Patrick O’Keefe and Dean Gordon both worked as art directors on the first Spider-Verse movie, with O’Keefe handling production designer duties on Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is the sequel to the 2018 Oscar-winning film. The film sees Miles Morales and Gwen Stacy venture across the Multivese and meet other Spider-People protecting its existence. In battling Spot and his dangerous scheme, it puts Miles at odds against other Spider-People.

Both artists tell Below the Line about the challenges that went into designing the sequel, especially with all the new worlds that the film is visiting. In addition, they also discuss how the film is a representation of the world we live in. For example, placing a Protect Trans Kids sign in Gwen’s room is not a big deal. The sign did not go unnoticed when the first trailer was released in 2023.

Recently, O’Keefe and Gordon spoke with Below the Line about building Across the Spider-Verse‘s otherworldly yet familiar worlds.

Below the Line: Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is one of the best films of the year. Did you feel any pressure in improving upon its predecessor while working on the sequel?

Patrick O’Keefe: I think one thing I’ve noticed—Dean and I were actually both art directors on the first film and so a big feeling, at least within the art department, since it was sort of us carrying the torch again, was less so like, Oh, my God, how do we improve, more so like, Oh, my God, there’s so many things we wish we had got to try out. There’s so many ideas that we wish we got to do. There’s so many bits of technology on the first film, and even on the second film, now that we’ve done it and it’s up on screen, that we were pushing on and pushing on and pushing on, but never got quite as perfect or as far as we wanted.

I didn’t really feel a lot of pressure in terms of how do we make it better. It was more like, we want to make it better, we’re excited to have the opportunity to make it better, and so let’s go. I’ve got to give it up to Sony from an executive point of view that they were very much like, “You guys killed it. Let’s go. Keep going, keep going. Push it further, push it further.”

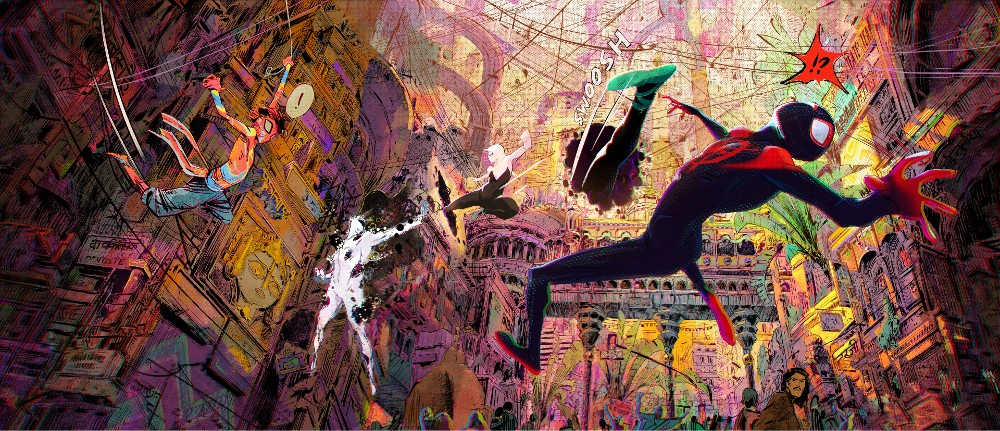

Dean Gordon: It was more to go to new places and to try new things. We’re going to all these new worlds and so we didn’t want to repeat ourselves. Every world had to have its own look and so the pressure was more to develop those looks and just to go farther than we had gone on the previous one. The push is always more further. How much how much farther can you go with this? Give us the extreme version of this. That’s kind of the creative pressure, just to see how far you can go.

BTL: As far as design went, what were some of the biggest challenges?

O’Keefe: Oh, boy. Knowing that on the first one, we touched on Gwen’s world for a teensy tiny bit and then knowing going into the second film, how much more heavy lifting storytelling, one thing Dean and I sort of assessed at the start of the projects is okay, stylistically, what’s happening in this portion of the film? Is it just gonna be like, we’re in and out and it’s a gag? Or is it, we’re going to need to have an emotional connection to the characters? We want people to laugh, cry, people are going to be talking.

Knowing how big a part of the story Gwen was going to be, that was probably one of the biggest challenges is how do we take that style of her comic books and give it the emotional range that her character deserves. Gwen is a highly fluid character, emotionally fluid character, and we wanted that emotionality to end up on screen visually. We needed to pull out every trick in the book to have the flexibility and give the directors the flexibility to manipulate the environments and the render style as much as we could. I think of all of them, Gwen took the most amount of work because of just the complexities of her character.

Gordon: Yeah, I would agree. One of the things with her world is that she was always described by the directors as a mood ring. What she was feeling is what you should be seeing expressed within the frame. It didn’t have to be logical. It didn’t have to be consistent from shot to shot. It needed to be expressive of her feelings. Part of that was to make sure that from shot to shot, for example, in the Guggenheim, we tried to vary the look, even techniques, from shot to shot. That was one of the challenges was actually avoiding consistency, which is what you normally would strive for.

O’Keefe: Yet amounts to a lot of work because instead of like Dean says, you have like a master shot and another shot and great, now we’ve done the color keys and that’ll serve for 30 or 40 shots. Here, the emotion of the film is changing with every line and so the look of the film needed to change as every line was delivered. There’s brand new technology in there. The ability to have 3D geometry that is represented in paint strokes, which will then bleed wet and a wet, because the emotions are changing within the scene. That’s a difficult concept to wrap your head around and to realize that’s what’s needed for the film and then a whole other level of difficulty to actually work with and make the technology work to do the storytelling that we need.

BTL: I’m glad you brought up Gwen. One of the things that I noticed early on when the first trailer came out was the blink-and-miss-it Protect Trans Kids sign at Gwen’s home. At what point in the process did this get included in her home?

O’Keefe: That wasn’t a huge decision that got made. It wasn’t like there was a meeting about it or anything like that. The film is representational of the world we live in and that is an aspect of the world that we live in and an aspect of the filmmakers making the film as well. It wasn’t a big decision. It wasn’t a huge to-do.

Same with Miles and the Black Lives Matter pins on him or any other representation that goes in the film. It’s not like we have a checklist of to-do’s or a big discussion about it. It’s really just like, let’s turn a lens on the world that we are trying to represent and make sure that we are inclusive of it. That’s really how it came about.

Gordon: I think it was just during set development, going through what represents this character. You have toys from her childhood as well as her current interests, both music and sociological. What is she responding to in her world today?

BTL: Well, being a transgender American myself, it did not go unnoticed.

Gordon: That’s good.

O’Keefe: I think the thing about inclusivity of all kinds is that in our attitude towards it is these are not things we need to make a meal out of. These are true things about the world. And for some people, that hits a chord, and that’s great. Not to liken being trans to motorcycles, for example, but I know nothing about motorcycles so we got somebody who knows a lot about motorcycles to design the motorcycle so the motorcycle people in the audience are like, oh, yeah, that’s a Fender Chopper Heimer thing—like I said, I don’t know—and they feel like their thing is also being represented.

It can be anything from a lifestyle to to your favorite comic book to Jamaican beef patty. I think just being authentic to who our characters are in the story we’re trying to tell is the intention and then it can resonate with some people and if it’s not for you, then you don’t really notice that much and that’s fine, too.

BTL: There have been a lot of advances in animation technology through the years. In what ways have those advances benefited the film the most?

Gordon: I’ll give you a clear example. Somebody said to me that, after seeing the movie, that what we did in Gwen’s world, was what we were trying to do—I was at Disney at this time, when the Tarzan movie was being made—with Deep Canvas trying to represent brushstrokes and space describing an object three-dimensionally. Here it is, 20 years later and we’re representing brushstrokes in space, literally anywhere in space, and kind of achieving that effect that the people were after 20-25 years ago.

Having Imageworks develop their line tool so it could describe objects with different weights of line, different scratchiness of line, different splatter line, baldness, actually have a change in space as it goes like a car from foreground to background. The amount of linework drops off as it moves back in space. Just having those tools is kind of what allowed us to get away from old school CG movies, which were very representational, very live-action looking, and actually striving to get more and more live-action. The new tools allow us just to be more expressive so the look of the film is literally driven by artwork. When we do our artwork, we are not thinking about is Imageworks going to be able to make this. We present a target and to their great credit, whatever we present, they can make now, and it allows for such a greater range of expressiveness.

O’Keefe: Yeah. I think Dean touched on something very important that we’re very fortunate to be existing in a time of—it’s like back when the camera was invented, all of a sudden, it freed up painters to become abstract painters, right? We didn’t need to represent the photo reel anymore. Well, when CGI got started, it was this race to the photo reel and we as a society have achieved that. Now we turn to the question of well, what can we use this technology for that hasn’t been seen before, that it hasn’t been represented before. We’re fortunate to stand on the shoulders of the giants that came before us and now abuse the technology to make it look nothing like photo real vut we have all that power behind us and all that knowledge.

BTL: Can you talk about working with the trio of directors: Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers, and Justin K. Thompson? How’d their visions unify or inspire you two?

O’Keefe: Oh, yeah. Fantastic trio. We’re blessed to have three directors in this case. It’s such a ginormous movie, that it really takes a lot of just excellent people in every at every level. Each director has their own specialty and special skill set from their years of previous experience, Kemp is a fantastic writer and so he could be working a lot with the story. Joaquim might be the best storyboard artist in the business when it comes to—for my money. His understanding of camera angles, pacing, and storytelling is fantastic. And then of course, Justin K Thompson, our guru, as the production designer on the first film, not only just has an incredible eye for what films look like and layout and camera, but has such an intimate knowledge with the filmmaking process here at Sony, that he was able to really drive and get the most out of the machine in that regard.

As well, I think it’s it’s always great to have collaborators at every level. And so for the directors to be able to collaborate with each other as well as—I have now three directors I can go to with ideas and get answers and we can all kind of come to these creative solutions and ideas together creates a really exciting space to work in. Again, it’s a highly collaborative medium and as a result, it’s just great to be able to work together with all these different people.

Gordon: Yeah, besides the fact that they each had their specialty, all three would contribute throughout the film. It wasn’t as though they were completely siloed off and only dealing with a certain area. They had these strengths and so they put a lot of time into that. But they would all contribute ideas, story ideas, visual ideas, editing ideas. You kind of got a richer brew having the three of them together.

O’Keefe: Yeah. I think each of their specialties sort of lends itself to their approach, not necessarily the work that they were doing but their their skill set and knowledge. Like I say, you’re never going to find the best writer, storyboard artist, and visual director all in one. We need three of them and they can all make the film together and they can unite their superpowers.

BTL: What about Phil Lord and Chris Miller?

O’Keefe: Oh, they’re fantastic. At the end of the day, they’re the kind of powerhouse creatives. They have brilliant sense of humor and storytelling. And I think, above all, the thing I appreciate that they bring to the table is an understanding of the audience and what ride we are putting the audience on. Their ability to sort of pull back from the film constantly and say, That’s a great idea but what if we execute it like this because this is where the audience is going to be, they are going to need a moment of levity here. This is when we’re going to bring in that emotional moment. They have such experience from decades of TV and film, and different mediums, live-action, animation, TV, all that stuff, that they truly understand the audience and how to tell a story that’s going to be entertaining. It’s seen in these films where not a second is wasted and a lot of that comes from their supervision and knowledge as filmmakers.

Gordon: Yeah, I think for me, the fact that they’re actually involved in writing the story so this is literally coming from them. It’s their baby in that sense. As we produce artwork, I mean, kind of a universal theme is they always want more. They always want to push it further, can we get the most extreme version of naturalism and to get the most extreme version of something being stylized and sort of not being satisfied with the first answer or the second answer but really driving to get to a new place. I really appreciate that drive because it’s easy to settle early on. I think one of the reasons the movies look so good is that they don’t settle early, they really push to get to a better place artistically and story wise.

O’Keefe: You can’t understate the value of having people at the executive producer level that are that invested in the film that they will go to bat for artists and say, we need more time, we need more resources to push this thing to the height that the artists are aiming for. That’s a rare thing in this industry, that people have that seniority are looking out for their crew and to protect the ideas of the film.

BTL: There’s been a lot of discussion about A.I. and using it for film and TV. How do you respond when someone like Jeffrey Katzenberg says that a blockbuster animated film can be made with 90% less cost, less people in as little as the next 3 years or so?

O’Keefe: My question to him would be like, “Why? Why would we want to do that?” As we’ve said over the course of even just this interview, I mentioned collaboration several times. I’m not looking to collaborate with less people, nor am I looking to make movies faster. I love making movies. What is this race to the bottom all about? So we can turn out a movie every minute and then not—what are we doing as filmmakers then? What are we doing as artists with our time? Let’s use A.I. to enrich our lives. I think the enrichment in our lives is through for us, I’m sure, all of us, it’s for the creation of of art and exploration. You might be able to tell an A.I. to make a movie right away but the big thing about these films and I think why they become so universally successful is because we spend that three years or whatever it is discovering the film together as a crew and discovering about ourselves and discovering about our characters and the stories we want to tell.

We don’t have all the answers when we start and that journey of discovery, to handing that all over to an A.I. and having it done over a lunch break just seems boring to me.

Gordon: Well, it’s actually terrifying in terms of job security but I have a feeling A.I. is going to become a tool like every other tool. I mean, it’s a unique tool, obviously, but a computer became a tool and I think we felt threatened by it when it came in. But now, we all will work on it. We’re very comfortable with it and we’re kind of glad with the tools that gives us. I have a feeling A.I. will become like that. I think kind of like what Patrick’s saying, I don’t think we want it to take over and just run things but if it can get integrated into the process, we ought to become adept with it. I think it could probably push our visions, but obviously the visions need to come from the people first.

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is now available to stream on Netflix.