Sir Kenneth Branagh returns as detective Hercule Poirot in Death on the Nile, which is based on one of Agatha Christie‘s edgier mysteries. The whodunit-at-sea also stars Gal Gadot, Emma Mackey, Annette Bening, Armie Hammer, and Russell Brand, so there are plenty of suspects to choose from.

Set among Britain’s ultra-rich, the film unfolds in Depression-era posh resorts, magnificent Egyptian ruins, and, for long stretches, aboard the Karnak, a luxury yacht. For production designer Jim Clay, “Our whole aim on this was to take the audience on a glamorous, opulent, elegant journey along the Nile, during which all these rather darker things happen.”

Clay collaborated with Branagh on his previous Christie adaptation, Murder on the Orient Express, as well as the coming-of-age drama Belfast. When he spoke via Zoom with Below the Line, Clay singled out the contributions of Director of Photography Haris Zambarloukos and Visual Effects Supervisor George Murphy.

“I design the sets mostly as a composite world,” Clay explains. “Ken’s very good at reading plans, and Haris is always at those preproduction meetings, so we are planning together. Then George can take my designs and plans and pre-vis them into a digital model with characters moving around.”

Michael Green‘s screenplay for Death on the Nile follows a honeymoon party traveling by yacht from Aswan to the temple of Abu Simbel, with its towering sculptures of Ramses the Great. Everyone aboard the yacht becomes a suspect when a passenger is found murdered.

Clay points out that the film relied heavily on visual effects, explaining that “The river water, all the banks of the Nile, much of the Hotel Cataract exterior were visual effects. It was a close collaboration with Haris and George about how that would all work so it would look seamless.”

Branagh wanted the freedom to shoot incidents in the story from a variety of intimate angles. Weather proved too unpredictable to work on real locations, so Clay had to provide the equivalent of fully functioning sets built on soundstages in England.

“The Abu Simbel temple set was almost full size, perhaps 90 percent,” Clay says. “It was a big build because I think it constituted only four or five days of shooting. It was about 80-feet high and about 100-feet wide. It was sculpted exactly as the original, except that it was styrene and plaster rather than stone.”

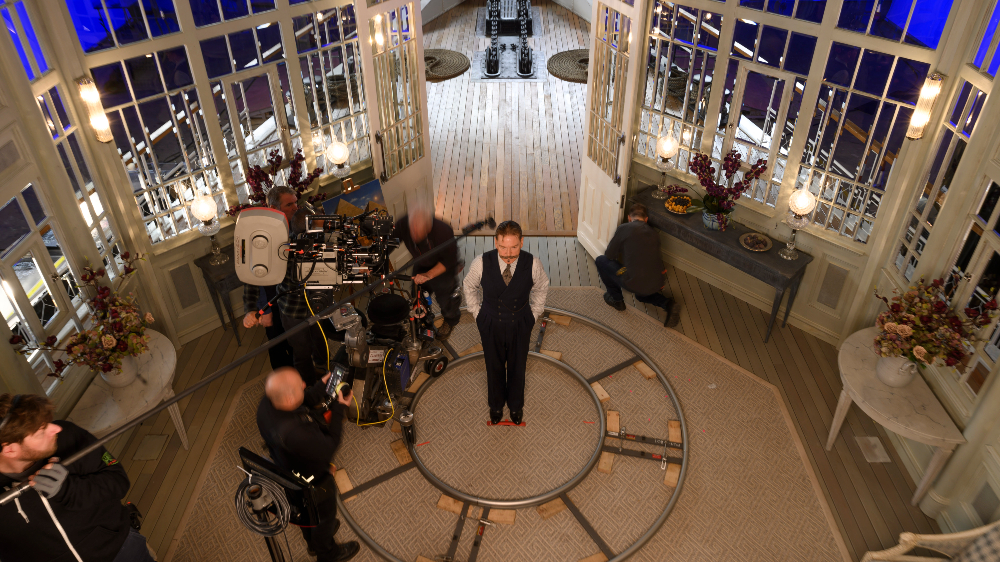

“We built the entrance to the interior and placed gantries above the set so we could have cameras looking down on the performers,” he adds. “We had an expanse of sand in front of the set so that we could digitally place the Nile.”

The Karnak was an even more impressive build. Again, the original plan to shoot a real ship on a lake in Morocco turned out to be too complicated.

“Instead, we ultimately decided to build back in the UK. We used a double rail track so we could slide rather than float the boat in and out of a stage,” Clay explains. “We placed all the water in digitally with the exception of a one-meter-deep tank along one side of the boat. That way we could have the reflection of water on the hull of the Karnak.”

The yacht is distinguished by Clay’s extraordinary use of glass panels and doors, a holdover in some ways from Murder on the Orient Express.

“When we did Orient Express I used glass panels between the carriages, panels with beveled glass,” Clay says. “Haris took great advantage of that. So for Death on the Nile, we wanted to repeat that psychological climate.”

Clay’s design allows the camera to sweep through rooms of the yacht, but also to pause and capture the characters reflected and distorted in ways that mirror their emotions.

Death on the Nile takes place on a larger scale than Murder on the Orient Express. It starts in the trenches of World War I, where Poirot uses his deductive skills to time an attack on the enemy. The scene unfolds with prolonged Steadicam shots that evoke Stanley Kubrick‘s Paths of Glory.

“That was shot on the backlot at Longcross Studios in Surrey,” Clay says. “Ken is a director who likes to have control over his working environment. So building is often the best option for him. We dug the trenches, collaborating with Haris so we knew where the cameras needed to go.”

Not all of the sets in Death on the Nile were as elaborate. The nightclub where Poirot watches a blues singer played by Sophie Okonedo, for example.

“Construction on that set was actually quite minimal,” Clay says. “It was a big black void into which we built certain elements. In particular, some of the painted backgrounds you’d find in jazz clubs of the era. It was down to Harris really. He lit the areas he wanted in pools of light. So I think that set probably felt rather bigger than it really was.”

The sumptuous sets in Death on the Nile help capture the glamour of life among the elite during the Depression. Clay freely admits that he stretched some of the film’s period details.

“I think we try to be embedded in the period, but we do like to take liberties a little bit,” he says. “We try to accommodate the camera, the shots we want to take and the atmosphere we want to create. We also wanted to reach out to a contemporary audience.”

Pointing to the work of costume designer Paco Delgado, Clay adds, “His costumes were of the period, but in a style that you could step out into the street in them today and they would just be considered elegant and stylish rather than unusual. So we were all trying to span the contemporary world with the period world in a way to make it appealing and accessible to a young audience.”

Death on the Nile is currently playing in theaters nationwide.