A League of Their Own hit a home run in the eyes of viewers and critics alike, with the Amazon series earning raves for its acting, writing, and cinematography, as well as progressive storylines that Penny Marshall‘s classic film of the same name — which inspired the Prime Video show — couldn’t explore.

Also drawing praise is the work of Production Designer Victoria Paul, whose team crafted the physical universe in which the ladies of A League of Their Own live, play, unwind, and let their hair down — most notably, the stadium that the Rockford Peaches call home in 1943.

Paul’s 50-plus film and TV credits include Saturday Night Live, The Hunger, My Cousin Vinny, Lie to Me, The Finder, and NCIS: New Orleans. Below the Line recently caught up with her for an extensive interview in which she discussed her early days in the business before revealing the challenges and joys of stepping up to the plate for A League of Their Own.

Below the Line: Your road to film production design started with theater. Take us through what happened.

Victoria Paul: Everyone is different. I always made art, drew, and made things that eventually I called sculptures. I went to art school. My work started getting very presentational, like one point of view for the viewer kind of sculpture. I was living in New York. I had skill. I had a partner. We had a business building: built-ins, lofts, and custom furniture. I had that skill set. I was talking to somebody about it and showing them my art. They said, ‘There’s a place down the street. You should go. They would hire you.’ It was the Public Theater. I went there and said hello. They asked, ‘Oh, can you work in the shop?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ They hired me. I worked at the Public Theater, and it was awesome. It was when Joe Papp was still there. It was a long time ago, and an amazing moment.

Then, the guys at the Public Theater went, ‘There’s a school for this.’ NYU, the design school, was still over on Sixth Street at that time. It wasn’t at 721 Broadway. It was basically in an unheated hovel across the street from McSorley’s. I went over there and I talked to Lloyd Burlingame, who was the head of the department. And it was amazing. It was really wonderful. By the time I was done, which I think is true for most of the students who went there — during the years I was there, anyway — I established relationships with a lot of Broadway designers and was working as an assistant on Broadway. I thought, “Oh my God, this is fabulous.” It was a big canvas. A huge group of collaborators putting on a Broadway show is a fascinating thing. Someone I’d worked with in that world needed help drafting for a show that was coming to New York. That was The World According to Garp. I did that, and I met Henry Bumstead, who was the dean of American designers. I started and didn’t look back.

BTL: You went on to work on such projects as Saturday Night Live and The Hunger. What did you learn from those early experiences as you climbed the production ladder?

Paul: SNL was a weekly trial by fire. We’d get scripts on Wednesday afternoon. There’d be a read-through of 20-25 scripts. Everybody wrote — the writers and the comedians. Everybody threw everything into the pot. There was a slight winnowing before the read-through, but usually, they read about 20-25 skits. There were four of us there, designers/art directors, because that’s what it takes to make that show happen. We’d go off and have dinner. We’d sit around and hang out. Then around seven o’clock, eight o’clock if we were lucky, nine o’clock if we weren’t. The director would come in and say, ‘Okay, here’s the eight we chose. This is what we’re going to do on Saturday.’ At that point, we’d start designing. It’s eight o’clock on a Wednesday night. The four of us would quickly write it all down on a board and divvy it up. ‘You do this one. I’ll do this. You do this.’ We just started pencil drawing. We’d get it done, call the car service, and go home. Hopefully, it was before midnight.

The next morning — this is like a little well-oiled machine — we all did different tasks. What I would do is take all the joints we generated just a few hours before and go to the NBC Scene Shop, which was out in Brooklyn. I believe it’s still out in Brooklyn. They had a big scene dock, and they had a full scene shop there. I worked with the guys and said, ‘Here’s what we can build. Can we pull this off?’ By noon, I was sending trucks back to 30 Rock with [the] scenery. Everything had to be on a truck and rolling by the end of that day. This is Thursday now. Thursday, we’d have a night crew whom we would talk to before we left to get some sleep. They’d stand everything up. We would come back Friday, and paint would come in. We’d start to paint and dress. We were still shopping. Dressing would start rolling in on trucks. Friday night, we would leave and our overnight paint crew would stay to finish floors that weren’t done. Saturday, we’d come back until rehearsals and run-throughs. Sunday and Monday, we would sleep. Tuesday, we’d hang out and do it again.

BTL: And it was a great lesson in…?

Paul: It was a great lesson about realizing that, at any given moment — as a designer — you’re faced with a handful of choices. Hopefully, you’ve winnowed out the really odious ones, but [are] faced with a handful of choices that are all equally good, but in different ways. “If I do this, then that’s that. Here’s the road.” The important thing is whether it’s a clock that only has three days on it, like the Saturday night clock, or it’s a clock that has 10 weeks on it, like a prep clock for a show, it’s still a clock. It’s still ticking. The point is to pick one of those choices and move on because every choice you make generates other choices. If you get bogged down anywhere, if you fall down a deep well somewhere, you’re either not going to get out or it’s going to take a while to get out.

BTL: What was your first project where you were credited as Production Designer?

Paul: That is such a good question. I think it was an indie film in New York. I don’t even remember the name of it. It was about a boxer. That was the first thing, and it was a long time ago. The funny thing about that was, I had just finished, the day before, a movie called Ishtar, as an Art Director. Looking back on what it actually costs now, it’s like, “That’s the craft service budget,” but in its day, it was notoriously over budget. It was nobody’s fault, but notoriously over-budget. It was like trying to steer an oil tanker in the ocean, to this little micro-budget indie movie in one day.

BTL: What is your general take on production design? Should moviegoers and TV viewers take notice? Should it be a character equal to what an actor is playing? And how much of that depends on the project itself since one size does not fit all?

Paul: For naturalistic drama, and sometimes comedy, depending on the kind of comedy it is, I think it needs to be an endoskeleton that just holds up and supports everything. I absolutely think that, in the world of Marvel — or stuff like that — you want it to stand up and wave flags because it’s not mimicking our natural world. That said, even when you are doing our natural world, the world you and I recognize when we walk out on the street, you’re still making choices about it. You’re enhancing and pulling back on some of it, and you’re pushing some of it forward. You’re controlling the palette like it never happens in the world. You’re also controlling the texture and the lighting sources. There’s always a myriad of work you’re doing that makes a natural or realistic world. It really depends on the project.

BTL: How did you step into the batter’s box for A League of Their Own?

Paul: Here’s this strange but true story. One of my oldest friends, a wonderful set decorator named Diana Stoughton — who is from Pittsburgh — calls me and says, ‘They’re doing A League of Their Own. It’s coming to Pittsburgh. You’ve got to design it, so you can hire me.’

BTL: The film is considered a classic. How much did you want to pay homage to what viewers remember from the original, and how much did you want to veer off in a different direction?

Paul: Part of it is the look was the look because the period is what America looks like in 1943. As far as paying homage to the film? We talked about some of that, script-wise. Will Graham, the showrunner, said, ‘Yes, we’re going to have the line (“There’s no crying in baseball!”), but it’s not going to be said by him.’ Will absolutely wanted to pay homage but never copy, because that’s its own thing. He and Abbi Jacobson (who stars in, co-created, and produces the show), actually went to Penny Marshall (shortly before her death in 2018) to make sure they had her blessing to do this. Our thing was different because it was through an utterly different lens. The story we tell is nothing like the story Penny did.

We both tell the story of baseball, of a disparate group of women coming together and actually forming a team that can play together … and win. The baseball story is the baseball story, but other than that, our story is very different. It’s a story they couldn’t tell. It’s a story about gay relationships, and how queer people existed in the world, how they had to be hidden. It’s also a story about black-white relationships. Rockford definitely had an African American part of town and a white part of town, and the two really didn’t mix that much. It’s a story about black oppression at that time, and how internalized it was in the black community.

It’s also a story about feminist oppression, because these women are supposed to fill the roles of wife and mother. That’s what their jobs were. It’s about them expanding what their possibilities in the world are. “I don’t have to be a wife. I don’t have to be a mother. I love playing this game. I can do it.” At the end, although a lot of it is — from our point of view – “Oh my God, wearing skirts?!” I actually think it has a real beating heart because it is about allowing these characters to understand their possibilities, to believe in what they can do, and then he gives them a chance to go do it. It’s wonderful. A lot of that reality from the scripts, showing gay and Black-White relationships, as well as deep, Black female friendships, was our touchstone for design. We wanted it to be a very real world. We wanted it to be layered. We didn’t want it to look glossy. We didn’t want any rose-colored glasses there. The reality in the scripts was our touchstone for how we built the world.

BTL: You basically had to build the main stadium as well. Tell me about that.

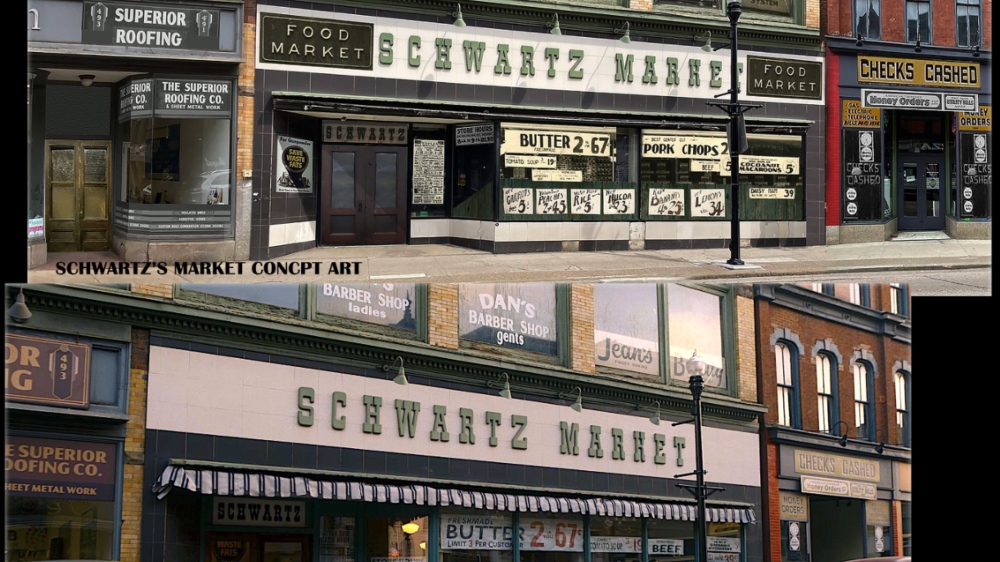

Paul: That was fun, but also nerve-wracking, because we were still in supply chain hell, and still are. The marching orders were to go to Pittsburgh, decided on a level above everyone’s pay grade. We went to Pittsburgh, which didn’t have a stadium. We were looking for stadiums of that era. We had a couple of things, including the actual Rockford Stadium. The pilot for this was done over a year and a half before we started because of COVID and a bunch of other things. In that time, and during the pilot, Will and Abby had amassed a trove of research, binder upon binder, which they handed to us. much of it written, some of it photographic. It was information about Rockford, factories, women working — every facet of that world at that time. The actual stadium the women played at was in Broadford. It was a bigger, concrete stadium. We deviated from that purposefully. We wanted the wooden look. But almost from the beginning, there was a horde of logistical issues we had to answer.

BTL: Including?

Paul: Our goal was to find a sweet spot where we could gather enough extras to do most of the stuff without having to replicate them and have visual effects shots every time you’re in the outfield, looking this way. We looked at a lot of different depths and sizes. We also thought about where we are going to be a lot. We’re going to be down the first baseline an awful lot, which is true, and going that way. We hit a number around 700, [which] is what we seated, the way the aisles worked. It’s pretty good because you could either fill a section of it up or — if you came back and did this — you could fill the first four rows so that you didn’t have to go to a VFX shot for a lot of it. The goal for us was to be as practical and real as possible, everywhere.

This is deviating from the convo about the stadium, but there are moments when I can’t do a shot of a street and take away every second-floor air conditioner. There was that kind of period-correcting clean-up that VFX did for us, but for the stadium, we wanted to keep it as real as we could with as many extras as we could muster. There was another tipping point where, if we had too many extras to keep up with, Trayce Field, the costume person, would say, ‘I can’t clothe 700 people.’ We never actually had a full stadium. It turned out that when we were in Pittsburgh, there was a wooden stadium in Quakertown, outside of Philly, about five hours away. Not really tenable. Then there was a little wooden stadium up in Erie. Again, four or so hours away. Both of those would have required something like us saying, “Okay, we’re going to shoot the stadium for three weeks. Let’s go there.” It’s not like we could go and come back. It was the distance. We were an episodic show. So, what are you going to do? Carry all your directors for the whole time?

Then there was the added surprise of the weather in Pittsburgh, which essentially was rain. Weather in Pittsburgh in the summer is rainy, which nobody likes. Anyway, it rained, but it didn’t just rain… it rained torrentially. There were days [when] there were five-hour lightning delays. We almost came away from almost every episode with no baseball, because not only did we not shoot, we generally couldn’t shoot the day after because the field was flooded. If you look carefully, there are moments where you’ll see the girls running and water is springing up the steps. We also couldn’t ruin Trayce’s clothes if they’d run in the mud. After going to a stadium that was only two hours away — a modern, horrible stadium — I actually figured out how to redesign it all, pull out the seats, do this and that. The cost was [higher]. Retrofitting that was more than if we built our stadium. So, then the next part of it was the hunt for a piece of land.

At first, we were hoping to find something that felt urban, that felt like it was a stadium in the city, or at least where we could see housing and just feel part of the city. We didn’t find any land big enough to support that, but what we eventually found was a baseball diamond that had 90 feet to the bases and about — I’m going to say — 380 or 385 to the outfield. It was a legit-size diamond and outfield so that we could have enough room for us to build a stadium. We did that, and we started from scratch. And when I say from scratch, the first thing we did was build a road so that we could get there.

BTL: How pleased are you with what we ultimately see on the screen?

Paul: I love it. The stadium, I’m really happy with the design of it. The design was, more than anything, an amalgam of all of those wooden stadiums, from Quakertown to Erie to Littleton Fields, that we all know out in Ontario and here in California. They are all of a type, and of a kind. I feel like it nestles into that well. I also feel like I had an amazingly talented team of painters who were out there — after we painted it for weeks — just aging and sanding. When we got there on the first day, that stadium felt like it was a relic not from 1943 but from some time in the ’20s. It was already well-aged by the time our team got to it.

BTL: Who was your secret weapon on the show?

Paul: Diana Stoughton and her team, the Set Dec team, were phenomenal people. Pittsburgh is not a place that has prop houses. You don’t just go to the prop house and get all of their contacts. They were kind of like, ‘Hey, I know a guy that lives in a little town.’ That’s how everything happened there. We did this set, the secret gay bar, which was a set I really love. I said to Di, ‘I need a long bar. I need 20 feet.’ She found a couple of things. They were 12 feet, and 14 feet. It was not going to work. Then we looked at a website. She knew of a guy who dealt in old, quite gorgeous bars. Gorgeous to the tune of $30,000, $40,000, and $50,000. Gorgeous, but not happening. Then she was talking to a hardware guy, a guy she knows from somewhere. He said, ‘I know a guy who has an old bar in his barn.’ Literally.

So, they drove out there, and in the loft of this guy’s barn was a 20-foot-long Art Deco bar and back bar. The front bar, as they pulled it out, a bunch of mice scattered. It’s mouse-eaten and all that, but they brought it back. It needed a fair amount of repair. Many generations of critters had called it home. The back bar had these curved glass neon lights on either side, and the glass tubes were intact. It was like, “Oh my God!” It took a bit of refinishing. We added some mirrors and picked wallpaper. We did a few things, but basically, it was from the loft of a barn in western Pennsylvania. That team was wonderful. The paint department and my art department were also great. Matt Horan, Nathan Ogilvie, Sam Kramer — they were all terrific. It was really good in that way.

BTL: How ready are you for another season?

Paul: I’d be happy to do it. From your mouth to God’s ears.

BTL: What is next for you, Victoria?

Paul: I just wrapped a show that’s as 180 from that as you could be. It was something I wanted to do because I just needed that other flavor. It’s called Twisted Metal. It’s based on a video game, and — I think — the last iteration of it was released 10 or more years ago. It’s basically dystopian future/vehicular manslaughter. We got to design incredible vehicles, and this was not a show where the place was a character. This was a show where every vehicle was a serious character. We got to design super-fun vehicles… build, age, and crash them. Hopefully, that’ll be available for viewing in the spring. That one will have a fair amount of effects attached to it.

A League of Their Own is now streaming on Amazon Prime Video.