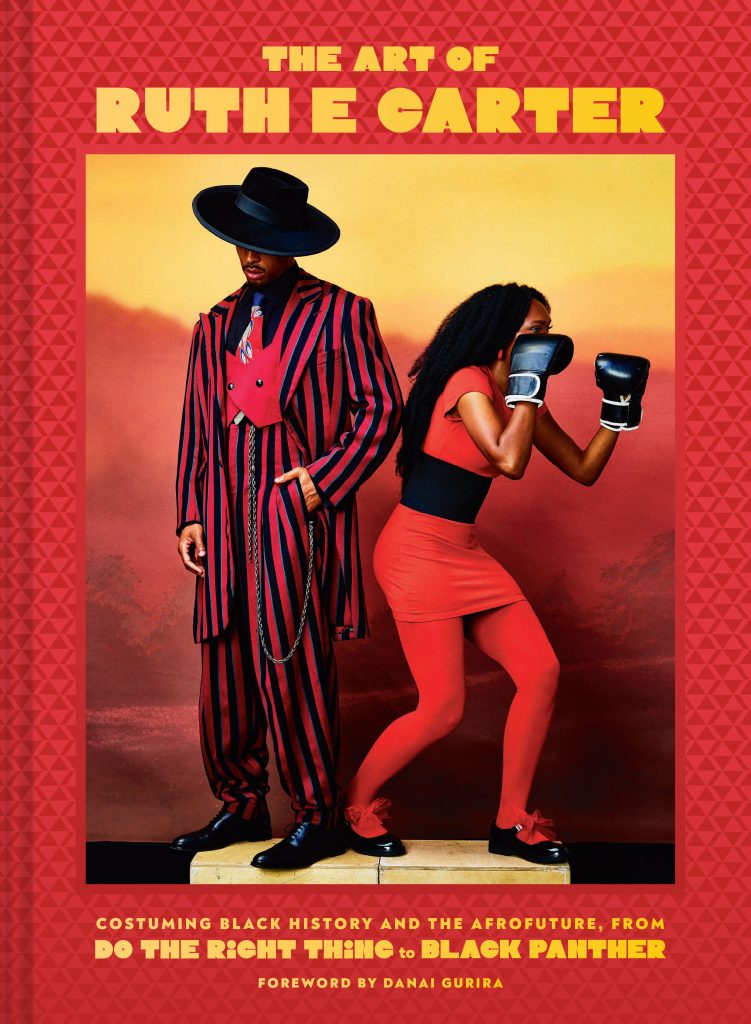

Where to begin with Ruth E. Carter? It’s a question I asked myself before interviewing her for her new book, “The Art of Ruth E. Carter: Costuming Black History and the Afrofuture, from Do the Right Thing to Black Panther.” Now, I wonder where to begin again as I write this introduction.

Let’s start with: Ruth E. Carter is an artist.

For years, Carter’s vision has inspired filmgoers’ imaginations, not to mention earned her two Academy Awards for her work on The Black Panther films. She’s the costume designer behind a long list of influential films, including several classic Spike Lee joints, Love & Basketball, Amistad, Selma, and What’s Love Got to Do With It.

With “The Art of Ruth E. Carter,” the titular author offers a behind-the-scenes look at her filmography, but not only that, an enlightening read for anyone interested in a career in the arts, whatever the medium. Filled with lessons for creatives, the book invites readers in to explore Carter’s process, where it started, where it is, and where it’s going.

To celebrate the release, as well as an upcoming signing and conversation at The Academy Museum, Carter spoke with us about her career and even read us a poem.

[Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and length]

Below-the-Line: Congratulations on the book.

Carter: Thank you.

BTL: I actually thought it was suspenseful.

Carter: Nice. What was suspenseful?

BTL: Oh, reading about School Daze and the obstacles you face on sets, like when you had to go search the dumpster for some of your costumes. You just have to deal with so many variables on every project.

Carter: You’re thinking on your feet about the things that are important to you, and maybe not to everyone [else], like you would want. I remember in my theater days, I came back the next year; all the work was dismantled and tossed aside and thrown out, and I was devastated. Intertwining two worlds of a theater girl entering the film industry and melding the two has had its positives and has had its struggles.

BTL: So, you say theater girl, but my takeaway from the book was also history girl. History was a major influence for you from the beginning, right?

Carter: That was my portal to understanding how to use this medium of theater or film and have a purpose in theater and in opera because I went to Santa Fe [Opera]. We were always thinking of theatrical things in history — doublets and Bucket boots — and we were making these wonderful historical pieces. I always thought I would love to do that for Black America.

BTL: An alternate title of this book could have been “Ruth Carter: A Story With Purpose.”

Carter: I like that.

BTL: Obviously, there’s purpose in everything you do, but it’s a word that comes up a lot in the book. It’s a broad question, but what’s your philosophy for purpose?

Carter: To tell the story in an authentic way. When I approach costume design and when it’s displayed in my projects, I felt a real sense of responsibility to be that conduit. To merge some of our greats in photography and our greats in art, to merge what their vision was in those times because it was real for them in those times — I feel that I honor the artists that I admired, that I looked up to, by using their work to create my own.

When I first got into costume design, even in college, I was doing “Style of the Blind Pig,” and I was doing literary greats work, [Lorraine Hansberry‘s] “A Raisin in the Sun.” You can’t take a work like that — a work that has been redone many times for its expression of a time and places for Black Americans — and not want to put your own spin on it, or your own signature to how you see that story playing out in history.

BTL: Even just thematically, do you feel like that just brings so much to the work, just keeping that present and past tied together?

Carter: It gives me joy. It actually does also help actors merge into characters because they want to come from a real point of view. They want to come from a real place. You can’t look at research and not be thrilled about possibilities. My purpose was an opportunity to show representation in our past and our present and our future.

BTL: Did you also want this book to be a gateway for people to discover those artists you admire?

Carter: Yes, it’s amazing. Sometimes, those artists cross color bounds. I looked at [Marcel] Vertès for Amistad, and there were artists that painted Blacks in art, and they would be a sub-character to the whole painting. I would look at these paintings because I had a two-volume set called “Blacks in Art.” It was a book that found those paintings that depicted African Americans in these great works of art, even if they were in the corner. I was inspired by that.

BTL: You wrote about your relationship with poetry and music. Do you think opening yourself to the whole world of art plays a major role as a costume designer and as an artist?

Carter: Yes, because everything works together. The vision is what’s important. Even if it’s music, I think of the storytelling in music by Curtis Mayfield or Marvin Gaye. Sometimes, I can listen to music of an era or even of a genre and be inspired, and I look through the research while I’m listening to the music of the time. I remember listening to Billie Holiday‘s music and thinking, “Wow, I can hear the pain, I can hear the struggle.”

When she sings about the [strange] hanging fruit, you hear more in her tone and in that song than you would ever read about just from looking at the words. There’s a lot of history there that’s interconnected. We can’t just stop at what people are wearing. We need to understand why they’re wearing it and what’s happening around them and all of that.

BTL: You have your own journey with your voice in the book, but on School Daze, you already had a confidence in your vision by then, right?

Carter: Well, I went to 40 Acres and a Mule with a background in theater. I knew how to break down a character. I went to my brother’s studio. He helped me do a budget and figure out point A to point B because this film was much bigger than any theatrical production I had done on my own. Once I made a roadmap for myself — whether it was at my brother’s studio or it was in the beginning prep at 40 Acres — I felt I could gather the clothing to get this whole thing done.

I knew about color palettes. I knew because I had been looking at my work on stage. I knew how to make one group feel like this and the other group feel like that. If they were to interconnect, it would look like something else. What I didn’t realize was how to compartmentalize my process and delegate. That was something that experience could only teach you.

I worked super hard, and I don’t feel like I was really always connecting to my voice as much as I was connecting to getting it done. What saved me was all of the prep work that I had done early on. I realize now that how you prepare really does keep you in line with the look that you’re going for, the voice you want to have, because it can get all discombobulated.

People come in and have certain needs. If you are trying to find yourself during all of that, you’ll never do it. It won’t happen; it’ll be fragmented. The more I can prepare myself for the journey, the better the journey.

BTL: Artistically, you had all that experience by your first film, but delegating was — and is — a major part of expressing your vision. On which film did you know how to make sure the voice was heard and stayed in a machine as big as moviemaking?

Carter: I think that I found [the voice] after Malcolm X, which came before Amistad and What’s Love Got to Do With It?, and I don’t think I can say I truly found my voice on Malcolm X. Although, because of the artistic freedom I had, working with Spike and having a relationship with someone who trusted me, I was able to implement a lot of my dreams of this movie without opposition. If the zoot suits were loud, and then it calmed down during this New York hustler phase, and then it went very monochromatic in prison with denim, just the blues and denim.

Then it traveled out of that phase into the ’60s for the Nation of Islam, and it became very black and white and contrasty. Then he travels on a Hajj to Mecca, and he has another mindset about Islam, and I was able to soften the color palette and soften his look. I was able to do that without any opposition. I feel that was a voice that I put to that film that worked.

BTL: Your films with Spike Lee are eye-opening for a lot of film fans, just showing them what can be accomplished with film, but it’s funny when you talked about that first meeting for Black Panther and the producer expressed how much your work meant to him, you were surprised. At a certain point, when did you realize your work spoke to a lot of hardcore film fans?

Carter: I didn’t realize it honestly, because I was working so much. I did two films every year for 20 years, and I didn’t stop to say, “Who’s watching? Who’s listening?” I knew that when I was at 40 Acres, he wanted something innovative from us. He wanted something that was going to be impactful from us. I think that it wasn’t until I was nominated did people say to me, “I didn’t know you did B.A.P.S.” “Oh my God, I didn’t know you did What’s Love Got to Do with It? You did that?” I thought, “Yes, you all didn’t know that? I’ve been here this whole time.”

I didn’t know if I really had a sense of the effect of the younger generation and their admiration for what groundwork we laid out for them. I really do think that between Robert Townsend and Keenan Ivory Wayans and Spike Lee, they were tilling the soil, and we were all a part of that. There was no Instagram, there was no social media, there was no sharing of like, “This is what I did. Look at this, I’m going to do this.”

I will say that 40 Acres always had that credo of let’s uplift the race and put more people of color, all colors behind the camera as well as in front, let’s have representation in both places. I was very conscious of representation. I had interns all the time. I really wanted to do my part because I was supported as a young artist. I did internships. I don’t know if the masses, especially people of color, realized that you could do internships in costume design.

I was an intern. I didn’t make any money for a year and a half after I graduated from college because I was an intern. I was in a position to learn, and I had to apply for internships.

The impact that that had on me to have a voice to be a costume designer, we were trying to implement that on the next generation. We were very much aware of that, but not aware of how that generation was actually going to use it and be that [next generation]. When I sat in front of Ryan Coogler, and he said, “I really admire Spike Lee’s films, I grew up watching your work.” I was like, “Wow, there it is. There is our intern out there in the world learning from us.”

BTL: You’re continuing to do that work. Speaking as someone who’s done interviews for a while, I hear all the time from young artists, “I didn’t know I could do that as a job.”

Carter: Do you think that Hollywood kept it a secret? It’s hard to imagine that Hollywood’s in almost its 100th year, and people are saying, “I didn’t even know that was a job.” Now, the Academy is working at being supportive of the independent filmmaker and the schools, and they want to be at the HBCUs with a voice and saying, “Hey, hey, hey, we’re here to give you mentorship, to show you how this is done, and to let you know that this is an avenue.” Because I still don’t think that a lot of people realize they can make a living doing art.

BTL: I’ve seen a lot your work, of course. But before this interview, I did watch a film of yours I hadn’t seen before: B.A.P.S.

Carter: Oh, nice.

BTL: You know what? That movie’s hilarious.

Carter: Hilarious.

BTL: I’m glad you highlighted your comedy work in the book, because that’s what made me watch it.

Carter: I know. It’s hard for me to accept that some people really resonate with the comedy or the humor in my work because what I have had done in the past. I have been given honors, and they’d show clips from Malcolm X, and then they went to B.A.P.S, and then they went to Huggy Bear and I’m Gonna Git You Sucka. Then they went to something else, and I was like, “Wait, wait, in between all of that….” They will grab all of the funny stuff, and the serious stuff is left on the floor.

We did show culture of Black history, and Black Panther helped me highlight that part of my career, because people want to see that now, too. At first, it was just the funny stuff, and I was like, “Oh, that hurts me,” because I came into this as a researcher and a person who cared about culture. Now, you’re just acting like it’s a joke, and I shouldn’t have done those funny things.

BTL: Well, for the comedy, a lot of those choices you make are so funny because it’s coming from a researcher and history fan. Deep thought and work went into these very silly, wonderful costumes.

Carter: All right. I like that. I’ll buy that.

BTL: How challenging was it covering 30 years of your career in this book?

Carter: I could have doubled that. That book could actually be three times as thick. I was like, “Damn, it’s thin.” Because we only used 10 or 12 films, but I could tell the story of getting Yellowstone and working with the Westerns and seeing how we all like the same things. Western Cowboys, like hip-hop. I could talk about Seinfeld and doing that pilot and In Living Color.

There were people that were like, “Oh, what about Love & Basketball and Gina and working with women?” I should have had that chapter about working with women in the industry and Gina Prince-Bythewood and Betty Thomas on I Spy. Great people. A lot was missed. I did it while we were shooting Wakanda Forever. Wakanda Forever was four times the size of Black Panther. I was like, “What made me agree to this? “

BTL: [laughs] How did you even find the time?

Carter: It was hard. I was writing a stream of consciousness. I’ve always been a storyteller. If you sit down with me at lunch, I’m going to tell you a story.

BTL: Do you think you’d write a sequel?

Carter: There are two, I think, that I have in me; one is a memoir. I really need to tell people how I grew up because there is a story there — about how you use art to heal. We all have a story, but I think the memoir will actually show you how art is cathartic. Then, I want to do a how-to book. I’m always learning about color theory, and I’d like to take my films and dissect them in terms of color relationships, textures, choices, and vintage versus remakes. I’d really make it a book that a young costume designer could really sink their teeth into, because I follow costume designers on my own.

I followed Ann Roth in her work, and I was mesmerized by how she had such a command with color relationships on film. Places in the Heart and Silkwood have a grit to them, and they had a vintage feel to them that I was like, “I need to be that. I need to be able to do that. How did she do that?” I realized how she could take brown and blue and use it on all layers of it, all tones of it. Just like an artist would add white to a navy and make it sky blue — she could do that. I’d like to make a book that shows people how costume design is an art form because people don’t understand that.

BTL: You also wrote about your shyness around working on contemporary films, which is surprising given you’ve worked on some pivotal modern movies. Where did shyness come from?

Carter: Everybody has an opinion. When you work in contemporary films, especially when you work with an ensemble cast, there’s a lot of dynamics at play. The dynamic of who is the lead, who is the star, who looks the best, that overshadows the characters we are playing. It challenges the actor to actually make a decision about characterization over looking fabulous sometimes. I didn’t want to have that fight. I wasn’t sure about how to deal with the personalities that might come with that. Hollywood supports the personality that’s asking for the Alexander McQueen $2,000 top when I find that this Macy’s top has more character.

BTL: To conclude, what poetry has inspired you lately?

Carter: Ooh. There is one. I’ve been reading about “The Great Migration,” and I’ve been reading “The Warmth of Other Suns” by Isabella Wilkinson. It goes into a lot of firsthand accounts of people who fled the South for the North to get away from Jim Crow and how the emancipation property, how complicated that was, how reconstruction really gave African Americans some hope, and then it was stripped away.

There’s a poem by Ben Chavis, and he was one of the Wilmington Ten, and they were a group of activists in the ’60s. It goes like this, “Chained because of a color which natural to me and forced into a state of tyrannical and inhuman captivity and hearing voices all around me praying for justice to hear my cry, and Lady Justice has deafened her ears. When the pursuit of happiness is only a dream because I can’t even absorb the rays of the sun.” Then it goes on. I don’t remember the rest of it, but it’s a beautiful poem. That poem has been in my mind as I’ve been reading and researching emancipation and migration and reconstruction.

The Art of Ruth E. Carter: Costuming Black History and the Afrofuture, from Do the Right Thing to Black Panther is now available to purchase.