The crowd goes wild. Composer Gustavo Santaolalla just finished playing “All Gone” and the main theme from The Last of Us at the Hollywood Bowl, and the crowd responded with passion. It was at the Game Awards Concert where Santaolalla performed just a sliver of his iconic work, his joy infectious and radiating off the stage all the way to the back of the Bowl.

It’s the same palpable delight for performing that helped Santaolalla land an Emmy nomination for his music for The Last of Us. The Oscar-winner, of course, scored the games and returned for the post-apocalyptic HBO series. “I’m honored to be nominated by the Television Academy for my work on The Last of Us,” Santaolalla said in a statement. “Emotion was at the heart of the score, driven by the vision of Neil Druckmann and Craig Mazin and by the power of this amazing story. I’m grateful to Neil and Craig for taking me on this magical journey.”

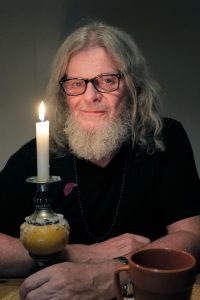

The artist is on quite a journey at the moment, given his wide array of projects in development and his ongoing tour. Recently, the composer behind Brokeback Mountain and Babel took the time to talk to us about everything he’s working on, his history with The Last of Us, and embracing chaos and mistakes as beauty.

[Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and length]

Below-the-Line: What are you working on at the moment?

Santaolalla: I’m working on a whole bunch of stuff. I’m working on two feature films. One is called Norita and it’s a documentary about the head of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo. I don’t know if you’re familiar with the Madres de Plaza de Mayo movement of Mothers that was created around the dictatorship in Argentina looking for the disappeared kids. I worked with mothers for many years now and abuelas because their grandkids, also, were kidnapped by the military rulers. This is in the ’70s where I had to leave Argentina, too. In 1978, I left Argentina.

We had 10 years, like a decade, in which 30,000 people disappeared at the hands of the government. So, there was this strong movement that was created by the mothers of the disappeared. It’s called Madres de Plaza de Mayo. Plaza de Mayo is a plaza, square that is right in front of our White House, which in our case is a pink house, but it’s the government house and they marched every Thursday around that square with pictures of their kids and with a white handkerchief on their heads. Three of them were taken and killed by the government.

It’s a very, very dark part of our history but it’s still going on because there are 500 kids that were kidnapped and raised sometimes even by the captors of their parents, and we have recouped 200 and something of them. I mean, people that have gained their identity. So, it’s a documentary about Nora Cortinas, that’s her name. She’s the head of Madres de la Plaza de Mayo. I’m also working on the first movie by Rodrigo Prieto, the director of photography that did the four films that I did with Alejandro.

BTL: He’s incredible.

Santaolalla: He also did Brokeback Mountain. He was the director of photography and he’s been working for the last 10 years or more with Scorsese. So, this is his first feature film and it’s based on an iconic book of Mexican literature called “Pedro Páramo.” It’s a big thing. It’s tapping into a classic of Mexican culture ,and this is his debut as a director. I’m working on a new Bajofondo album, as well. And so, this is our fifth album and we’re doing a fully electronic album. This is really, really interesting and a departure for us.

BTL: All great things.

Santaolalla: And working on a celebration of my album Ronroco because next year, between this year and next year, the album, it’s celebrating its 25th anniversary since it came out and that album, Ronroco, is the album that opened the doors for me to the movies with The Insider and with Amores perros and then Motorcycle Diaries and even The Last of Us. The Last Of Us theme is written in the Ronroco, in that instrument.

BTL: So when you’re working on all projects, what kind of creative space do you like to create for yourself?

Santaolalla: It’s very chaotic. It’s very chaotic but it’s just like nature. Nature is chaotic. Somehow everything falls into place and that’s how I see it. Aside from these things, I have other projects. Like, we have a small wine project in Argentina and a small book publishing company. All these things, I never do one thing that I started and I finish it. I work a little bit on this, then I move and I work a little bit on this. It has two advantages. One is that it doesn’t let me get so obsessive, which is the way I used to work many years ago when I was much, much younger than now. I used to just work on one thing. My life was 24 hours a day, one project. I found out that level of obsession went against the project, against me, and even the people that I had around me. It ended up being something bad for the project itself and for me. So, this way I’m always fresh because I never get so obsessed. I move to another project. And then, when I return to that project…

BTL: You have fresh eyes?

Santaolalla: Not only I have fresh eyes but also, there’s always something that I picked up along that journey through the other projects that, somehow, they cross-pollinate. They could even be different disciplines. I might be working on a movie and there’s something there in the movie that it ends up being translated in an album. It triggers something.

BTL: So, it’s a good chaos?

Santaolalla: It is chaotic but I always say, “Once I told you all the things that I’m doing, those are just words.” But then, the good thing is that I can then prove to you all those things that I’ve said to you, and this has been happening for years, that I will say. And then, the books are there. The wine is there. The album is there. The movie is there. The video game is there.

Even in the chaos, there is a sense of order, but it’s pretty chaotic. Things come up that you haven’t planned. It’s like, I don’t know, you get a flat tire. The musician didn’t show up or something. But that’s why I love quantum physics too, the principle of uncertainty. The only certainty that I have is the certainty of uncertainty, that anything can happen. If you are open to that, then it’s like a dance.

BTL: I have so many follow-up questions. When you were working on HBO’s The Last of Us, how did those other projects maybe help inspire you?

Santaolalla: Well, there are many, many things because first of all, in the process of the TV show, it was different than the process of the game itself because when we arrived to the show, the music was created already.

One of the things that I love that [Naughty Dog co-president] Neil [Druckmann] and [creator] Craig [Mazin] said in a few interviews that they thought that my music was part of the DNA of The Last Of Us, like it was another character. It would’ve been ridiculous to put out The Last Of Us, the HBO series, without Ellie (Bella Ramsey). So the same thing without “All Gone” or without those things because those are part of the story.

When we got to the show, it was different than when I had to create that music in the first place. The creation of the music in the first place was very connected to the way that I’ve been already working in movies. The way I work in movies is not the conventional way.

BTL: How so?

Santaolalla: The conventional way in the industry is that the composer comes at the very end when the movie is already been filmed, edited, and temped with other music and then the composer has to chase the temped and try to do something that is like that but not exactly so it’s not plagiarism.

I don’t work that way. First of all, I’m not a academically-trained musician so I don’t know how to read or write music. I come from another avenue. I like to work from the script and from my conversations with the director. Actually, lots of the music of any project that I’m involved with, it gets done prior to filming.

BTL: For example?

Santaolalla: The biggest example is Brokeback Mountain because the whole score was done prior to anything being shot and, of course, it was Ang [Lee] that decided what was going to go where. That was his genius.

So when I arrived to The Last Of Us, it was the same procedure because, as you know, in video games, the last thing you do is the rendering of the things. At best, you get a couple of drawings of the characters but you really are working, inspiring the story and your relationship with the characters. And so, that’s what was the process in that first game. Then that somehow continue in the second one with some additions of timbers, like the banjo and the lower octave classical guitar.

And then, when we got to the series, that universe was already created with all those themes now readapted. I always have said that I’ve never felt that I was writing the music for a video game. I always felt that I was writing the music for a great story.

I think a great story can be done as a video game, as a puppet show, as an animated project, as a theater piece. You can do it in any way like a Shakespeare story. And so, it’s not really a remake, the HBO series. It’s another way of putting that plague on stage. I think one of the different things, and the thing that allowed me to do my thing with this project, was that this was not the typical video game. I’ve always been interested in anything that music could play a part. I mean, I’m working on a musical too now.

BTL: [laughs] Of course you are.

Santaolalla: I’m a terrible gamer. I’ve never been good at playing. But we have a son, that at the time that I started working on The Last Of Us, was in his mid-teen years and he was a really good player. When I watched my son, I always thought, if somebody wants to connect with a player in an emotional level, in a more deep heartfelt connection, it’s going to be a revolution.

After the Oscars, after I won those two Oscars, I was approached by several companies for to do video games. One very important company, a French company, made a big offer and I knew that it wasn’t what I wanted to do. It was more of the same. Good projects but not what I wanted. When I met Neil, and Neil told me this story and that he expressly wanted to create that connection, I knew that that was the one.

BTL: The game was 12 years ago, and I imagine creatively, you were very different then. How have you evolved as a musician, and as a result, The Last of Us as well?

Santaolalla: Well, you have keep in the sense the characters but also get somehow reshaped. There’s the Joel of the game and Pedro Pascal’s Joel. But in a way, Joel keeps on expanding in different directions but it’s always Joel. I had to keep that, what I think was part of the language, not only in the themes in the melodies or whatever but even in the sonic fabric of the score and adapt to certain protocol that is seen on TV is different than in a video game, of course.

In this case, I felt more like if you will do a classical piece in a way. I go back to Shakespeare. I didn’t think I had to modernize what I was doing. I thought the task there was, even with the changes, that would’ve happened in me to try to keep true to what was the original feeling of that creation, you know what I mean?

BTL: A great example of maybe going classical instead of more familiar is in the season finale when Joel is going to rescue Elle and there’s gunfire, but the score sounds like the heart is breaking. The music screams drama, not action. It’s internal music.

Santaolalla: Internal music. All those little differences of when to put the music, when to stay out of the scene, when to make the music not external and when to make it an internal thing against something that you’re seeing. I mean, that contrast, those things are things that we pay a lot of attention with Neil.

BTL: What was it about that initial instinct that felt so right to go minimalist for the story? We don’t usually expect that from post-apocalyptic stories.

Santaolalla: Well, there plays a role of using your tools to the best of your abilities because, of course, if I want to and I make an effort, yes, I can get a full orchestral score, but I just don’t think it would fit that. It never came to my mind to. The Last of Us is something that’s so raw. Neil was interested in that aspect of my composition, my way of working. I mean, I’ve done Book Of Life with 90-piece orchestra or Finch with a 70-piece orchestra.

In all of the scores anyhow with orchestra or without orchestra, and Brokeback is just like a 40-piece strings but the guitar is there, my presence is there because I play in the score. I think that’s something very different. I’m not saying that this is better or worse. I’m just saying it’s different in the sense that usually a composer writes something, puts it on the stand, and somebody plays it and usually they’re fantastic players. But there’s something about when somebody that wrote something plays. It’s the same thing with a singer-songwriter.

When somebody who wrote the song sings that song, there’s something about it and that presence is very strong. And the way I use it, for example, the use of the noise, one of the things if you go to a recording, you’ll see that every guitar player and the engineers are always trying to avoid any noise that is around the guitar, the movements in the hands and stuff. I treasure those noises. I actually try to enhance them. Those noises is what makes them…

BTL: More human?

Santaolalla: Human and it gives this raw thing, this En Carne Viva. It’s like your skin just pulled out. I think the story called for that.

BTL: Talking about the perfect imperfections, what are those beautiful mistakes in The Last of Us score?

Santaolalla: There are many. One of the pieces in the banjo, that actually, there’s a run through the neck to get to the next part. I love it but I don’t remember now the name of the piece. I’ve always talked about the importance of the mistakes and so forth. I have a great story [about this].

BTL: Please, do share.

Santaolalla: When I came to this country, I distributed some of my music to publishers and only one guy responded. And so, we had a meeting. I brought my guitar. We listened to the music that I sent to him. Then I play some stuff. He said, “Well, listen, you have a great voice. I mean, your music is great, but there’s something in all the songs that you do… The songs are going great and there’s a moment that you seem to hit the wrong chord. You seem to hit the wrong note. I went, “Well, probably this is going to result in us not working together, but I tell you, that I take this as a compliment because I am looking for this point of inflection, this sort of mistake.” For many years, on occasions where people will say, “Oh man, what a weird chord,” I will say, “Well, a man once told me this and that and that.”

30 years later [after that meeting], there’s a tribute to Neil Young, a big dinner for the Grammys and stuff. I’m with somebody and he says, “Come on, I want to introduce you to somebody here. At the time, with Bajofondo, I was looking to do a collaboration with an artist that this guy, the same guy that I was telling to you about, that he represented. He knew me as the guy of the two Oscars, looking for Bajofondo to do this [collaboration].

So when this guy comes and introduced me to him, he goes, “Oh yeah, Gustavo, the Oscar guy.” I say “No, no, no. You don’t remember me but I know you used to have an office at this place and you told me something that has been with me since then.” The guy gets sort of nervous, but I say to him, “You told me that my music was great. My songs were great but at certain points, I seemed to hit the wrong note. When I met Anne Hathaway, which is one of the actresses of Brokeback Mountain, she told me, ‘When I heard that first thing and you hit that dissonance, I thought this guy’s a genius.’ You see the circle closed, and now people like that wrong note [I hit].” I’ve never actually felt resentment toward the guy or anything. Actually, it was the only guy that…

BTL: Made you feel seen for that?

Santaolalla: Yeah. So, we lost each other [at the event]. There was 2,000 people there. He came back with his wife because he wanted me to meet his wife. His wife said he couldn’t stop talking about it. I can’t imagine the guy thinking, “Boy, I could have signed this guy who won two Oscars and I told him that he hit the wrong note.”

It’s that moment in Amores perros, and that dissonance there. Although I don’t know how to read or write music, I have more or less some concepts. It’s, I believe, a seven major or something like that. Instead, it is opposite in the sense it is one note close to the other one but in an octave of difference.

So in a way, they are two notes that are so close and yet they’re so distant from each other, and I play around with that a lot. That’s the dissonance that I use quite a bit and I use it also in The Last Of Us. I feed myself on that stuff. I love it.

BTL: An experience you have as a composer is you’ve played live and seen an audience react to your music. How has that helped you as a composer when you’re working on films and shows?

Santaolalla: It’s amazing because I am convinced that the artistic experience gets completed by somebody exposed to it. That’s when the work gets completed. It’s just like in quantum physics, too. Things behave differently when they’re observed, and that’s what we perceive as a reality. We create reality with our observation.

I’m going to give you a perfect example. I can be for a week working on a track in my studio, putting the guitar there, the bass here, or this and that. Then after a weekend, a friend comes and I go, “I want to play you something.” You play the thing and suddenly, you are listening with that person without saying anything and suddenly g, “Guck. The guitar’s a little loud. I never heard [that before].” You hear differently now because you’re listening with somebody.

I have shared this with directors. It happens the same to them when they’re playing a scene to somebody, and they see something that they haven’t seen before. It is when you get a consensus, in general, that everybody kind of sees the same thing and hears the same thing, that’s when you get something that really is happening.

The work gets completed, really, by the audience. Of course, playing live and getting that music with the other people participating takes the music to a totally different place, for you as a composer and a performer.

The Last of Us season one is now available to stream on MAX.