While British troops are trapped with their backs to the sea at Dunkirk by the advancing German army, Prime Minister Winston Churchill (Gary Oldman) faces his Darkest Hour – whether to negotiate with Hitler for peace or go to war with Germany.

While British troops are trapped with their backs to the sea at Dunkirk by the advancing German army, Prime Minister Winston Churchill (Gary Oldman) faces his Darkest Hour – whether to negotiate with Hitler for peace or go to war with Germany.

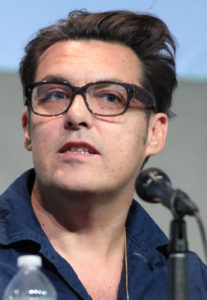

Director Joe Wright wanted to work on a pure drama and likes making films in England. Often the scripts there have a historical theme. Wright enjoys “the way we can see our contemporary world through the mirror of the past. Almost like fairy tales, it’s a way of exploring our emotions and responses to the world through the abstraction of the past.” In reading the screenplay for Darkest Hour, he said, “I laughed, and I was very moved. I cried, and I was shown an angle of a piece of history that I thought I knew. In fact, I discovered I didn’t know the whole story. To me that was very exciting.”

As he reads a script, Wright forms a vision in his mind’s eye for how the page will translate to the screen. Ideas start coming and he begins to obsess about them. He develops a need to see them realized. From the key, tent-pole moments that first capture his imagination, bit by bit, he continues to build ideas for the film.

Production designer, Sarah Greenwood is always the first key crew member that Wright discusses a film with. They have worked together for twenty years, since the first television job he did. He has only done one project without her.

“Sarah and I are totally simpatico; that is the key creative relationship of my career,” revealed Wright. “Sarah and I have journeyed together and loved each other for many, many years. She’s the first person I send the script to. Before I commit to a project I’ll ask her opinion and we’ll start discussing how we might realize it.”

The film has a defined visual style, with de-saturated colors, heavy contrast and deep shadows. Wright credits photo researcher, Phil Clark, as his “secret weapon,” who “trolls thousands and thousands of images.” Greenwood and Wright look at those images together, deciding what works best for their concept of the film, often based upon practical production problems they have to find creative solutions for.

Another of Wright’s regular collaborators was costume designer, Jacqueline Durran, who he has worked with on every film. The collaboration between Wright, Greenwood, Durran and cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel, was key to the film’s cohesive look.

Delbonnel was an exception to working with the same people all the time because Seamus McGarvey, Wright’s usual cinematographer, was unavailable. Wright admitted working with Delbonnel turned out to be “somewhat of a boon to the project.” Wright had met Delbonnel a number of years back and was a fan of the cinematographer’s work, so he was “honored that he would come and make this film with me.”

The team looked at photos and paintings together, discussing the fact that the film is set in May 1940, the hottest May on record, but they were going to be shooting in December and January. That particular limitation forced them into finding creative solutions they might not otherwise have thought of. They would need to create a sense of heat, but could not shoot outdoors, so almost everything had to be interiors.

“That started to suggest to us a kind of claustrophobic key atmosphere. As you are aware, the film is called Darkest Hour and there is a kind of darkness to it. We wanted something where the shadows were very deep, lots of rich blacks, but then this idea of extremely hard, very, very bright shafts of sunlight coming through small apertures and windows to create a sense of the heat, and contrast, and very dramatic images,” explained Wright. “These things kind of come out of exploring what the film wants.”

In the film, the interior of King George’s palace was actually shot in northern England. One of the problems with that location was that the filmmakers could not show what was outside the windows because that exterior would not work for Buckingham Palace. The proposed solution was to have the windows covered in the blackout blinds used to shield the building from German bombers. Greenwood designed shutters with small apertures at the top to let some daylight in. Delbonnel responded creatively by sending hard shafts of diagonal light across the frame, making the esthetic of the palace “something quite bleak, and something quite dramatic.”

Retired from the film industry and currently creating fine art, prosthetics designer and maker, Kazuhiro Tsuji, lives in a warehouse in downtown Los Angeles. The filmmakers managed to pull him out of retirement to create the prosthetics that transformed Oldman’s face into Churchill’s visage, helping the actor to inhabit the famous statesman’s persona. The mastery of the craft also allowed the director the freedom to shoot the film without imposing any restrictions.

“The amazing thing about that make-up is it did not make any demands upon how I shot Gary,” exclaimed Wright. “It’s all in camera. There’s no CGI work to fix anything at all. The process took about 6 months, maybe a bit more, of trial and error to achieve the sweet spot between looking like Churchill, but still being able to enjoy and appreciate the subtlety of Gary’s performance.”

Wearing all that silicon can be distracting for an actor. Oldman spent 3.5 to 4 hours every morning in make-up. Wright said the actor talked about how he just had to surrender to that process. Eventually Oldman was able to forget about it. The filmmakers did not see the actor out of make-up for about three months, so they soon forgot he was wearing make-up.

During actor Gary Oldman’s make-up sessions, the filmmakers started developing the rhythmic energy that Churchill possessed. Wright took a photograph of Oldman walking as Churchill that conveyed the prime minister’s dynamism and pace. Wright sent that photo to composer Dario Martinelli, who composed a piece of music based upon that photograph, which has become one of the main themes of the score.

“Dario composed the music for Pride and Prejudice, and we’ve never looked back, really,” shared Wright. “I bring Dario on very early into the projects. Way before we start shooting, I send Dario the script. Then we start talking about the music. In this case I was interested in this kind of political thriller pace.” Wright wanted the music to be minimalist, stripped back, with a good thriller tempo.

Before shooting began, Martinelli created three or four themes. Wright is able to play the music on set to help Oldman find the rhythm. The score was available to the cutting room from the beginning of the assembly edit, so temp music was never used during post. The film developed organically as a whole. “All these wonderful elements that we have to play with, you want them to always be speaking to each other,” commented Wright.

Every day after shooting, Wright would go to the edit room and give guidance on his intensions to editor Valerio Bonelli. They would review edited scenes and discuss what was, or what wasn’t working in a “very fluid process.” Before production, Wright tried to get the script as tight and “representative of the finished film” as possible. During production, he “shoots to edit,” without much coverage, and after production, he prefers to sit in the edit room shaping the cut, rather than giving notes and leaving.

“I believe in the process of making the film, of really rolling your sleeves up and crafting the film with the editor,” stated Wright. “For Valerio and I, it was about trying to achieve the right balance between the personal story and the political thriller. At one point, we went too far and lost too much of the personal story. It was that balance that Valerio had to hold.”