Last year’s Candyman sequel, which hailed from director Nia DaCosta and her co-writer Jordan Peele, was one of the quiet hits of last fall, hooking nearly $80 million worldwide in the middle of the pandemic.

The horror film was a direct follow-up to Bernard Rose‘s now-classic 1992 slasher movie, which told the urban legend of Daniel Robitaille (Tony Todd), aka “Candyman,” the ghost of an artist and the son of a slave who was murdered in the late 19th century for his relationship with the daughter of a wealthy white man.

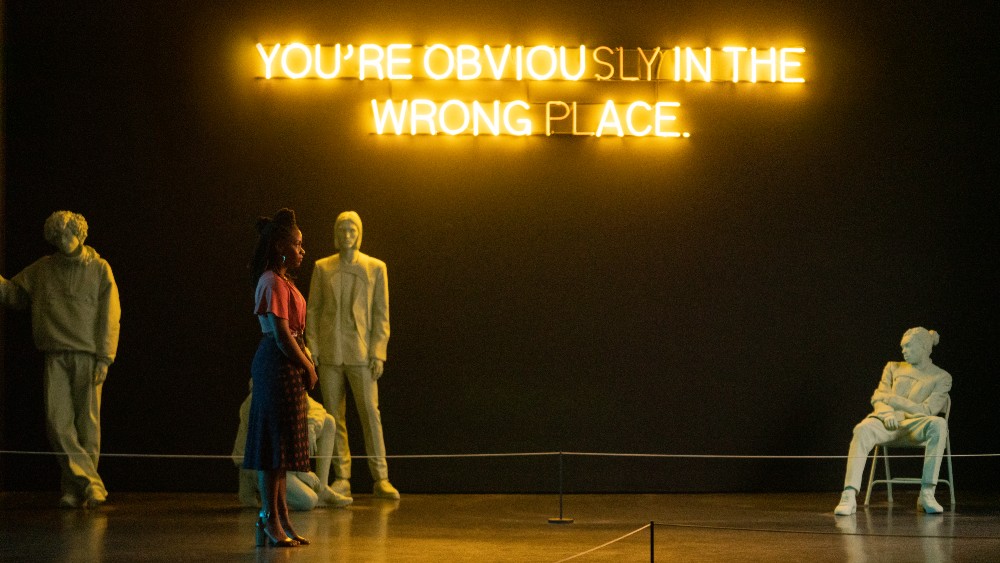

In this new film, residents of the Cabrini-Green housing project are haunted by the memory of Sherman Fields (Michael Hargrove), a man with a hook for a hand who tempted children with razor-spiked candy. Decades later, when visual artist Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) starts to obsess over the urban legend and have strange visions, we’re left to wonder whether he’s slowly becoming the latest to assume the macabre mantle of Candyman.

One of the highlights of the original Candyman was the gorgeous score from Philip Glass, so composer Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe had some big shoes to fill, though he was more than up to the challenge. Not only was Candyman largely a hit with critics and audiences, but it has found itself in rare company for a horror film — on the Oscar shortlist for Best Original Score.

Lowe’s score is full of the synthetic, electric sounds and arrangements that have come to define the rising composer. Lowe recently spoke to Below the Line about his involvement with Candyman, which is his most high-profile film score to date, and about the creation of the creepy, metallic noises that provide the perfect chilling soundscape for the unsettling film.

Below the Line: Rob, let’s start with how you came to this project, considering film is not the focus of your career. Why did you say ‘yes’?

Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe: I was approached in February 2019. I received an email from the production company asking if I was available to score a horror film for them. The company was Monkeypaw, and I’m a big fan. I knew they had optioned the Candyman story from MGM, so I assumed that’s what it was.

They have done really thoughtful things, some really creative work, so it was something I wanted to be involved in. Eventually, we had a meeting and talked about the project. Ian Cooper, the producer, first initiated this contact. They said they had wanted to collaborate with me artistically for some years.

BTL: How much did you listen to the original Phillip Glass score when you were working on your own version, and at what part of the filmmaking process did you actually begin composing the score?

Lowe: Very early. They sent me the script and I read it, and then I went to them with very clear intentions of what I wanted to do, with a very specific, multi-faceted proposal. First, I was thinking, as you say, about the Philip Glass score and also [original story writer’s] Clive Barker’s larger storytelling universe.

Second, I wanted to be as involved in the production as possible. I felt that the earlier I came in, and the more time I had to work on the idea, the more complex and more fine-tuned I can get things. This is true for every film project.

Third, I wanted to be on set while they were shooting and also do some on-location sound recordings to transport the energy of the actual spaces into the film itself, sonically. I wanted to be able to see Nia work in real-time. I think it was beneficial to our collaboration throughout that I was able to do that.

BTL: What were some of the themes that you discussed with her and that you ultimately incorporated?

Lowe: Nia and I actually worked very closely throughout the film. We had a very open dialogue about what the project was and what ideas we each had for it. For my part, I had a lot of ideas about ghosts and apparitions. I also wanted to think about the characters in the film and the complexity of their histories. Particularly the victims throughout the history of the folklore, what those spirits brought to the story, and where they existed in the landscape of the film.

I was very focused on the original Candyman in the first film — his story, and not only his story, but his lineage going back all the way to slave trade lines. I was thinking about the way mythologies were handed down orally. I was thinking about Western Africa and the sonic elements of traditional music there. I tried to weave everything I just mentioned into the score itself, and I tried to present a score that had dread, but I also wanted it to be nuanced and have dynamism. I wanted some whimsical elements too, so not just heavy dread.

BTL: In terms of the acoustic elements, can you give us some examples? I know you used the cello and a lot of electronic elements.

Lowe: Definitely those two. There was contrabass played by Matthew Morandi. There were certain acoustic elements that were made by metal objects and percussive elements that came through with woodblocks equipped with contact mics. I did not use an acoustic piano, but I did use an electric one.

On some of the compositions there was a lot of voice, distorted, electrified. So there were not a lot of acoustic instruments, but there was a lot [of] blending all of these elements to create a world in which I could play with this concept of illusion, and present a sound that was made acoustically and recorded with a microphone but then processed in a way that made it sound surreal. The sounds were flipping over on each other.

In general, that is how I work anyway. It’s a part of my practice and I like to do it. I would prefer to have a sound that you weren’t quite sure what it was and maybe makes you lean in a little bit more because of the curiosity as to what that may be. You also have to make sure the sound is a character within the film that carries its own narrative but does not go so far as to get into the way of the film. It cannot be overwrought and [it] has to live, well, organically and naturally in the space.

BTL: On the voice element — why use that? I heard illusion, making you lean in. Is there anything else? Do you find it scary?

Lowe: The voice is my main instrument. A lot of the compositional work that I do, performative work that I do, involves my voice. Processed and unprocessed. I play with the range of my voice, with how the sound is created inside of the body, how you position the body. Where you sing from in the body creates different results. The voice is such a dynamic instrument, it can go so many places and have so many sounds, that I just find it very interesting. It’s nice because everyone’s voice is individually theirs. The sort of things I do with my voice have a uniqueness to them.

All of this also plays into the concept of the multiplicity of voices within the story itself. What I was saying before — you can get both elements of the individual complexities of the characters and victims. You have a whole world of characters that are interwoven and moving around. I wanted to be able to use the voice in a way in which it carried each of those histories forward, sort of like the sum of all of its various parts.

BTL: So it sounds like you were composing even before shooting began?

Lowe: Yes. At least in writing.

BTL: Tell me a little more about the collaborative process you shared with Nia DaCosta.

Lowe: It was constant communication. Film is such a communal and collaborative art form that you really do need that. You need to be able to know where everyone is at any given point in time so that the thing flows naturally. At the end of the day, we are all striving to get to the finish line with a film that lives in the world in the way that it is supposed to. Our collaboration was a very steady and productive one. There were a lot of similarities in ideas.

As I mentioned, for me being able to come in early and to work as in-depth as I like to work in film is important because of the critical relationship between the visual and the aural. To come in after the film has been shot and cut, probably does not work. Maybe you can have an integration, but it’s much harder to achieve. So being able to give Nia sound that she can live with and think about as she is making the film, the sound is then having a conversation with the picture. The collaboration is working in both ways. I’m being influenced by the shots, and the sound is influencing what she is shooting. It becomes a symbiotic relationship, which is important to me.

BTL: It sounds like you enjoyed it!

Lowe: I had a great time. I was able to come up with an idea and clearly state why I was doing it, in a way, and why it sounded the way it did, and she could tell me what she thought or ideas she had not shared previously.

BTL: How does it feel to be included on the Oscar shortlist for Best Original Score?

Lowe: Strange. Certainly not expected, but it’s quite bizarre. Obviously, you do the work for the pleasure of it, you do it because you love the craft, but it’s cool in some ways to be in the conversation. It is totally new to me. I have said [it] before and I will say it all day long — I enjoy the work so much. I show up and do the work because it’s a part of me. It’s not a job for me. I have a vested, personal compulsion to do this type of work. I love creating, [and] making something communally and collaboratively with someone. We’ll see what happens with the Oscars.

Candyman is on the AMPAS shortlist for Best Original Score and is currently available for rent/purchase on VOD/digital platforms.