In the 128-year existence of motion pictures, makeup artists have been critical to the successes of all types of films in every key period of time, from the earliest silents, to the classic Golden Age of Hollywood, and into the modern world of freelance artistry. All of the major film studios boasted its own makeup department, and, with that, a makeup department head, most notably from the mid-1920s to the mid-1960s. Including all of the mainstream production entities, no individual is more significant to a studio’s work than makeup artist Jack Pierce, the legendary monster-maker who worked in the 1930s and 1940s at Universal Pictures during their classic horror cycle. From 1928, when he was designated makeup department head, until his unceremonious dismissal in 1947, Pierce created some of cinema history’s most distinguishable screen characters.

After immigrating to the United States from Greece at the turn of the 20th century, Pierce moved to Chicago then California, attempting many different careers before his journey into show business. He tried to play professional baseball before working in the fledgling motion picture industry for Harry Culver, founder of Culver City. Pierce managed movie theaters in the 1910s then worked as a stuntman and actor at both Universal and Vitagraph from 1916 to 1924.

Simultaneously, Universal was a growing studio in the San Fernando Valley, dubbed “Universal City” in 1915, after only three years in business. Evolving out of a distribution business created by German immigrant Carl Laemmle, Universal was an active production hub its first ten years in operation. Like many at the time, Pierce was a struggling actor, but he had an edge in that he learned to create his own unique makeups on himself, transforming his entire face and body in the process. It is unlikely that Jack Pierce knew then that he was preparing for a career which would become unprecedented in motion pictures just a decade onward.

After going to Fox Film Studio to create a successful simian makeup on actor Jacques Lerner for The Monkey Talks in 1927, Universal soon made Jack Pierce the studio’s first official makeup department head. Since the studio had reaped massive box office returns on the Lon Chaney films The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925), new production chief Carl Laemmle, Jr., Carl’s only son, decided to thereafter produce serious screen versions of several classic horror novels. In 1928, The Man Who Laughs was one of Pierce’s early challenges as he devised the makeup for Conrad Veidt playing the tragic lead character of Gwynplaine. Many have cited that makeup being the key inspiration for the look of The Joker character from the Batmancomics.

Without question, “Junior Laemmle,” was Pierce’s trusted confidant at Universal in the early 1930s; moreover, Junior Laemmle’s personal tastes were profoundly fortuitous for Pierce’s assignments at the studio during that decade. In 1930, the horror classic Dracula was first produced, and though star Béla Lugosi refused to let Pierce apply his Count Dracula makeup—the Hungarian actor had always created his own makeup on stage—Pierce conceived the visual appearance of the historic vampire. Though no screen credit was given for Dracula’s makeup, Pierce’s personal touch remains intact on that film.

Naturally, after the success of Dracula’s release in February of 1931, Junior Laemmle wanted a follow-up, which led to the production of Frankenstein in summer of 1931. Though historians have argued as to whether director James Whale, actor Boris Karloff, or Junior himself contributed to The Frankenstein Monster’s iconic makeup, the driving force behind the look of the character incontrovertibly belonged to Jack Pierce. Each morning, Karloff sat in Pierce’s chair in his Universal makeup bungalow for four hours, enduring the cotton-collodion-spirit gum concoction on his head and face as Pierce and his assistants applied the makeup that would make him into the movies’ most memorable monster. For 43-year-old Karloff and 42-year-old Pierce, The Frankenstein Monster was an achievement that would have cemented their legend after that one film. Alas, they were only beginning their wholly unique actor-makeup artist partnership.

In 1932, Pierce and Karloff teamed again to create two films: The Old Dark House and The Mummy. Another Whale film, The Old Dark House, a classic haunted house film, features Karloff as demonic butler Morgan in another memorable genre incarnation. For their next film, The Mummy, Pierce created several makeups, the crowning achievement of which is Pierce’s full top-to-bottom makeup on Karloff as Im-Ho-Tep. Though the actual creature is only seen on film for a few seconds, when Im-Ho-Tep comes alive and parades across an unearthed Egyptian tomb, the moment was another landmark in cinema horror.

In interviews, Pierce claimed that the entire Im-Ho-Tep makeup required eight hours to produce, including burning the bandages that Karloff wore and adding Fuller’s Earth that would fall off of the character as he came to life. Karloff spent the remainder of the picture as Ardath Bey, another Pierce character as a heavily wrinkled Egyptian prince looking for his lost love.

With the early 1930s providing countless successes, the Laemmles attempted to produced sound versions of both Phantom and Hunchback, but neither materialized. At this time, the studio also developed a version of The Wolf Man with Boris Karloff, but this, too, would be derailed due to production problems. In their place, Universal decided to produce a sequel to an already successful horror film, starting a trend that would result in numerous Dracula, Frankenstein, and Mummy spin-offs which became their trademark, especially in the 1940s.

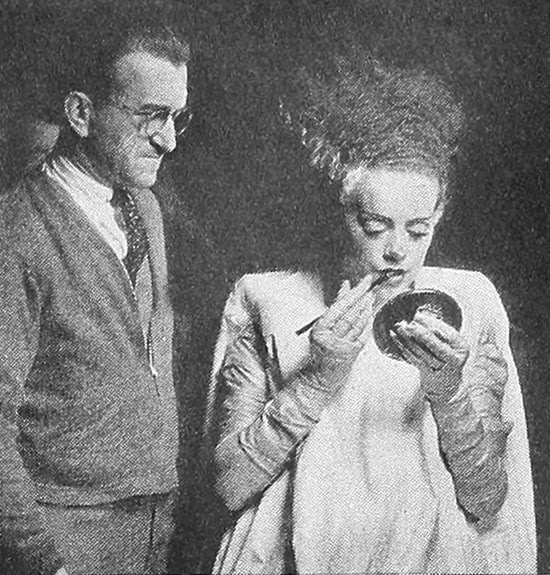

The first true horror sequel in Universal’s canon was The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) for which Pierce revamped his first version of The Frankenstein Monster by adding a burned forehead and clamps for the top of Karloff’s head. Pierce also created the famous makeup and electric hairstyle for Elsa Lanchester’s titular bride character, who appears, unforgettably, at the very end of the film.

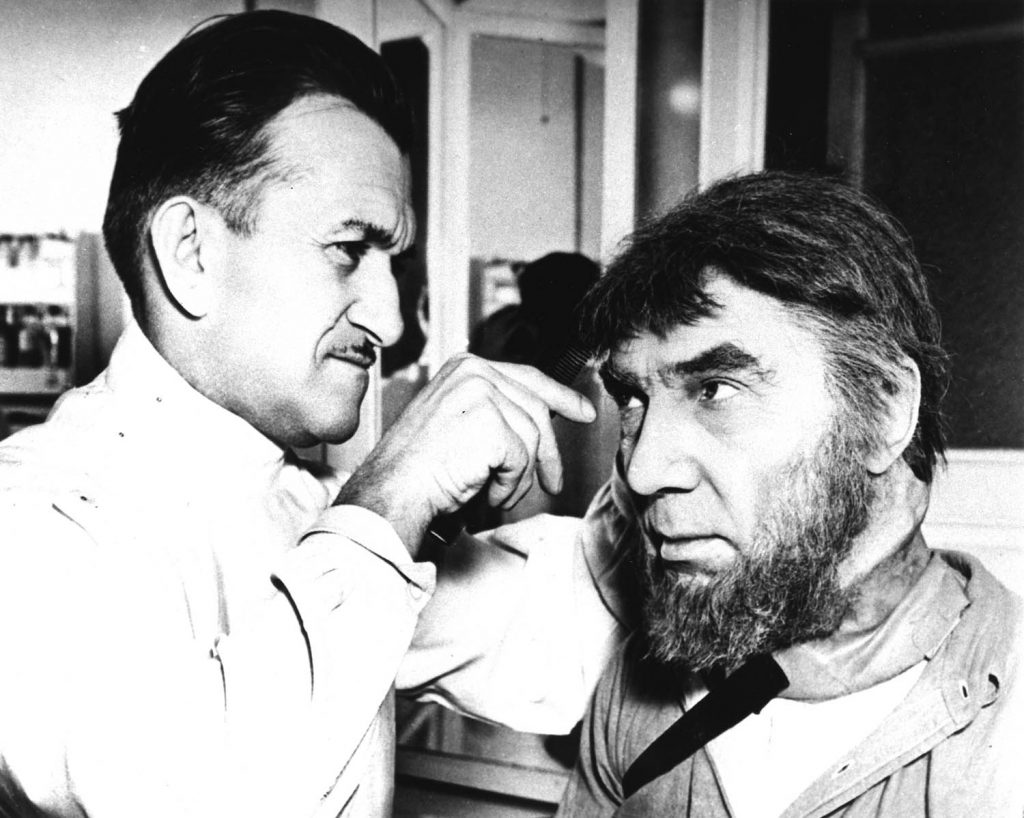

After the troubled Laemmles sold Universal Pictures in 1937, a series of revolving studio heads at Universal called upon Pierce for the last 10 years of his Universal career. For Son of Frankenstein (1939), Pierce was summoned to again work with Béla Lugosi. Despite their awkward introduction earlier in the decade on Dracula, Pierce created Lugosi’s second most memorable makeup character with the Ygor character he played in both Son of Frankenstein and later Ghost of Frankenstein (1942). The bearded, gnarled-toothed wretch, Ygor became Lugosi’s most notable character in many years, while Karloff’s makeup as The Frankenstein Monster was revised yet again for a fuller facial look in the actor’s final turn as the character.

Two years after Son of Frankenstein, Pierce was again able to deliver an original monster character, with Lon Chaney, Jr. in the title role. Though the two did not reportedly get along — Chaney did not like wearing the uncomfortable makeup or undergoing the lengthy application and removal period — Pierce excelled once more with his werewolf concept, utilizing a design he had created for Karloff a decade earlier. Unlike the toned-down Werewolf of London lead makeup from 1935, with The Wolf Man, Pierce designed a character on par with his original Frankenstein Monster and Im-Ho-Tep monsters. The Wolf Man, always starring Chaney, Jr., would make several more screen appearances in the 1940s.

Amid a rash of sequels and one-off pictures, the final, original Universal makeup realized by Jack Pierce arrived in 1943 with a revised Phantom of the Opera movie. Starring Claude Rains, it would be the only Jack Pierce movie photographed in color until the 1960s. Though his treatment of Rains’ scarred makeup—revealed only at the end of the film—was cut down at the behest of the producers, the makeup on Rains stands as another horror movie landmark.

In the early-to-mid-1940s, most Pierce makeups were reappearances of earlier characters; mummies, vampires, Frankenstein Monsters, and wolf men were conjured for various Universal sequels that ran from 1940-1945. Pierce also created a female beast for the Jungle Captive/Captive Wild Woman films. Arguably, the overall quality of the films and makeups in this era was generally not on par with the work in the films of the 1930s.

After World War II, Jack Pierce’s reign at Universal Pictures ended when the studio merged with International Pictures and replaced many of its longtime artists. Though he had been a makeup department head at the studio for 19 years and worked at the studio for over 30 years, Pierce ended his career working elsewhere on low-budget films and television during the final 20 years of his life. Some of his later films included Creation of the Humanoids in 1962 and Beauty and the Beast in 1963. His last project was working as makeup department head for the TV show Mr. Ed from where one of his final challenges was aging star Alan Young to play his own father.

Following Mr. Ed, Pierce retired in 1964 at the age of 75. Unconscionably, Pierce died in obscurity in 1968, likely thinking that he had been totally forgotten. However, thanks to Famous Monsters of Filmland Magazine and nationwide TV horror hosts, Pierce’s work was presented to new generations of fans in the 1960s and 1970s. As a result, it is agreed upon by many top modern artists that Jack Pierce is undoubtedly the father of the monster makeup and its foremost driving force in cinema during the birth of the horror genre.