney’s The Monuments Men, currently in theaters, about the attempt to retrieve art work stolen by the Nazis in World War II. Leading up to the Academy Awards, the DP has been nominated for his work on Nebraska by the Golden Globes, BAFTA and the American Society of Cinematographers.