On Jan. 1, 1863, the new year got off to an auspicious start thanks to President Abraham Lincoln, who declared all slaves free with the Emancipation Proclamation. The impetus for the decree was to allow slaves in the South to join the fight in the Civil War. In Louisiana alone, 350,000 enslaved people were faced with the decision to remain in bondage and wait for Union forces to free them, or take freedom into their own hands. There is a famous photo from that time entitled “Whipped Peter,” taken during a Union Army medical examination, of one such man who chose the latter and suffered dire consequences for his brave attempts to escape.

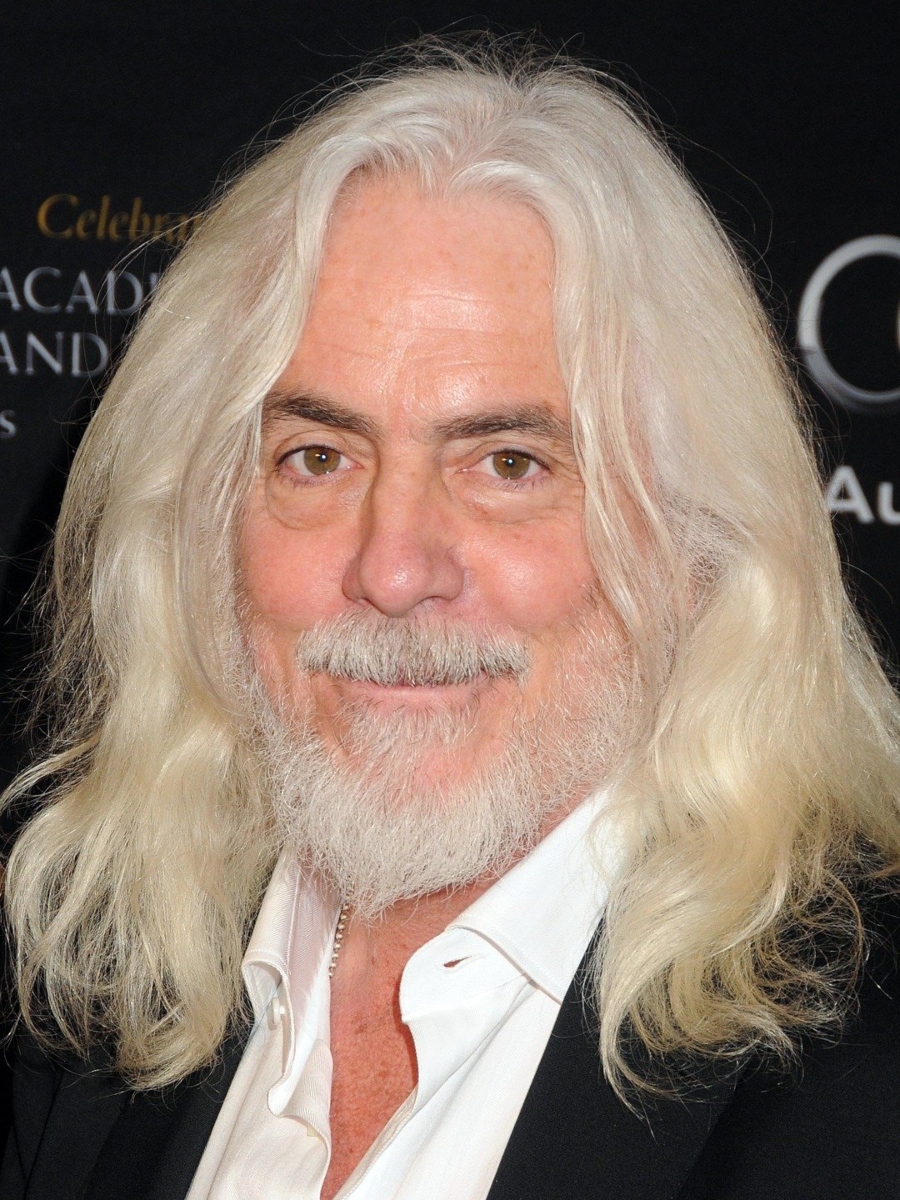

When Emancipation director Antoine Fuqua approached legendary Cinematographer Robert Richardson, ASC to film a historical telling of “Whipped Peter” starring Will Smith as the courageous enslaved man, he initially didn’t want the job. Richardson’s hesitation and reasoning were simple — he was not a man of color and firmly believed that Fuqua should hire a Black cinematographer. That was, until the director convinced him otherwise. Richardson ultimately came onto the project with the understanding that Fuqua’s vision for the story was one of love and not one of color. Throughout their collaboration, the two auteurs formed a deep brotherly bond.

Fuqua is the latest to join the impressive list of directors Richardson has worked with, which also includes Oliver Stone, Martin Scorsese, and Quentin Tarantino. Richardson shot Salvador, Platoon, Wall Street, Born on the Fourth of July, and The Doors for Stone before winning his first Academy Award for JFK. He earned his second and third Oscars for his work on Scorsese’s The Aviator and Hugo, respectively. And his partnership with Tarantino has yielded Kill Bill Vols. 1 and 2, Inglourious Basterds, Django Unchained, The Hateful Eight, and most recently, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

Below the Line recently spoke with Richardson via Zoom from Los Angeles, reeling from the current heavy rains. In fact, our chat had to be rescheduled after a storm took out his internet connection. Richardson shared his own bout with Mother Nature while filming Emancipation in Louisiana, where Hurricane Ida wreaked utter havoc on locations. The heat and humidity, as well as the potentially lethal environments of the Louisiana Bayou, were also difficult for the seasoned cinematographer, who is not a fan of slithering wildlife. Richardson also shed light on his discussions with director Antoine Fuqua about the film’s look and tone, as well as how he achieved those sweeping widescreen cinematic moments on horseback or on the battlefields, where he was able to hone in on the intimate realism for which he has become known.

Below the Line: How are you faring with the weather in Los Angeles?

Bob Richardson: It’s raining heavily. It’s rained for pretty much the whole week. Well, L.A. needs it, but it also needs a better water system. They don’t know how to capture it. They just let it flow right through. I mean, for a town that has known drought, why is this not being done, like, a generation ago? Somebody’s making money off of this, I would gather.

BTL: Well, that’s another story entirely! But speaking of water, can you talk about the scene where Will Smith and others have to cross the bayou and how that was shot?

Richardson: The alligator sequence. Originally, it starts with a shot, which is established, then riding along the edge and dropping down to Will. Will takes the bandage off his leg, puts it in the tree stump, swings across, and falls into the swamp, and it crosses over to the place where he hides when all the men ride up. It was done with a crane. And then once the alligator sequence begins, it’s a combination of many, many different factors. Rob Legato is a VFX supervisor who also served as a second unit DP and shot other scenes. We shot with his VFX elements, which are all separate. He built a large aquarium in front of a large monitor that was in color, and Will was able to go into that clean water space and act with puppets. So I had elements — a tail element — and then part of it was shot on location with the stunt double with just the tail or the head. It was made up of many different parts.

BTL: I want to talk to you about the color palette or lack thereof. Tell me how that came about in your discussions with Antoine Fuqua.

Richardson: It came about based primarily upon the photograph, Peter’s photograph. We saw so much power in that image that we decided that it would be best for the film to slide into that particular palette, to use it as the center of the film [with] respect to how to develop the look, which is why it led us towards a black-and-white palette.

BTL: There were scenes where you could see the look of the fire, which had almost an orange glow to it. Was that intentional?

Richardson: Yes. Yes. The orange was dominant, and sometimes we allowed some green thrown in. We allowed red in, and it was defined in the same way that a musical score would be. So, once the cut was completed, Antoine and I would discuss whether it would be better to have a little bit more or a little less, and use it as a tool for enhancing an audience’s experience, shifting their minds, and allowing them to either refresh or engage, you know? That was the basic concept behind the allowance of color within [the] black-and-white.

BTL: Bob, if you could take me back to that initial conversation you had with Antoine, what was the vision that you shared?

Richardson: Initially it was, I didn’t want to be involved with the movie. I’m white and I felt that it might be better to have a cinematographer that was of color. I love the subject matter, but I felt maybe someone of color would be better. And Antoine defined for me that this is not a story of color. This is a story of love, and it’s a story we need to tell so that future generations won’t make the same mistake again. It doesn’t matter whether it’s this mistake or whether it’s the same error that was made, you know, [with] respect to the Holocaust or the genocide that’s happening around the world in various places like Ukraine. There are so many issues that we’re fundamentally going through in the headlines of our news today. He sees this as an example of, not simply slavery in the United States, but of all issues that surround us, George Floyd on, all the way to the border crossing and the whipping that took place [in the film].

BTL: Can you give an example of current issues that might have coincided with shooting this film?

Richardson: That whipping scene on the horse took place on a border that is very similar in [its] timeframe, meaning we shot it as it was actually happening. The whipping of Peter occurred literally a day after a border whipping in which a border patrolman on horseback came down on people attempting to cross over, and whipped them. And that took place within a day or two of the actual event that we had already planned. So it was clear to us that so much of what was taking place in the present was in the past, and it would be wonderful if we could, in some ways, instill generations to not make the same errors we’re making now.

BTL: That is so interesting. What do you remember most about the first day of shooting?

Richardson: I remember so many issues about that first time. Understand that we’re shooting in Louisiana, where temperatures regularly reached 100 degrees. Every day, the humidity was at the same level, nearly 100 percent. We were intensely involved with Covid happening. So in one particular sequence, there are over 300 people or more that had to go through a Covid test in a parking lot, [and] wait until the results came back. You could not exit until it was a negative Covid test. And that took 45 minutes to an hour for every one of us, by the time we actually began shooting.

BTL: What about the challenges of dealing with the elements in the bayou?

Richardson: It was a nightmare dealing with [the] physical world. I’m deeply frightened of snakes. It’s instinctual. You could show me a pistol and I don’t care. You show me a snake and I leave off the ground. And joking aside, there is something primal about that fear. Alligators don’t do the same thing, but I know that they kill ’em. So I was afraid of those elements. The mosquitoes [and] the bees, I was able to deal with, but as to everything else… I hated, hated [the] snakes!

BTL: From the swamps to the battlefield scenes. Describe the scope of shooting that.

Richardson: All of them were huge. We didn’t have a lot of days. I think we shot it in six, or seven, or eight [days], but it was massive. We originally thought we would go about shooting that in one shot, and I’d imagined it as one long drone shot that ended on Will, but the capability of a drone to complete that kind of task for a VFX person meant that you couldn’t add or subtract because of the irregularity. And so we did it with a cable camera in four different positions, and that allowed some repetition, at least to the level at which Rob Legato could get at it. It was complicated, to say the least. Fortunately, because the concept did not work, the battle sequence is much better than if we had planned it in one shot.

BTL: What other happy accidents have you had in your career?

Richardson: I’ve had a few of those in my life, haven’t you? I wouldn’t call this one happy, but we did get the Hurricane [Ida], and it caused a five-week delay in the film. Louisiana was deeply hurt by the hurricane in so many ways, but the time allowed us as a film unit to find, I think, greater strength and unity, because not only did we try to work with the state and the issues they had as much as we could, but we also as a unit became unified like a family. It’s complex to actually define that accurately for you, but we joined in on what Louisiana was going through. The film became less important for all of us. The important element was what Louisiana was going through and those who lived there.

The positive, if you can call it a positive, was that some of the swamps were badly damaged and many of the locations were badly damaged from the very high winds because those winds went right through most of our locations, the heaviest part of the hurricane, and the result was that it didn’t have the same lushness, but what it did have was a sense of being severely damaged and more brutal. We found a way to utilize that as an element in the film, so the landscapes lost some of their cover and the lushness became more broken, much as he [Peter] was broken. And I believe it aided us in this regard. Beauty is one thing, and Antoine had always spoken about trying to make this film brutal and beautiful, and now the landscape, which was absolutely beautiful, looked brutal — more brutal than we would have been able to shoot if this hadn’t happened.

BTL: Talk about shooting horseback riding scenes. How was Ben Foster’s seat on the horse? He looked really good.

Richardson: When Ben first started, he didn’t look so good. But Ben took the role seriously and trained intensely, and he became a vastly superior rider. That man is not only a brilliant actor, but he is also a very serious actor. I mean, he looks like a master, and he did sit very well. There was no glue involved. [Just kidding], that’s not a thing. He just kept himself in that mode. He’s a remarkable man. Most of those scenes were shot via what we call “the edge,” but it’s a camera car.

Generally, it’s a Porsche or Mercedes with a crane on top of the car, and you operate from inside because it’s the only thing that can keep up with the speed of a horse other than just panning or doing something similar to that from the ground. But to actually track alongside or do moves that are very complex, we utilize the edge with a very stabilized head. I’ve used it all the way back to the time when we were shooting The Horse Whisperer.

BTL: Very cool. Since you’ve been around and doing this for some time, what looks or camera techniques have you invented or perfected over the years?

Richardson: I don’t think I’ve invented anything. I use headsets a lot, and that was not the norm when I started shooting. It allows me to communicate with the heads of departments and ADs. I make it a one-way system, so I don’t allow feedback or talkback. It’s just me talking. On Casino, some of the camera moves were so complex that I didn’t know how to make them. [Director] Marty [Scorsese] was just demanding certain moves that I couldn’t step over. Because I operate every film, I couldn’t step over the dolly arm. So I asked the key grip at that time if he could utilize what’s on a crane, which is that you can swivel on a crane. And so he built something we call “The Bob Seat” that allows you to ride on the arm so you can move 360 degrees on the arm with very little effort, and that allows for so many moves that are extraordinarily difficult and cumbersome for an operator.

BTL: There’s a scene I wanted to discuss with you where Will is chained up and a fiercely barking dog is being held back on a leash by Ben Foster’s character. What’s it like to wrangle those dogs? They really looked like they were going to eat him.

Richardson: That dog was literally that close. As you can see, the dogs are well-trained. They’re not meant to bite, but you saw it get, like, right near his throat. It’s like, you have to hold that dog because that dog is aiming for a target that they place at the neck. It’s a piece of food, and you can’t see it; it’s out of sight, but that dog went for it, and Will did not move. You don’t move. You have to stay there and hold your firm stance because if you actually move towards it, the dog will take your throat, in this particular case.

BTL: Would you say that Will was fearless in the role?

Richardson: Will was an astounding human [with] respect to his lack of fear of the elements. They say they have all the snakes out when you see him in the swamps. They say they have all the alligators outside. I can assure you that is not the truth. He and all the actors that moved through those spaces were very clearly aware. However, the majority of those animals do not want you. They prefer you not to be there, and if you’re a threat, yes, but they don’t want to bite or attack. They would rather be away. We were fortunate that nothing happened, but for all of us, it was a constant noise in our heads that we had to be very, very aware that we were dealing with an environment that was deadly.

BTL: Yes, very much so. Coming full circle, were your concerns about taking the job put to rest?

Richardson: I think that he was absolutely correct in his assessment that this is not a story that you have to be of color to shoot. You don’t have to be white to shoot it. It would’ve been nice if a person of color had shot this because they have less opportunity to be at the helm of films, but that didn’t happen. I would still try to sway the vision toward someone of color if I were asked again to do this movie. And if they didn’t, if they chose me, then I would step into that. You know, it’s like if Kathryn Bigelow calls up and says she wants to make a film, I’m with her. I don’t have to be a woman. I think that it’s possible to work with many different directors of different races and genders, despite being a white male.

BTL: Describe how your relationship with Antoine developed throughout this process.

Richardson: Antoine, I would describe as my brother, We joke about this and we say we’re brothers from another mother, but we think very much alike. We can literally start and finish a sentence together, and that happened almost instantly upon working together, for a very unknown reason. I just finished the third Equalizer with him and am looking forward to a third film with him directly after a short break here. I adore the man, and we were always two of a kind. We’re like twins. It was beautiful, and it [has] developed from that point into a deep friendship as well.

Emancipation is now streaming on Apple TV+.