Last week, Roland Emmerich was doing press for his latest disaster epic, Moonfall, because that’s what directors do when their movies come out. And because modern film bloggers tend to ask the same questions over and over again, he was asked about the current state of the movie industry. Since he apparently does not understand the concept of irony, he decried superhero movies as being the singular things that are destroying it.

In other news, Tom Cruise thinks actors shouldn’t do their own stunts, and Shonda Rhimes believes soap operas are the death of TV. Also, irony is dead.

Roland Emmerich has built, by just about any definition, a remarkably successful Hollywood career by making the same disaster movie over and over again for almost three decades. Big, dumb action flicks that often revel in their own stupidity. His latest, for example, posits that the moon is actually a giant structure built by aliens, and inside is another alien artificial intelligence that is out to destroy all sentient life in the universe, so they knock the moon out of its orbit, sending it hurtling toward Earth and … zzzzzzz.

I saw the movie a few days after it opened, and my Six Word Review of it was, “Monumentally stupid. And yet, not unwatchable.” That could cover most of Emmerich’s movies, with more than a few of them not living up to the second part. I’m not saying the man is a hack, because he is obviously very good at what he does, it’s just that what he does is create mindless fluff. The film industry needs that, as does any creative industry, because not every movie can be Parasite. Nor should it be. We need the dumb stuff for one kind of entertainment, just as we need the smart stuff for another. Each also makes us appreciate the other more. It’s standard-issue synergy.

It reminds me of a great exchange from one of the seminal comedies of my youth, Caddyshack. The film’s main character, Danny Noonan, is a caddy from a lower middle-class home trying to get ahead in life. He thinks the way to do this is to kiss up to the man who owns the country club where Danny caddies, Judge Elihu Smails. As Danny is carrying the Judge’s bags during a round of golf, he laments that his family doesn’t have enough money to send him to college.

Smails’ response is a curt, “Well, the world needs ditch diggers, too.”

Roland Emmerich is a cinematic ditch digger. He knows how to tell a story and knows how to keep an audience engaged, it’s just that the engagement is with the lowest common denominator of storytelling — bombast and ham-handed pulling of heartstrings, with strained, expository dialogue and one-dimensional (OK, occasionally two-dimensional) characters. Sometimes, though, that’s just what we’re looking for. Moonfall fit that bill, just as Independence Day did a quarter-century ago.

For years, Emmerich earned millions for himself and his studio partners by making these movies over and over again. Big budget, cookie-cutter blockbusters that were exactly the kind of thing columnists like me were saying was a big part of why the industry was suffering.

I think it was me, actually. On another website. But since you probably didn’t read that, let’s revisit that notion just a bit.

Gradually, over the last 30 or so years, the studios evolved from movie companies that created all different kinds of films at all different kinds of budgets and in all kinds of genres, to blockbuster factories that only care about making movies that might be able to clear a billion dollars worldwide. Gone, for the most part, are the $20-$30 million romantic comedies that could net the company a profit of $50-100 million thanks to international audiences and inevitable streaming (formerly home video) revenues, as are the so-called mid-range dramas and thrillers, more thoughtful fare that could be made on modest budgets and become solid box office grossers.

Returning to that model, a studio could spend the same amount of money that it does on a single blockbuster and make more movies, and probably come out around the same place profit-wise when all is said and done. It lowers the risk, too, but then it also lessens the odds that one of the releases will hit the coveted 10-figure mark. So, y’know, pros and cons.

Point is, Emmerich’s brand of filmmaking has survived on the studio level precisely because of the kinds of films he makes. Which, even if they don’t have superheroes in them, are very much comic book movies. In the words of one of my idols, the late great William Goldman, comic book movies are ones with “predictable formula concepts that sacrifice richer stories for spectacle elements.” Boy, if that doesn’t describe a Roland Emmerich film, I don’t know what does.

These movies, by the way, don’t even make much money anymore. Moonfall was bodyslammed at the box office by the low-budget comedy Jackass Forever, which, while hilarious, is hardly high-brow fare. It was almost poetic witnessing Emmerich’s particular Hollywood witchcraft taken to the canvas by a movie featuring real-life disasters.

And yet, Emmerich decries the rise of superhero fare, despite the fact that the very success of the genre has helped keep him in business. Doubt it? Once the studios moved to the all-blockbuster, all-the-time model, it’s the superhero and comic book movies that have helped to keep the lights on. Also, and this is important, after a second straight year of devastating box office returns thanks to the pandemic, it was Spider-Man: No Way Home’s record-breaking grosses that tossed something of a life preserver to movie theaters across the land.

But Emmerich doesn’t like “capes,” and finds it “silly when someone dons a superhero suit and flies.” He also said, in the same interview, that Christoper Nolan is the boldest filmmaker out there, constantly coming up with original ideas and concepts.

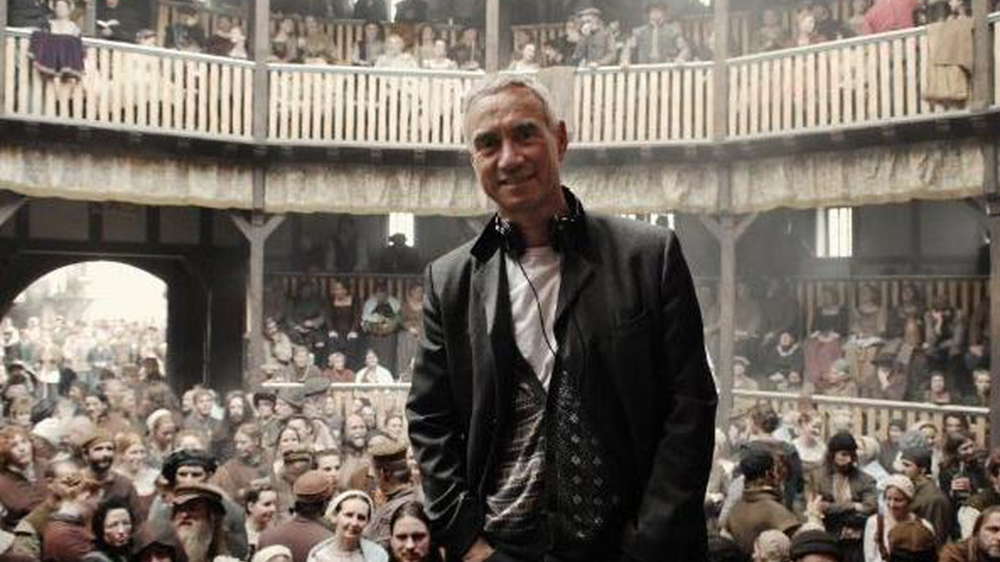

Christopher Nolan… who made his name with three Batman movies. Of course, Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy allowed him to tell more original stories going forward, just as Emmerich’s hits enabled him to go off and make the little-seen William Shakespeare drama Anonymous. and the LGBTQ-themed Stonewall.

Martin Scorsese, Ridley Scott, and plenty of others have also voiced concerns about what superhero movies are doing to film, and though I think they’re generally full of it as well, at least they have some street cred on which to stand. Emmerich really doesn’t, especially lately, when you factor in underperformers such as Midway, Independence Day: Resurgence, and White House Down.

Personally, I will go to great lengths to defend superhero movies, and when they’re done well, they elevate the action genre as a whole. They’re not just fun, they can actually make you think and engage you on a deeper level, and they can even be among the best movies in a given year. If you recall, in 2009, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences changed the number of movies that could be nominated for the Best Picture Oscar after a particular film was not nominated that year. That film? The Dark Knight. Featuring Batman. A guy in a cape. Less than a decade later, Black Panther earned a Best Picture nomination, and this year, pundits have made perfectly reasonable and even persuasive arguments that Spider-Man: No Way Home should have gotten a nod. The ultimate outcome of that fruitless campaign was sort of besides the point, as it was the mere thought that counted for something.

I have no issue with people who voice their opinion about something. Taste, like art, is subjective. What I have a problem with is people who denigrate an entire genre of creativity because they either don’t understand it, or have been excluded from it for one reason or another. I also take issue with those who bite the hands that feed them, and hypocrisy.

Roland Emmerich, with one opinion, has nailed all three. What a disaster, indeed!

Neil Turitz is a journalist, essayist, author, and filmmaker who has worked in and written about Hollywood for nearly 25 years, though he has never lived there. These days, he splits his time between New York City and the Berkshires. He’s not on Twitter, but you can find him on Instagram @6wordreviews.

Neil Turitz is a journalist, essayist, author, and filmmaker who has worked in and written about Hollywood for nearly 25 years, though he has never lived there. These days, he splits his time between New York City and the Berkshires. He’s not on Twitter, but you can find him on Instagram @6wordreviews.

You can read a new installation of The Accidental Turitz every Wednesday, and all previous columns can be found here.