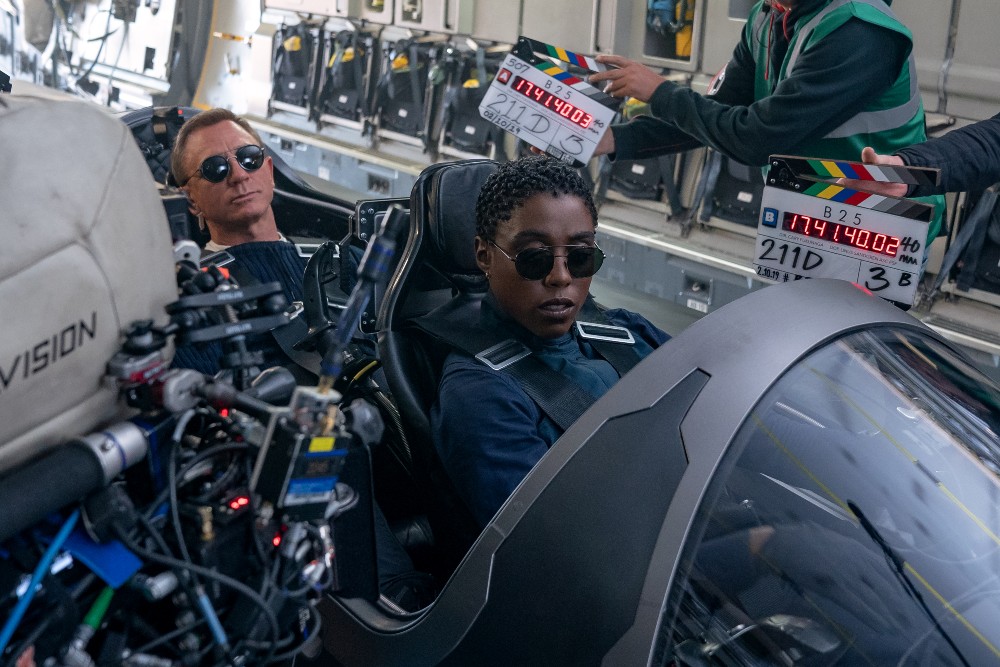

No Time to Die, the fifth and final James Bond film to star Daniel Craig, earned some $56 million in its opening weekend in North America. Directed by Cary Joji Fukunaga (True Detective), the story picks up from Spectre, the previous entry in the franchise with Bond and psychologist Madeleine Swann (played by Léa Seydoux) having retired to the medieval town of Matera, Italy, until her past returns to haunt them. The plot takes Bond to the Caribbean and Norway before he encounters the devious villain Safin (Rami Malek).

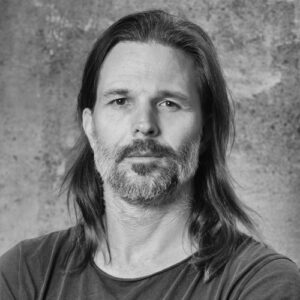

Oscar-winning Cinematographer Linus Sandgren, ASC, FSF, shot No Time to Die on film, with almost an hour of footage in IMAX. A native of Sweden, Sandgren recently worked on American Hustle and Joy with director David O. Russell, and since finishing No Time to Die, he photographed Don’t Look Up for director Adam McKay. Sandgren received an Academy Award for La La Land, directed by Damien Chazelle, and also shot Chazelle’s following film First Man.

Sandgren spoke to Below the Line by telephone from Los Angeles, where he is finishing work on Chazelle’s next movie, Babylon.

Below the Line: Can you talk about your decision to shoot No Time to Die on film? Was there any pushback?

Linus Sandgren: You have to have a reason why you shoot on a particular format. I think sometimes digital could be much better for certain reasons, but this was an adventure film that should feel rich. Both Cary and I felt it had to be shot on film to capture that environment. Barbara [Broccoli] and Michael [Wilson], the producers, saw that as well, so there wasn’t pushback at all, but rather support for our choices.

I’ve been lucky being able to shoot on film on basically every project I’ve done, so that’s my go-to. I love to light with color temperature, use that to create depth in the imagery. I can use film stock to enhance and make what you see is even richer.

I had a great collaboration with my gaffer, David Sinfield. I worked with him in London on The Nutcracker and the Four Realms, where we figured out color temperature shifts for different environments. Here, for the opening in Norway, the sequence was very cold and lit with a lot of contrast in colors. Then we go to Matera, a very bright location, and from there to a weapons lab. I thought, okay, after Matera, what do we cut to? Let’s make it night, because it could have been day in the lab, but night feels more mysterious and suspenseful. Maybe not night, maybe twilight, so the sky is dark purple and the city looks romantic, but rich, you know? It’s about creating that rich world that is a little more enhanced, and then contrasting that colorful sky with white lab interiors. No, let’s add a little cyan so it contrasts in a more beautiful way, then add yellow colors to contrast with the cyan. We tried to work that way all the time to make the movie a little more romantic, if you will, like romantic action.

BTL: How much of the film is IMAX? And do you have to frame differently for that format?

Sandgren: I think it’s about 40, 45 minutes in IMAX. The native format of 15 perf is 1.43 to 1, which is almost the Academy full frame [1.37 to 1]. But we frame in 2.40 because if you framed for TV, you would have the heads up too high. We regarded the image area above 2.40 as peripheral. IMAX was an opportunity to feel more immersed, engulfed in the film, have the image wrap around you. Tenet was shooting at the same time, so we had to work with that production to schedule the cameras.

BTL: Can you talk about shooting in long takes?

Sandgren: We tried to tell the story through a single camera, one that’s based on the emotions in the story. I think it’s a way to get the viewers to feel like they’re on a journey. They don’t always know where the camera’s going. It also means we didn’t need to cut to something, but rather pan or track to discover environments without editing. It brings a forward motion to the storytelling.

There’s one long take that’s handheld, where you can feel the pain and hard work it takes for Bond to get through a battle. It’s handheld because his emotions are unstable, he’s not in control of the situation. The viewers are also with Bond, almost like taking cover behind him, hopefully feeling what he is feeling.

For the guys breaking into the lab, the camera is much more precise, controlled dolly moves that are almost surgical. With Bond in those situations, we would be tracking with cranes or drones, some smoother movement. It’s nice to not have to cut around or shoot coverage and cut scenes that way.

BTL: You shot an action sequence set in Cuba that ranges over several floors and rooms before spilling out into the street.

Sandgren: We were going to shoot that sequence early on, but Daniel hurt his ankle. That changed everything in terms of logistics. We scouted in Cuba, but the scope of the scene made it impossible. We would have to shoot at night and keep that neighborhood up for six weeks.

So the whole Cuba quarter, the interior of the hotel and the exterior street, was an incredible build by Production Designer Mark Tildesley. It’s all on the backlot at Pinewood, with some small set extensions built at far distance. It was incredible to light, to figure out shots and stunts.

BTL: How much do you rely on pre-viz?

Sandgren: We use a combination of tools, we didn’t really nail down a number one, perfect workflow. Previz is just a communication tool, like storyboards. So the director knows that everyone knows what we’re doing, that everyone knows what to do.

For the most part the film was not storyboarded, but for action sequences with special effects, we used storyboards, or pre-viz, also 2D and 3D animatics. We photographed with miniatures, using GoPros to film cars moving on rails through environments to display or explain a way of doing things. The pre-viz would be used to help the second unit shoot exterior wide shots of cars for action sequences. We used so many tools, but everything was constantly changing so we were working until the last moment. We scouted and photographed and videoed ideas, it was a mix of things.

A lot of the effects in the film are in-camera. We shot a lot of the action with the main unit because we wanted to be close to Bond and Madeline, so the actors are in a lot of those shots. Of course, when a car is flying over rocks, that’s shot by the action unit.

BTL: How big was the production?

Sandgren: The scope was enormous, especially compared to what I’m used to. Bond films are the largest possible. Even a normal action sequence in another movie, here it takes place in an incredibly hard town to shoot in. Matera has like only two entrances to the town, you have to drive across a bridge to get there. Hilly, rocky, very narrow streets. The scope of just one day’s shoot was huge. It took hundreds of people to help lock up streets.

It’s incredibly luxurious to have the ability to go anywhere in the world to shoot. It was like, “Let’s do it in the most interesting town that could be both romantic first and then really hard for an action sequence.” There weren’t any limits for the production. It was fun to start with an icy, cold lake in Norway and go to a super romantic hideaway that suddenly turns hostile, a town where you don’t want to be in a car chase.

BTL: How involved are you with the colorist?

Sandgren: My goal on every production I do is have the final look of the movie on every day. That’s my number one goal. If that is not the case, I need to change the lighting or something. That’s why I like to work on film. When I get the dailies back, I can work very closely on the colors on an everyday basis.

I work with [Colorist] Matt Wallach — he did the dailies on Joy, La La Land, Battle of the Sexes, First Man. From Day One, he sends me high-resolution stills from the lab, which I look at on a color-corrected iPad. The dailies from those films were actually how the movies eventually looked. If something was wrong in the contrast or exposure, I made changes for the next day. For the DI, we really just go in and match shots to make them look like the dailies looked. Obviously, I may have to change the skin tone here and there, but the general look should be there in the dailies.

For No Time to Die, I told Cary I don’t understand why we do dailies, then have a completely different colorist for the DI. Ideally, I would want to have one colorist who controls everything, including the trailers. Cary agreed. So Matt did the dailies, he went to London for the DI, and he’s the colorist on the trailers.

When we did the DI, it took basically a week because he knew the film so well from the dailies. Maybe some exposure differences that needed to be evened out. I had a few other notes, but on the whole it was so quick. The same goes for Adam McKay‘s Don’t Look Up. I finished the DI for that while I was shooting this in basically three or four three-hour sessions.

I know some people will just shoot a movie and then in the DI, they sort of find the look or finish it. That never happens in my experience. No one wants to find another look than what they shot. It’s not how I like to work.

BTL: How does working with Cary Joji Fukunaga compare to a director like Damien Chazelle?

Sandgren: All directors are different. Part of the cinematographer’s job is to have your way of doing things, but be able to adapt to the vision of the director. David O. Russell needs a lot of flexibility on the day for improvisation, so you need to be prepared for turning the camera around. Be ready to shoot in a completely different direction.

Over the years, I’ve learned that the more I learn, the more I should start to listen to other people. If you think you’re right, you’re probably wrong, because you’re just doing it the way you always did it before. If you want to reinvent things, make them fresh, you need to consider the complete opposite from what you think is right. I remember Damien pushed me a lot on La La Land. He had big ideas I felt were never going to work. I mean, how were you going to move from there to there with a crane? That made me think about how to do it. Thinking outside my own box, we found solutions.

Cary was similar to that, always pushing you to think a little further. He was very much about maximizing the experience, maximizing the sets. He wanted always to extend the shot a little longer. When you finally come up with like a great idea for a shot, like how we drive down the road into Matera behind the car, and then the car takes the right turn, but the camera keeps going out over the edge to show the town — that was a very complicated shot that no one thinks about. We had a crane on a truck following the car, and we built an entire tunnel plus a set where we exit the tunnel.

Once we had that figured out, Cary was like, “Can we fly out a little further? Like five feet more?” Whatever you end up doing, he wanted more all the time. That’s his spirit.

Part of the joy for me is to learn how directors work around problems. It’s not always that what I think is the right way. So I also try to be open to see. Sometimes you need a director who has a completely opposite idea for what you think is the right way to do it.

No Time to Die is now playing in theaters across the globe. You can also read our interview with Editors Elliot Graham and Tom Cross, and look for our interview with 2nd Unit Director Alexander Witt very soon.

All photos courtesy EON Productions and MGM Pictures; Photographer: Nicola Dove (except where noted)