Traveling to Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in February 2012, director Orlando von Einseidel planned a feel-good documentary about park rangers protecting Virunga National Park, the home of the last remaining mountain gorillas. Instead, when renewed civil war is fueled by corporate lust for oil, von Einseidel became a courageous witness to a desperate fight for the soul of the Congo.

“I went out to tell a positive story about the rangers of the park rebuilding their country after 20 years of war, because the park is really driving forward development in the whole region. That was the story I went to tell, this transformative story,” shared von Einseidel. “When I got there, I learned almost immediately about this oil company, SOCO International, and what they were doing. Within a couple of weeks, a new war started, so the story took this huge U-turn very quickly.”

Although the film is a non-fiction chronicle of unfolding events, the documentary combines the drama of international intrigue with an action-packed war story and the tension of an on-the-edge-of-your-seat thriller. The investigative reporting in the film uncovered the destabilizing practices of a transnational corporation that sought to exploit the natural resources in the DRC, even if profits were achieved by displacing, torturing and killing the indigenous peoples whose lands they coveted.

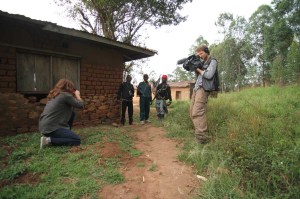

“I learned very quickly that the park had these very serious concerns about SOCO International. They had started an investigation themselves, along with fishermen living around the lake and civil society groups. They had been doing it on their own, very isolated. They were receiving death threats. No one knew about any of this and it was very dangerous,” Von Einseidel continued. “I realized I could contribute technology.”

The director’s background included journalistic investigative reporting. Having worked with undercover cameras on other films, he trained people to use that equipment. Then they were able to gather concrete evidence, which he collected and triple-backed up on drives that were encrypted for security.

The director’s background included journalistic investigative reporting. Having worked with undercover cameras on other films, he trained people to use that equipment. Then they were able to gather concrete evidence, which he collected and triple-backed up on drives that were encrypted for security.

All their emails were also encrypted because anyone who expressed opposition to the oil exploration received death threats, or was arrested, tortured, beaten up and, as some journalists believed, even murdered. The filmmakers kept themselves under the radar to avoid any problems.

“We had to be incredibly careful. A lot of people risked their lives to gather up evidence against SOCO International. It was very, very dangerous work,” shared von Einseidel. “Some very powerful people never wanted this film to see the light of day.”

About six months into the investigation, von Einseidel met freelance journalist Melanie Gouby. “She knew some of the guys working for the oil company. I thought it was worth the risk to tell her about what we’d been doing,” revealed von Einseidel. Gouby agreed to work with him. After learning how to use the undercover cameras, she “started to run with this herself and very quickly was bringing back this incredible material.”

About six months into the investigation, von Einseidel met freelance journalist Melanie Gouby. “She knew some of the guys working for the oil company. I thought it was worth the risk to tell her about what we’d been doing,” revealed von Einseidel. Gouby agreed to work with him. After learning how to use the undercover cameras, she “started to run with this herself and very quickly was bringing back this incredible material.”

Because button cameras are difficult to focus, in one scene they ended up getting a shot of the tablecloth, so cutaways were filmed later, but other than a few shots like that, all the footage was real.

For the first year, and as is common with many documentary filmmakers with no money, von Einseidel worked on his own in the park, living with the rangers in a tent, shooting, capturing sound and backing up footage. “Most of the film was vérité sequences filmed by me with a small camera,” said von Einseidel, who worked with a Canon 7D for the first year and a half.

Towards the end of the project, cinematographer Franklin Dow was brought out to shoot aerial, landscape and wildlife footage using a Sony F5. The production was shot using a variety of different cameras including the Canon C300, an aerial camera and the button cameras. The director had previously worked with Dow on a number of films.

Towards the end of the project, cinematographer Franklin Dow was brought out to shoot aerial, landscape and wildlife footage using a Sony F5. The production was shot using a variety of different cameras including the Canon C300, an aerial camera and the button cameras. The director had previously worked with Dow on a number of films.

Editing started about a year in. “We were almost filming three separate films. We were very aware that we were filming this undercover, investigative film, like a PBS Frontline-type film. We were almost filming a nature documentary with all these incredible animals and landscapes. And then we were filming a war movie,” explained von Einseidel. “It was complicated to pull all these different elements together to create something coherent, but we always knew that the power of this film was combining these cinematic compositions into a single story – combining all these different character stories and bringing it all into one film.”

The soldier turned park ranger, the park director of royal blood, the caretaker of the gorillas, the young, female journalist and the park itself were central characters in the film, whittled down from about eight characters followed during the course of the shoot, which produced about 300 hours of footage.

The soldier turned park ranger, the park director of royal blood, the caretaker of the gorillas, the young, female journalist and the park itself were central characters in the film, whittled down from about eight characters followed during the course of the shoot, which produced about 300 hours of footage.

Several editors worked on the project. The first two editors, Peta Ridley and David Charap helped build sequences, contributing to the rough cut, but according to von Einseidel, “It wasn’t the film that our ambitions wanted it to be.” Narrative editor Masahiro Hirakubo, who edited a number of Danny Boyle’s early films, came on board and “really carved the narrative with us and built the film that it is today.”

The director continued, “We felt that a narrative editor was the right choice for this film because it played out in real life more like a narrative than a normal documentary. Also we knew that we wanted to make this film exciting so as wide an audience as possible would learn what was happening in this park. It felt right to go with a drama editor.”

When Hirakubo had to move onto another film, Katie Bryer and then Miikka Leskinen joined to finesse and finish the film for the Tribeca Film Festival premiere in New York City on April 17, 2014 and the Nov. 7, 2014 Netflix release respectively.

When Hirakubo had to move onto another film, Katie Bryer and then Miikka Leskinen joined to finesse and finish the film for the Tribeca Film Festival premiere in New York City on April 17, 2014 and the Nov. 7, 2014 Netflix release respectively.

Von Einseidel has collaborated with composer Patrick Jonsson for a long time, on many films. The composer was told of the project a year before he actually started working and fully understood what the director was trying to do with the film.

“I think he’s a brilliant composer. He is very sensitive. He immersed himself in the sounds of Congo, the history, the politics. He wanted to create a score that was steeped in Congolese feeling, but also had the dramatic elements we needed for a movie. I think the end result is musical,” said von Einseidel. “He used a lot of local instruments. There is nothing in there that sounds obviously Congolese, but there are a lot of Congolese sounds within the score. In the layers you start to pick up things that you wouldn’t hear if it was just a classical, Western orchestral sound.”

A variety of sound devices were used during production. Sound environments varied from interviews to racing in a car through the war zone. The director worried how the audio would come together and feel like a single film.

A variety of sound devices were used during production. Sound environments varied from interviews to racing in a car through the war zone. The director worried how the audio would come together and feel like a single film.

“There was a lot of running around in this film. Doing the sound, and the shooting, and everything on my own, was definitely hard to keep it all at a top level of quality, but we worked with a fantastic team at a postproduction house called Molinare in London,” remarked von Einseidel.

Sound editors Claire Ellis and Tom Foster were respectively tasked with dialogue and effects editing. Re-recording mixers George Foulgham and Nas Parkash “were brilliant, and did an incredible job of cleaning up all the sound I brought to them and making it sound dramatic – the subtle additions and the textures. I’ve never worked with people as talented as them.”

Although von Einseidel admits the list of crew that he would like to credit for their contributions is endless, he wanted to give a shout out to his assistant producer Patrick Vernon – who risked his life for over a year on the ground in the DRC with the director – and his producer Joanna Natasegara who came on board a year into project and “really turbo-charged it from a producing point of view.”

Natasegara’s role was always “to take the film and make it have real social impact on the ground.” Von Einseidel elaborated, “To actually use the film to drive forward change, in our case, to protect the park from this oil company. She’s done an amazing job.”

Natasegara’s role was always “to take the film and make it have real social impact on the ground.” Von Einseidel elaborated, “To actually use the film to drive forward change, in our case, to protect the park from this oil company. She’s done an amazing job.”

Before the release of the documentary, the filmmakers informed SOCO of the allegations within the film, asking for their response. SOCO’s lawyer responded with a 20-page legal letter denying everything. The company also threatened to sue the filmmakers if the film was released, festivals that might screen the film and journalists who posted reviews of the film.

“They were very, very aggressive. That’s very scary,” said von Einseidel. “And on the ground the situation is still very much the same.”

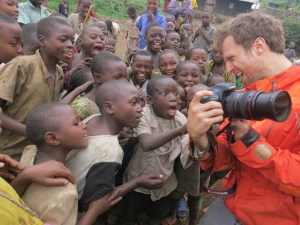

Nevertheless, the director is optimistic about the outcome of the conflict because of the integrity and courage of the people involved in fighting for the park, like warden Rodrigue Katembo and gorilla caretaker Andre Bauma. “The rangers, I’ve never met people as brave. They wake up every day and risk their lives because they believe in something bigger. It’s humbling. They represent the best of humans. With them at the forefront of this fight, I think they will win.”

With its BAFTA and Oscar nominations, the film has come into the media spotlight, which has exerted pressure on SOCO by bringing the park’s problems to international attention.

“People recognize that what is happening to the park is a metaphor for the wider conservation battle happening across the world,” commented von Einseidel. “They recognize that if somewhere as iconic as Africa’s oldest national park and home to the last mountain gorillas, if somewhere that important – a World Heritage Site – is destroyed for corporate interests, what can be protected on our planet?”