When Oscar-nominated production designer Barbara Ling first read Quentin Tarantino’s screenplay for Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, she had the reaction one might glean from reading a novel. “When you finish it, you are gob-smacked,” Ling said of Tarantino’s script, laced with both fictitious and real characters. “He has all of these asides about who these people are—the enormous scope of this world, which is a way to tell the story.”

Sitting with her director after absorbing the script, the two artists devised an approach to determining the film’s design concepts from scene-to-scene and section-to-section. “The biggest thing we did is immediately get into a car and start driving around L.A.,” Ling revealed of her first ever experience with Tarantino. “It’s a visual approach because you are doing so many areas – a big spread-out town.”

Given the 1969 setting of the film, Ling and Tarantino selected choice locations for exterior photography in and around the city of Los Angeles. “We knew that it would be a difficult permit process,” she said. “We started [to] see what was even possible for us to achieve. The city was magnificent about giving us permits. You [were] trying to bring the flavor of that time. We’ve never been a city of preservation— L.A. takes down [structures] faster than anything.”

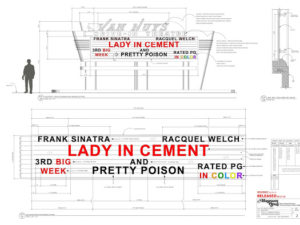

One location Ling and Tarantino deemed essential was in the San Fernando Valley. “The Valley became a very important element for him,” Ling conveyed. “We rebuilt the Van Nuys Drive-In [and] one of the great drive-in marquees, working within Panorama City. I could build signage in the sky.”

For Tarantino, 1969 was the year he turned six-years-old and first noticed prominent movie theater marquees on Hollywood Boulevard and in Westwood Village. “There were areas that were key for Quentin,” Ling noted. “Westwood was an iconic place in the 1960s. Can you imagine a six-year-old laying in back of his mom’s car, looking out the window? That was the point-of-view that we used.”

In formulating her modifications to practical locations across Los Angeles, Ling needed to work closely with existing infrastructure. “You can’t stop a city,” she said. “You have to work with them, bring cranes in at night. We had months [to prepare]. We needed that in the process of getting a permit, when we would have to close streets, and we had to back that up to six weeks, eight weeks, to be able to change over the storefront to the look—an enormous amount of jockeying between the city and the vendor that owned the building.”

Most of the edifice owners that Ling approached were excited to recreate 1969 Los Angeles. In Westwood, Stan’s Donuts had been an institution since 1962, while the working movie theaters The Bruin and The Fox were amenable to installing facsimiles of their original marquees. “Long overnights to get that,” Ling revealed. “The wonderful thing is that people loved seeing neons and original things go back up.”

Recreating Hollywood Boulevard of 50 years prior was much more intensive than doing so in Westwood. “Tourism never stops on that street,” Ling stated. “The tourists got to see this happening. In shooting, Quentin was extremely generous—he controlled the crowd: ‘Pedestrians can stay on one side of the street. When I say rolling, you have to all be quiet.’ With the magic of Twitter and Instagram, that crowd of 200 turned into 8000 the second night of shooting. We were very lucky that all of this worked so beautifully.”

Additionally, Los Angeles’ iconic freeways presented a formidable challenge. “We only had one hour to bring the period cars on,” Ling explained. “You had to stop the traffic. They let us change the signs, put in our own billboards on original buildings. It’s who we were—we’ve become the research for the next movie.”

To replicate a Western movie set of the time, Ling had a construction crew on the Universal Pictures backlot to rebuild the original Western towns which once stood at the studio. Other sets were located at Spahn Ranch in the Santa Susana Pass and on stage in Santa Clarita.

Lastly, Ling reflected upon the art directed results in her first Tarantino film. “Quentin, being his ninth film, he’s got quite a repertoire of fans and an incredible base of people who love his films,” she related. “He’s an amazing, genius director that you get to be attached to for a brief moment in your life. I was swept away—an amazing experience.”

For Oscar-nominated costume designer Arianne Phillips, not having worked on a Tarantino movie previously, the screenplay to Once Upon a Time in Hollywood fully mesmerized her, much as it did Ling upon first read. “Once I read the script, there was no question that I had to do this film,” Phillips remembered. “I cleared my schedule and did 80 hours of research to put an extensive presentation together for Quentin. At the first meeting, I got the job. Just getting the job was akin to getting the nomination—I didn’t really know if working with him could happen. He has a loyalty to his crew and has worked with an incredible array of costume designers who I respect and admire.”

One certain aspect of the film’s director-designer relationship included possessing similar points of reference. “There is synergy that Quentin and I have,” Phillips unveiled. “We’re the same age and had a similar relationship to Los Angeles as kids. He grew up around L.A., and my grandparents on both sides lived here. Quentin referred a lot to the memories he had going to Hollywood Boulevard and the Cinerama Dome with his mom and dad. Going to Grauman’s [Chinese Theater] and Hollywood were vivid memories for me. I related and understood these lovely memories that Quentin has.”

In conceiving of the principal actors’ costumes, Phillips detailed that she was moved by the story’s fictional narrative surrounded by real events, people, and places. “There’s so many opportunities to tell this story,” she said of her costume department, noting, first, all of the television shows and films in which fictional Rick Dalton appears. “And who Rick [played by Leonardo DiCaprio] and Cliff [played by Brad Pitt] are when they are not in front of the camera. Telling a story about Hollywood was a treasure trove to move the story forward.”

Pointing to the cultural upheaval in 1969 Los Angeles, Phillips revealed how those changes in American society, specifically in California, would be reflected in her costumes. “It was changing through what people wore,” she said of the infusion of youth culture into mainstream life. “That’s really at the heart of what the story is about: an actor that finds himself in 1969 who is in that early-1960s/late-1950s world that the character used to be. A hippie kid, a student, an older lady, a working man—the way people dressed reflected what was relevant for them at that time. A real cross-section—the responsibility was being able to show that. It wasn’t a story set in a small window of what people wore.”

Working with a big team, including a costume supervisor, set costumers, and dressers, Phillips ensured that every character, even those with smaller roles, had his or her own backstory. “When you look at the background actor, we look at their face and find out who their character is,” she remarked. “You feel that you have every kind of faction of people living in Hollywood. Rick Dalton is moving through a changing Hollywood.”

Even though Phillips received a wide selection of scripts after wrapping Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, she took a break from filmmaking through most of 2019 to focus on theater and fashion work. “I did that purposely because I really knew that whatever was going to follow up Once Upon a Time had to be worthy,” she confessed. “I grew some extra muscles as a costume designer, being able to think about how the costumes moved the story. It was an incredibly multi-layered opportunity and had me completely engaged every single day on the set.”