When Charlie Chaplin famously roller-skated on the brink of a large department store drop-off in Modern Times in 1936, few in the audience realized that Chaplin was in no danger of falling many storeys below. A painting on glass of the drop-off was carefully placed on the set and lined up for the movie camera so as to create the final illusion of open space below where none actually existed. In the many decades since, filmmakers have attempted to enhance such magical illusions with every technique possible, always striving for greater panoramas and verisimilitude.

Recently, some of the top craftspeople working in the visual effects field met at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Linwood Dunn Theater to discuss the emerging digital technologies and their effect on filmmaking. Specifically, the group discussed digital’s ability to extend sets beyond the basic three-wall concept that existed in Hollywood for a century. Now, with a variety of tools and skilled artisans at effects houses, filmmakers are able to build limited sets, which must exist for the placement and movement of actors in the physical world, while still enjoying the freedom to expand those sets to seemingly endless boundaries in the digital world.

One leader in this field is Craig Barron, a longtime Industrial Light and Magic matte photography cameraman who formed Matte World (later Matte World Digital) to create believable film environments and who now oversees 3D sets at Tippett Studio. Barron sees the transition from shooting practical matte paintings to synthesizing digital environments as a natural evolution in the filmmaker’s palette. “Unless there is a specific reason to do a painted image, as a viable tool for films today, we have moved past that,” he said. “The aesthetics and choices that went into that are applicable to what we do today. The history informs your ability to carry on with the aesthetic and how to create compelling images for audiences.”

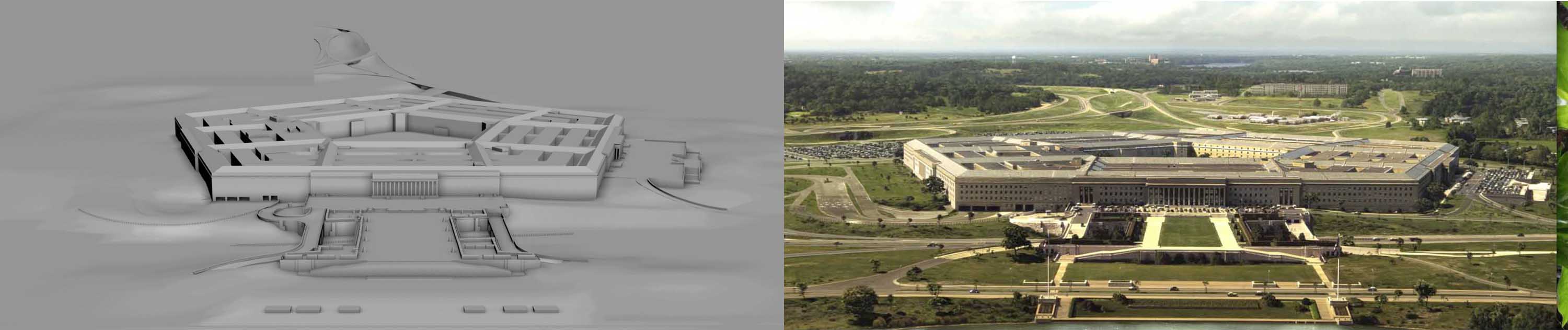

In point, Barron noted that digital tools have almost completely replaced matte paintings on canvas and glass, which were effective tools for the first round of Star Wars and Indiana Jones films that he worked on, but have not been largely implemented in more than a decade. “We can effectively simulate reality on the computer much more effectively than we used to,” he said of the new methods, but cautiously added, “There isn’t any one way of doing an image. There still is a need for thinking about how to do hybrids of imagery. If you look at visual effects movies today, there is a certain vocabulary as to how things look. [Having] a style to something could take you out of the narrative of watching a movie. The idea is not to have a style – to achieve realism. Sometimes, you can do that effectively on a computer, and sometimes you miss the mark.”

Working at effects house Pixomondo, Teresa Rygiel was integral in the creation of 400 effects shots for the Tom Cruise sci-fi vehicle Oblivion, creating everything from environments, which extended location photography in Iceland to various residences and spacecraft throughout the story. One problem they faced was that their computer-generated imagery strangely looked too clean and sharp to the untrained eye. “On Oblivion, we spent a lot of time adding lens flare, distortion, dust hits on the lens, and water hits on the lens,” she explained. “People are trying to make things look as photographic as possible. [But on Oblivion, the] CG looked too perfect. It has to look as if the camera was destroyed in making the film.

Heralded visual effects supervisor Robert Legato is an industry veteran who has worked on films by directors ranging from James Cameron to Martin Scorsese. He related the crucial aspect of practically-achieved principal photography, even on an effect-intensive film. “I always get as much in camera as possible even if it’s only for reference,” he said. “Any kind of photographic reference is great. I will shoot as much as I can in camera to lend credibility to the whole sequence.”

“When you do everything in CG, you have to put in every little story point,” he remarked. “The verisimilitude of the shot is blown when everything is razor sharp perfect. I get so much reality [in live-action] by the way that light bounces off of a subject; I believe what I’m being told. Over time, [in CGI] you get numbed by the images you are looking at.”

Legato chooses to execute his effects by whatever technique he deems the most appropriate, except on a project that dictates wholly computer-generated techniques, such as with Avatar. “Generally, I make that call, or else the call is so common, it was a fait accompli – that was how we were doing the movie,” he said. “With most directors, it’s left up to me. Most people are comfortable when you have at least something that could be considered real. We at least shoot reference. Sometimes you make that call, and when it’s not working, you have a backup. I have all fronts covered and pick and choose per shot what is the most appropriate.”

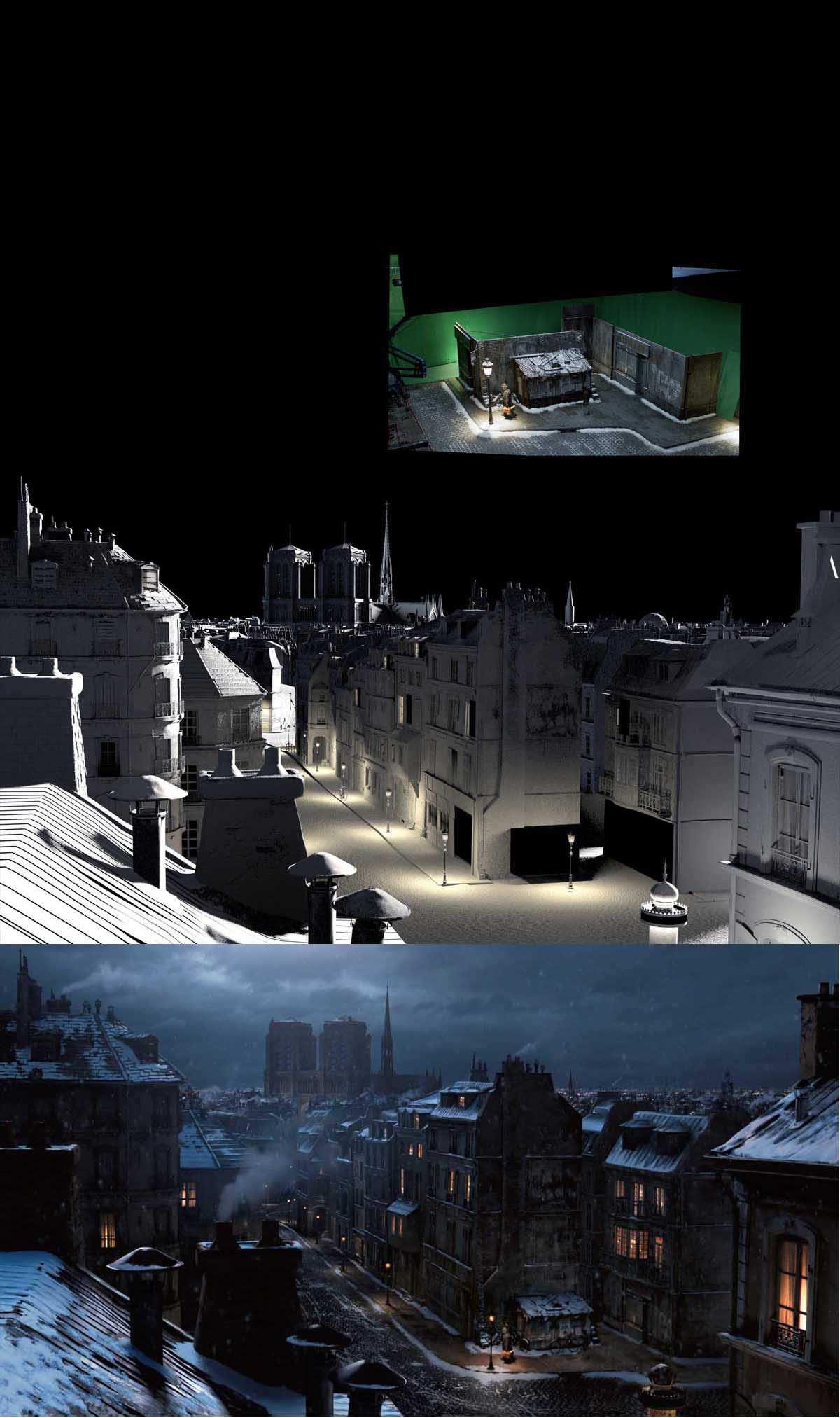

Of all of his films, one recent project stands out to Legato as his finest work. “The one that I am as proud of as any is Hugo – a hybrid of virtual sets and real sets and maintained the artistic production value in all things,” he explained. “If you didn’t know [how we did our effects shots], it didn’t matter and audiences could just appreciate the art of the movie. The goal is that the art feels the same, so you stop questioning, and you are immersed.”

On earlier projects including Apollo 13 and Titanic, Legato chose to build and shoot miniatures for the various ships and related elements onscreen. Surprisingly, for Titanic, the ship itself was entirely realized with practical models of various sizes – no digital version of that ship existed on film, where today, CGI might have been the chosen approach. “In Titanic, I matched and built miniature Musco lights to light the model ship with, so that it would have the same light and quality as Russell Carpenter’s [practical full-scale Titanic set]. I did it as a miniature version of his shots so audiences wouldn’t feel or sense a difference. They had a 100×100’ tank. We added the CG water and make it appear to be one shot — it was model photography.“

Working with James Cameron in strategizing the various techniques that they would use to sink the ship onscreen for Titanic, Legato noted that his director was very open to ideas. “He insists in designing the shots. He asks for help and talks to you like he would talk to an actor. He is going to guide you in what you are giving him. He finds the way to circumnavigate something that he’s not that fluid in. He has a very sharp eye and unerring instinct.”

Determining the literal line between practical and digital elements for films is also the domain of the production designer. For one, Robert Stromberg designed the computer-generated world of the planet Pandora in Avatar, then designed Alice in Wonderland and Oz, The Great and Powerful back-to-back with similar approaches: building partial sets on stage and extending those into cascading environments using digital tools. Stromberg’s next job after Oz was stepping into the director’s chair for Maleficent, which he finished shooting last November after 84 shooting days in England. He is now engaged in “a mountain of visual effects work,” which will lead to Maleficent’s July 2014 release.

In a hybrid approach, Stromberg co-designed Avatar with Rick Carter who handled all of the physical sets, with the digital material falling in Stromberg’s court. For Stromberg, Avatar involved an experiment in “learning how to film and create an entire world digitally. The majority of [Alice in Wonderland] was greenscreen – 70 percent. Based on what we learned from that, I approached Oz with a more even split of physical versus digital. I and the director [Sam Raimi] felt that we wanted something that the actors could touch and DP could light, with the visual effects team having a great start rather than relying on a team of people to light and construct around actors later. Having practical sets helped the director in blocking scenes.”

On Maleficent, Stromberg used the Oz model of an even split between practical and digital. “We built some gorgeous sets and digital environments. You have to create at least a portion of a playground for the crew to do their jobs efficiently, and use that as a springboard to create the world around it.”

Lastly, many former traditional matte painters, accustomed to years of choosing glass or canvas as the hard medium onto which they create cinematic worlds, have increasingly moved into digital realms. One such craftsperson is Rocco Gioffre, a practical matte painter who has not created a physical work of that sort since 1997 as he is now completely immersed in creating digital environments. “I was introduced to digital mattes in What Dreams May Come,” he said. “I sat down with the digital matte artist, and then had a hard time getting away from digital.”

One computer program dating back to a period when matte paintings were nearly all practical is still the program of choice for digital matte painters, Gioffre included. “Most artists are working in Photoshop for the painted portion and combining images together,” he said. “That artwork goes to other programs for compositing work. AfterEffects and Nuke will inherit the files we create in Photoshop and can be camera projected that can be match-moved on a set.“

Other newer programs of choice have crept into the digital artists toolbox, as Gioffre explained. “I use Cinema 4D [to bring in] my Photoshop elements. You’re painting in a number of different sections and filling in the gaps. It’s a matter of getting accustomed to the new software. The same rules apply in visual effects: you try to keep things as real as possible. My preference is towards realism.”