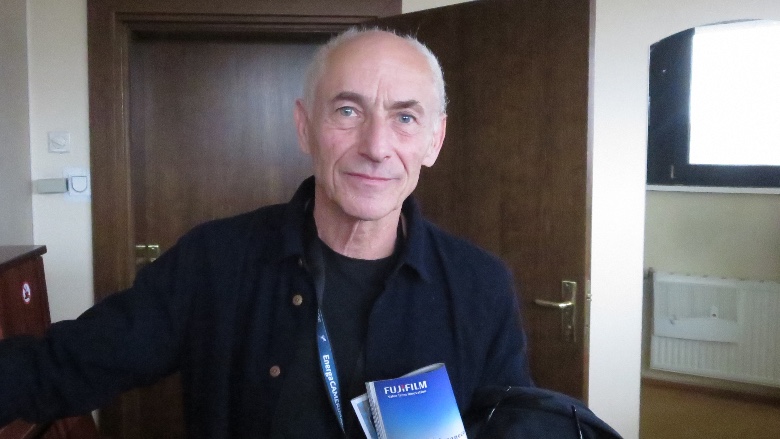

This year, the EnergaCamerimage International Film Festival presented its Lifetime Achievement Award to Philippe Rousselot, ASC, AFC. In a career stretching back fifty years, Rousselot has worked with a wide range of directors, including John Boorman, Neil Jordan, Tim Burton, Stephen Frears, David Yates, and Miloš Forman. He received an Oscar for his cinematography work on Robert Redford‘s A River Runs Through It.

Rousselot broke into the industry as a clapper loader on Eric Rohmer‘s My Night at Maud’s and shot his first feature, Earth Light, the following year. Since then, he worked in a variety of genres and styles, from biopics, such as The People vs. Larry Flynt and Denzel Washington‘s Antwone Fisher, to special effects blockbusters like the Fantastic Beasts franchise. His latest film, Without Remorse, is a Tom Clancy adaptation, directed by Stefano Sollima (Sicario: Day of the Soldado), which will be released by Amazon Studios in 2021.

“I always wanted to make good films, but I never had a career planned,” Rousselot told Below the Line via a Zoom call. “I never even imagined I would work anywhere but France. I was just anxious to get a job.”

By his own account, Rousselot was not a household name when John Boorman chose him for The Emerald Forest.

“We had dinner in Paris, and he ordered oysters, so I ordered the same thing. It was August. John told me later on, ‘This French guy eats oysters in August, he’s probably not that smart.’ Actually, I think he had a hard time convincing British DPs to spend six months in the jungle. He wanted someone to go along with the adventure.”

Few films have captured the splendor and danger of the jungle as The Emerald Forest. The two also collaborated on Hope and Glory, an imaginative, heartfelt story about children growing up in post-WWII London. It was filled with visual set pieces like a complicated sequence in a railway station.

According to Rousselot, Boorman was so knowledgeable, so precise about film that he worked out his shots down to camera height, lenses, and the number of extras, months before production. He even complained when a designer built a set three feet higher than necessary.

“I would say Tim Burton is closest to Boorman stylistically,” Rousselot said. “The films they make are very different, yes, but Tim is also thorough in his preparation. He only shoots what he needs, he doesn’t overshoot with the hope of creating the film later in the editing room.”

Rousselot spoke frankly about projects that did not live up to his initial expectations, pointing out that one thriller he shot was “motivated by political ideology, political concerns with which I totally agreed. It’s difficult to make a film that doesn’t start with characters, but with an agenda.”

Director Stefano Sollima approached the politics in Without Remorse in a different manner.

“If you’ve seen his film All Cops Are Bastards, he deals with political issues, but he does it with extremely detailed observations of people,” Rousselot explained. “Yes, the film has politics, but it starts with people. In the same way, the Navy SEALS in Without Remorse are manipulated by politics, but they are people like you and me. Except their body build is different.”

Like most Tom Clancy adaptations, Without Remorse has its share of action scenes. “We kill a lot of people,” Rousselot joked. “There’s a lot of blood.”

The cinematographer employed three cameras for the big action sequences, in part to save time re-dressing sets after squibs, explosions, and stunts — but also to preserve the dynamics of the action and to help the editor match shots. His team devoted several meetings and tests to figure out how to depict a plane crash, “measuring things so that the camera wouldn’t be crushed. Every problem is a gift, because that’s how your neurons are restored.”

Cinematographers Raoul Coutard and Néstor Almendros were strong influences on Rousselot, Almendros “in a way for how he would light his scenes, but more his way of thinking. Never start with what you know, for example, but work with what you discover. I had this saying from a while back, ‘Experience is great in a time of crisis, otherwise it’s a weight you have to drag with you.'”

According to Rousselot, Almendros was originally an advocate of the Cuban Revolution, but left the country and his parents when he became disillusioned with Castro’s regime.

“Fleeing Cuba was not looked upon well by the leftists in Paris,” Rousselot pointed out. “It was very traumatic for Néstor, he had to reinvent himself.”

Almendros also helped reinvent how cinematographers approached lighting.

“He came from documentaries,” Rousselot explained, “so he had an instinct of how light worked in the real world. He would look at a set and say, ‘There’s a window, okay, how do I reproduce the light that would come through it?’ When at the time the solution for most DPs was, ‘I have to use a 10K here, that’s my key light, and then I’m going to put a fill and a backlight because that’s what people do.'”

When Almendros shot Days of Heaven entirely during “magic hour,” Rousselot said “the grips hated him, because they wanted to use arcs and things like that. They told the producer that Néstor didn’t know his work. He had to fight some battles.”

Rousselot’s first entirely digital film was Shane Black‘s The Nice Guys in 2016. While he admitted that he is still nostalgic about film, “on the other hand now I can sleep without fear. Well, that’s not really true. By a certain point in my career I knew exactly what was on the negative when it went to dailies. There were no major surprises unless it was scratched or harmed in some way.”

“I don’t want to make ideological points about technique,” he continued. “Equipment is subservient, it’s a tool. No one has proven to me that films are bad because they were shot on digital.”

Along with digital cameras, one other major technical advancement has changed the way Rousselot shoots: LED lights.

“Now you don’t have sweaty actors,” he laughed. “You don’t have to switch the lights off immediately after ‘Cut’ because it’s so hot everything’s melting. They are so practical, so easy to use, so immediate.

“They don’t change whether films are good or bad, however. Unfortunately, they didn’t improve the quality of scripts. But I didn’t expect them to.”