Anyone who has ever weathered bleeding fingers deciphering the threading diagram of a Moviola can tell you the day they saw their first video playback system on set.

Along with anamorphic lenses, the Steadicam, computer-generated Imagery, camera drones, and wireless LED lighting, innovations such as that one have been game-changers in the process of making television programs and motion pictures. Their impact, along with a slew of other technological breakthroughs, has fundamentally transformed the process of filmmaking in recent years. But among that list, there is only one invention that has altered the people behind it:

The cellphone.

Film and television production crews are an anomaly in the business world. An exotically composed soup on a menu filled with chicken broth. It is rare to find a collection of employees working toward a common goal who are truly gifted with such a wide range of talents and genuine affinity for their respective crafts.

Motion pictures bring together skills that in most corporate applications would never intersect. Architecture and design meet sewing. Transportation meets lighting. Mechanical logistics meet acting. Electricity meets art. This proximity is why movie sets are brimming with some of the most interesting people in the world, many of them coming to their careers from oblique paths. While a great majority of occupations have employees with similar experiences and training, every person on a film set has forged a unique capability and work history. This amalgam of artists creates a group of driven, idiosyncratic people who are thrust together for extended periods of time.

Enter the cellphone.

In the early ’90s when I was driving a rumbling five-ton truck around Los Angeles the pager was king. When that annoying box on your belt started vibrating and flashing a phone number with a “911” next to it, it was time to start scanning the landscape for a pay phone and a place to pull over safely and quickly. Pay phones were unreliable and carried the scent of the last 50 people who used them, so wading through the olfactory assault was nothing less than Herculean.

But mobile phones changed all that.

The seismic shift in communication and the subsequent social media onslaught did not happen overnight. Mobile phones were closer to a tool, like a hammer or a drill. Something that was part of your kit. Their expense made them a luxury, so their use was judicious. At the end of the job, the telecommunications bill had to be poured through and the business calls added up by the minute for production reimbursement. On set, they were used only in emergencies. Making a phone call usually meant a hunt for a stage phone with an outside line, a nearby pay phone, or a local business you could intrude upon for a favor. That situation seems ridiculous now, but a phone call required a plan. So, what did people do in the downtime between takes when there was no phone full of games, social media, news, side hustles, hookups, and text conversations to pass the time?

We used to talk.

While a feature may take months to complete, a television series several weeks, and a commercial several days, the dynamics of crew relations are roughly the same. The individual departments grow on their own until the actual shooting starts, and then a “company” is formed. For me, this was always the most fascinating part of the job — passing time by bonding over the work and creating friendships, whether short-lived or long-lasting.

I came up through the business as an Art Department Leadman in commercials, and that was always my crew experience. After my focus shifted to Decorator, I spent a lot of years working on Variety and Reality Shows and hadn’t been on a traditional shooting set since before cellphones jammed with social media platforms and streaming video became ubiquitous. On my return to commercials in 2012, I remember everyone working together to get the first shot, like always, and I watched the cameras roll on the first take.

The director said, “Action,” and something completely foreign to me happened. Every crew member not involved with the scene dove into their phones. In the past, this is when non-essential crew would step back from the set and relate to each other as people. Just off set, there would be a low murmur of crew members sharing stories and talking about other jobs or their families. The usual interpersonal chats that lead to familiarity.

This set was dead silent in every corner.

Unless there was an immediate work-related question, I felt that approaching someone would have been perceived as a rude interruption to whatever was happening on the black rectangle lighting their assembled genuflected heads. Although the assistant directors enjoyed not having to constantly remind the crew to quiet down, the scene struck me with a sense of loss. A loss that reminded me of a PSA produced by Kodak years prior that defended film against the inevitable takeover of video. In it, the late, great Director of Photography Jordan Cronenweth pointed out the limited amount of light stops that video could perceive and capture as opposed to the infinite number of stops captured by exposing film.

Before I hear, “Okay, Boomer,” or “Find a rocking chair, grandpa,” I have a few simple questions: Have we lost the subtlety and nuance of connection? Has the cellphone burned through all the delicate light stops in communication and isolated us in the very environment that used to bring us together?

From 1993 to 2003, I had the good fortune to be part of the production team that created scores of Jack in the Box commercials, three to four times a year. These spots were extremely popular, sold copious amounts of hamburgers, and won every advertising award on the planet. Besides making me enough money to buy a home, which I sometimes refer to as the “House That Jack Built,” I got to spend time with some of the most fascinating and talented crew people in Los Angeles.

As a set decoration buyer, pre-production was quite different without the cellphone and its ability to send pictures instantaneously to shared websites and live documents. I developed film and organized the prints into a shoe box, drove out to the production company’s office, and met with the Set Decorator, Production Designer, Director, and Producer. All of us would pour through the photographs and select our hero looks. Every department had a similar experience. That contact created a bond with the final product that no longer trickles down to the crew these days, based on my recent experiences.

On the Jack sets, the crew would mix between setups. Besides meeting new people, there was a coming together to catch up as people and colleagues. A first-hand account. Not filtered through the lens of Facebook and Instagram. There was also the human experience of sharing our struggles, triumphs, and, of course, a few laughs, about what was going on, both in our lives and careers.

Today, crews don’t seem to have the same interest in the process itself, rather, only their part in it. It is an almost imperceptible difference, but one that has led to a gradual change. I’ve watched people stalk a stranger’s social media from their name on the call sheet to get a sense of who they are, rather than just walk up and start a conversation. And most times, their journey of discovery would stop right there, especially if their target had a significant other. A particularly sad comment that relates to the furthering of singular intentions.

Set protocols have become more efficient, with answers and information coming at lightspeed thanks to the cellphone, but the eventual death of interdepartmental relationships has crept through production crews like a hand slowly squeezing its way to a full strangle. Naturally, Covid made this worse, exacerbating the problem with the rise of Zoom meetings, but even before the pandemic, a lack of direct interaction had sent us all into private work isolation booths.

A seasoned decorator once said to me about the business, ‘The one thing you can count on is change.’

I’ve always lived by that phrase in my career. Every job comes to an end, every business relationship can go south (and hopefully, north) at any given time. And the cellphone has ultimately become invaluable to the process of filmmaking. Like the Steadicam, drones, and every other technological innovation over the past 30 years, its value cannot be overstated. But with every gain, there is an equal and opposite loss.

Watching the deterioration of human connection on set led me to change the way I deal with my own crew. As a key in this stage of my career, I try to make sure my crew feels supported, and perhaps most importantly, like a team. That’s what it means to create a bond on set. I’m a storyteller to a fault and have bored the hell out of many set dressers with rambling production yarns and slinging barely cogent bon mots. My aim, however, is that my example will move them to engage more with the process as well as the people involved in it.

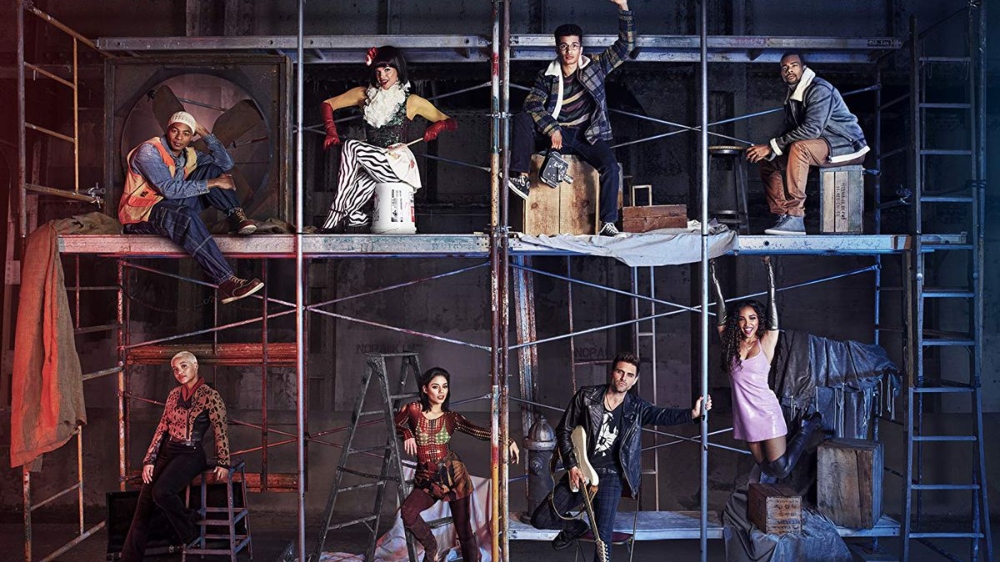

In 2019, I saw my wish for a return to more personal connection on set granted while working on Fox’s presentation of Rent: Live. It was the first time in years that I witnessed crew members in every department fully invested in a project and the people who were making it. Maybe it was the phenomena of live theater, or maybe the gravity of the subject matter, but something clicked on that production.

The glow on everyone’s face was not from the clean LED of a cellphone. It was from genuine emotion. We may have lost some sense of connection in recent years, but hopefully, in keeping with this business, we can reboot that and get back to the good old days. So the next time you see me on my phone on set, don’t be shy… be the change and come say “hello.”