Jane Premiere 2017. Photo Credit: Amber Connelly.

Perhaps more than any individual in global history, Jane Goodall has brought due attention to the preservation and survival of the planet’s diverse species of animals in their natural habitats. In the new documentary, Jane, directed by Brett Morgen, a combination of archival footage and new material illuminate Jane Goodall’s methodologies, values, and care for chimpanzees.

At the Hollywood Bowl last fall, the film’s producing entity, National Geographic, a critical factor in Goodall’s research and preservation projects, created a historic premiere of the documentary, now being considered as Best Documentary Feature for the 90th Academy Awards, while offering a figurative and literal stage to Goodall’s many supporters and admirers.

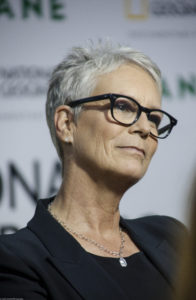

First down the red carpet was actress Jamie Lee Curtis who spoke of Goodall’s proud legacy being felt today. “She changed the way we thought, about the relationship between chimpanzees and us,” Curtis professed. “She went there and lived there and studied them and only allowed cameras when it was like, ‘Ugh: fine.’ I love that aspect of her story.”

Actor and activist Ed Begley Jr. noted how Goodall’s impact is both widespread and necessary to the comprehension of the human life cycle. “What she did in the course of human history of understanding the animals we share this planet with,” he said, “and how we’re not so separate from them—in our DNA, or our ability to have a language or to make tools—she discovered that, and she’s an amazing woman and a dear friend.”

Multitalented performer Alex Meneses offered an upbeat modern take on both Jane the person and Jane the film. “She’s true girl power,” Meneses quipped. “She’s one of the first people—primologist, anthropologist, conservationist—to put it out there and devote her life to it.”

Following the many supporters of Goodall and her efforts, the filmmakers appeared on the red carpet to support and discuss the film. Composer Philip Glass noted how his score came to him relatively quickly given the power of the images in Jane. “I didn’t try to get in the way of the music,” he said. “The music that came, I trusted it and I looked at the film—and I thought, ‘If I trust the material, I’ll be okay.’”

Glass’s score, which was replicated live onstage at the Hollywood Bowl by the Los Angeles Philharmonic while the film appeared on overhead and side screens, took only five days to record. “A good orchestra can do that,” Glass explained. “We’re in Hollywood, and these players know what they’re doing. I started in January [2017], and my part was over by the end of April. In fact, I argued for less music, because if you have a little less music when you hear it, it has more of an impact.”

Oscar-nominated Brett Morgen, Jane’s director, divulged that he attempted to create three intersecting narratives in the documentary. “One was a modern retelling of ‘the Garden of Eden,’” he revealed. “From the moment Jane steps foot there, it will never be the same, so the film travels that arc. It’s also a story about female empowerment. I wanted to make a film in which the hero who transcends the human realm was a woman. I felt it was something that was necessary, and wanted to turn my attention toward a subject that would provide those opportunities.”

Over a two-year period, Morgen sifted through 16mm film footage of Goodall, now 83, from long ago, largely shot by her eventual husband, Hugo van Lawick, coverage which he described as “mind-blowing.” “Most people think of documentary as providing us great access to lives and cultures that we otherwise wouldn’t have access to,” Morgen offered, “but for me, one of the great perks of this vocation is the opportunity to work with my own heroes.”

Case I n point, Glass was among Morgen’s moviemaking heroes, and bringing the composer aboard the project was a dream come true. “This film was created and designed to be a cinematic opera,” Morgen related, “and as heavenly as these images that Hugo created are, it needed the voice of God, if you will, and Philip does that better than anyone.”

Lastly, Jane Goodall herself spoke of the importance of the documentary as a reflection of her many decades of commitment to her cause. “I hope that people will be very moved by how the forest wasn’t being destroyed back then—chimpanzees were living in a wild, free home,” she said. “I hope that people will be inspired to want to help bring that back, and I try to give people hope that we can change things and try to focus on the amazing projects going on around the world. So, I hope that a lot of people will come away wanting to do their bit to protect the planet.”

Speaking about the relevance of chimpanzee behavior to mankind’s own self-comprehension, Goodall ended by noting the symbiotic relationship between humans and other mammals. “I would like people to understand that chimpanzees are, in a way, like ambassadors to the animal kingdom,” she conveyed. “They have helped science rethink our relationship, not only with chimpanzees, but with other animals, and that’s because they are so like us, and that science had to admit we are not the only beings with personalities, minds and emotions.

“Science has finally come out of the box it put itself in,” she added. “I think a major contribution that the chimpanzees have made, and, what is it that makes us different—because we are different—and we have all this technology, and Hollywood Bowls, and movies and I think it’s the explosive development of our intellect. How bizarre that this intellectual species is destroying our planet, and we need to get together and make things different. I hope this film will inspire people to join together to make that happen quickly.”