ACE president Kevin Tent opened the annual EditFest Global – a hybrid in-person and online event – taking place on Aug. 27 and 28.

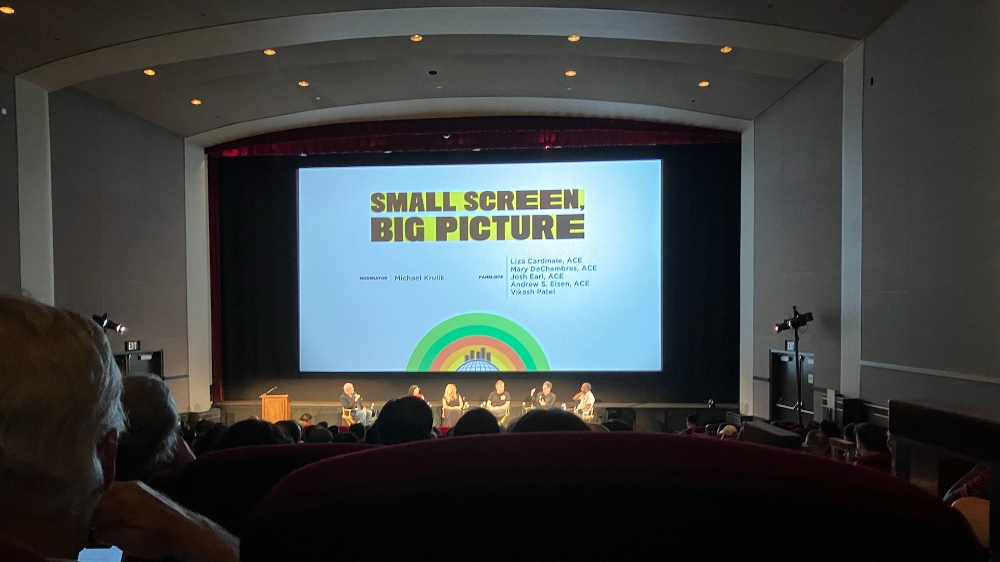

Avid product marketer Michael Krulik moderated the first panel, “Small Screen, Big Picture,” and asked panelists how they started their careers in editing. Liza Cardinale, ACE (What We Do In the Shadows) said she originally planned on being a director, but fell in love with editing while working on a project with editor Carol Littleton, ACE. “I knew these were my people… this is where filmmaking happens,” she said.

Mary DeChambres, ACE (American Ninja Warrior, RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars) started her career as an art teacher and discovered Avid software in her classes. “It was a collaborative learning environment with my students,” she says. “I took to it with such a passion.” After a six-week boot camp at USC and an internship in a music video post house, she got a job at Bunim Murray, where she “learned to edit from their editors.”

When Josh Earl, ACE (Obi-Wan Kenobi) realized that editing “was the filmmaking process,” he scraped together enough money to buy Avid Xpress and then got his start in unscripted reality at Original Productions.

Andrew S. Eisen, ACE (The Mandalorian, The Hateful Eight, Book of Boba Fett) says he was “an artistic daydreamer who watched a lot of movies didn’t realize editing was a career, but eventually found his way there via a first job at a local commercial company.

Vikash Patel (Ozark) also stumbled into being an editor. In university, he wanted to be an animator but taught himself to use Avid Xpress and did an internship at a post facility.

Krulik asked the editors what they love about the genre they work in.

“I love what I love and if I’m having fun, I’ll go after it,” said Earl. “It’s all different muscles but there are things to love about all of it.”

For Eisen, features have been his entire career. “But I admire reality TV editors,” he says. “We start with a script and they are making something from nothing.” More recently, he’s moved into big VFX-driven Marvel movies. When Eisen got a call from Lucasfilm to work on The Book of Boba Fett, a streaming show for Disney Plus, he actually hesitated. “But it was Jon Favreau and I’m a huge fan of his,” he says. “And they wanted a feature editor.”

Patel reveals that he doesn’t like to be pigeon-holed. “I’ve navigated my career to work in all genres,” he says. “And I love a challenge. Although I was with Ozark from the beginning to the end, I don’t typically stay on a program for more than two seasons.”

The editors have a range of feelings about going to the set. Calderone, for one, loves it.

“For a moment, I feel that I’m part of something larger, and how the magic is captured,” says Calderone, whereas DeChambres hates the slow rhythms. “I’d rather look at what I have to look at,” she says.

Eisner says he “always feels like he’s in the way.” For example, on “Season 2 of The Mandalorian, they wanted me on set for [a] fight to make sure they got all the pieces,” he says. “But, generally, I don’t like being on set. It’s unproductive. I like being in my room doing my cut.”

Patel says that “it’s fun going to set and it can be valuable.” “But the director can spend 10 hours on set shooting something I don’t use,” he lamented, “so, I think it’s valuable for editors not to be on set and get attached to footage that took so long to shoot. It’s immensely valuable to be objective.”

In the panel on “Editing Animation: Edit First, Shoot Later,” moderator Bobbie O’Steen, author of Making the Cut at Pixar: The Art of Editing Animation, The Invisible Cut, and Cut to the Chase), noted that “as opposed to live-action, editing is the hub of the wheel for collaboration in animation.”

She asked editor Stephanie Earley (Central Park) what from her past work informed her animation. “I worked on Ghost Hunters for six years, so I came from reality shows,” she says. “I watched all the footage, and it was so much fun. In animation, I had nothing as opposed to too much.” But, she added, “the freedom to create, the chaos and details … make editing animation fun.”

Axel Geddes, ACE (Toy Story 4, Finding Dory) started out acting but fell in love with editing when he sat at his kitchen table and cut Super 8mm films he made. “Out of the blue,” he got a six-week job on Toy Story 2, which led to an opportunity to cut on WALL-E in development. “I learned a paradigm shift in editing animation,” he says. Although storyboarding is typically used to show where the camera goes, in animation, it helps choose the angles that help the audience empathize with the characters. “I use the phrase emotional storyboarding,” he says.

Edie Ichioka, ACE (Toy Story 2, The Boxtrolls, Over the Moon) says her background was documentaries; from there she went into post sound and then the picture department, where she assisted Walter Murch on Godfather III and The English Patient. “This was during the days of film, when the assistant had to be in the room with the editor,” she notes.

Sarah K. Reimers (Finding Dory, Baymax!, Strange World, Piper) started working in the Bay Area on tech sizzle videos. When she moved into stop-motion animation on Phantom Investigators, she realized she had much more flexibility. “We could encourage actors to improv and bring ideas,” she says.

John Venzon, ACE (The Bad Guys, Lego Batman Movie) started off assisting on Fight Club when his friend asked him to help cut a low-budget animation. The friend was Trey Parker and the movie was South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut. “That’s where I learned I had to iterate, iterate, iterate,” he says. “The key thing I learned from Trey and Matt [Stone] was whether it was the idea that was bad or the execution.” “Animation is my favorite genre of editing,” he adds. “You’re in the writers’ room for the entire time.”

The editors gave shout-outs to their valuable assistant editors. “Assistant editors are key,” says Ichioka. “Their level of organization involves such minutiae. We’re constructing audio performances out of things that are repurposed because AEs can keep it organized and findable.”

Day 2 of EditFest Global began with a keynote by Eddie Hamilton, ACE (Top Gun: Maverick, X-Men: First Class, Mission: Impossible – Fallout, Kingsman: The Secret Service), in conversation with Hollywood Reporter tech editor Carolyn Giardina. Hamilton revealed that his interest in filmmaking was sparked by seeing Star Wars as a child. Throughout university, he edited student films and, after graduation, found a job as a runner in a small post-production facility. There, he learned Avid Media Composer and became editor of a low-budget indie film — 1998’s Urban Ghost Story.

After meeting Producer Matthew Vaughn while editing Mean Machine, Hamilton got his first big break on Vaughn’s 2010 comic book movie Kick-Ass. “After that, he took me to X-Men: First Class, where I had the honor to work with an idol of mine, Lee Smith, ACE, who had just done Inception and The Dark Knight.”

Hamilton admitted that one of his “bad habits as a young editor” was to try to use all the coverage. “Now, many years later, I know that you’re trying to dial in the emotion of the scene immediately,” he says. “If the shot isn’t strong, don’t use it. You need committed storytelling for every shot.”

He also observed Smith politely telling studio heads that they couldn’t watch certain sequences that the director had not yet seen. Additionally, Hamilton noted the importance, especially on big movies, of turning over VFX shots very quickly.

“Understanding VFX workflows is something which, the further up the movie ladder you get, the more important it is [that] you understand the priorities.”

The last panel, “Editing for the World,” moderated by Alexander Berner, ACE (Babylon Berlin, Resident Evil, Cloud Atlas), brought together a group of editors from around the world. Spanish editor Jean-Daniel Fernández Qundez, ACE (The Witcher, Lupin) noted how, for 50 years, “most of the shows we saw came from the U.S.” “The language of U.S. cinema influenced us and we’ve been trying to emulate it,” he says. “The audience has also been used to this kind of language. They ask for what they like, but I don’t think we should always give them what they think they like. Maybe we can subvert that.”

Danish editor Kasper Leick (A Royal Affair, Borgen) agrees, saying that “there is a formula that is being reproduced — still, surprisingly few TV shows really stick out.” He reveals that, even after the Danish show Borgen found enormous international audiences, the writers continued writing for Danes. “Denmark is [a] place where you still take chances,” he says. “Although the show is very American, it’s not a problem in the writing room.”

South African editor Melissa Parry, SAGE (South African Guild of Editors) believes that “maybe we fall into a trap of replicating some things because we need to keep people beyond the first 10 minutes,” noting that “there’s a loss of patience in TV, unlike film.

“Every kind of art needs a new flavor,” added Egyptian editor Ahmed Hafez (Moon Knight, Paranormal).

Moderator Berner then asked about the impact of subtitles on their projects, opining that, “subtitles [are] becoming part of the creative process of editing.”

Qundez said that subtitles don’t bother him. “I come from a culture in Paris where everything we watch is in English or German or Danish with subtitles,” he says. “These subtitles give me some coherence, but I don’t think they’re part of the process.”

Parry points out that South Africa has 11 official languages, so many shows are not in English. “I find it quite liberating,” she says. “I’m using the actor’s body language [and] voice intonation to guide how I’m cutting, more than dialogue. I don’t see it as a hindrance.”

The editors didn’t feel as sanguine about dubbing, however.

“In Germany, you’re used to watching dubbed movies, but it’s not an experience I like,” said Leick. “In Denmark, we watch with subtitles.”

All the editors recounted positive experiences of collaborating with other editors, sometimes across countries.

“I found it very important and useful to share what we’re doing and take opinions,” says Hafez, who worked with Joan Sobel, ACE on Moon Knight.

Qundez said that on The Witcher, he was working “with editors all over the world.” “Even with different cultures and backgrounds, we all reacted exactly the same to the cuts and characters,” he said, while Leick recounted the experience of supervising three editors on a documentary series.

“I really enjoyed that as a different kind of editing — supervising other editors and looking at the overall structure, music, graphics and letting the actual editing be the work of others. That was very successful,” boasted Leick.

Finally, Berner asked the editors to recount the pros and cons of working with the big streaming companies. Leick reports that the streamers have created an “enormous production boom” in Denmark, which is only now beginning to settle down.

“A lot of interesting series have been made and it’s allowed a lot of people to get in the business and get working,” he says.

Parry actually gave the big streamers credit for devoting more time to the editing process. Qundez agreed, pointing out that, the streamers have upended a three-tiered curse:

“No cinema actor would do a TV series in France, but with streamers, well-known actors are starting to come to the series. Also, thanks to the streamers, many production companies realize that [extra] time [means added] quality in writing, shooting, and mostly, editing,” he says. “We editors started getting double the time and production companies realized editing time had a direct relationship with the quality of the program. We are now finding ourselves proud to show the world that we could do successful series, and that has given us a huge amount of positivity in our industry.”