Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, the Denzel Washington-produced film based on the August Wilson play, is a technical delight in addition to an acting powerhouse. As previously reported, the film covers a particular episode in the famed singer’s life (played by Viola Davis), as she was trying to make a record in a Chicago studio in the summer of 1927, although the movie was actually shot in Pittsburgh. To help, she enlists a band that includes characters played by Chadwick Boseman and Coleman Domingo. But Ma Rainey is moody, demanding, and even tyrannical. She will not perform until a specific list of her demands are met, which means a lot of waiting around for the band members.

All of this amounts to a production design challenge from the get go—how to recreate Chicago and its famed L train during the 1920s, while filming from another city entirely? How to negotiate the space between the upstairs of the warehouse where Ma Rainey paces back and forth like caged lion, awaiting her moment to shine, and its relationship to the cramped, downstairs room in which the musicians anxiously await?

Last week, Below the Line spoke to Mark Ricker, the award-winning Production Designer who created Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom’s detailed sets, and whose past work is as varied and intricate as the houses in The Help and the TV studios in Bombshell. Read below what Mark had to say about how he conceived of the sets, and how those ideas played out for director George C. Wolfe.

Below the Line: How did you approach this topic after you were called on?

Mark Ricker: I had worked with one of the producers, Danny Wolfe, in The Nanny Diaries and he was the one who thought to bring me on. I quickly read the schedule and met with George in his townhouse in New York City, and he offered me the job there on the spot. I was not very familiar with her—I had a sense of August Wilson but not her, so I looked at a lot of the pictures. It curiously never occurred to me to read the play.

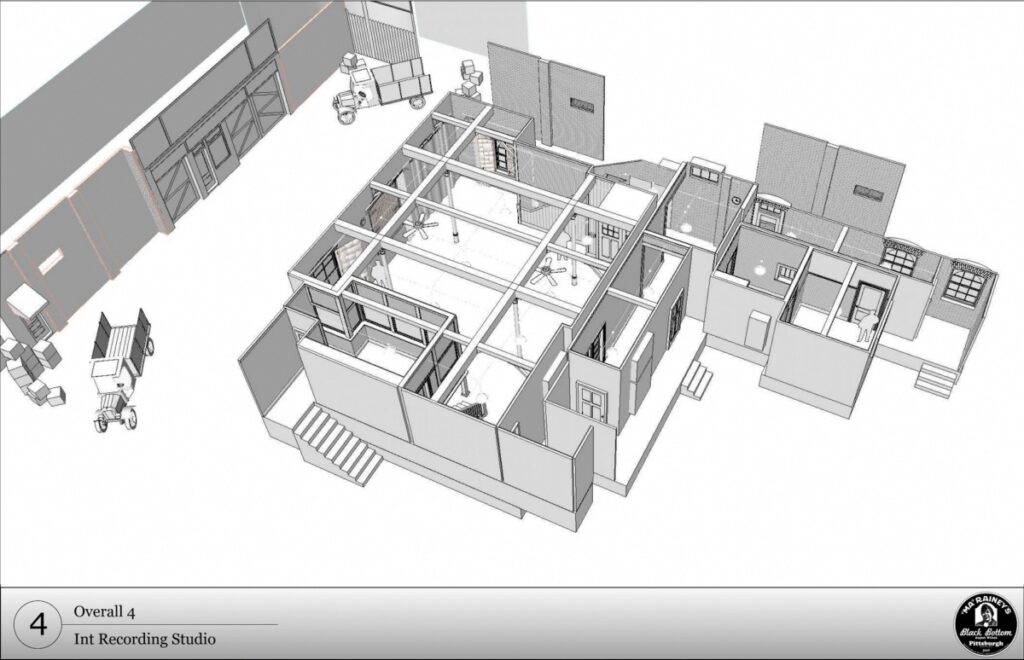

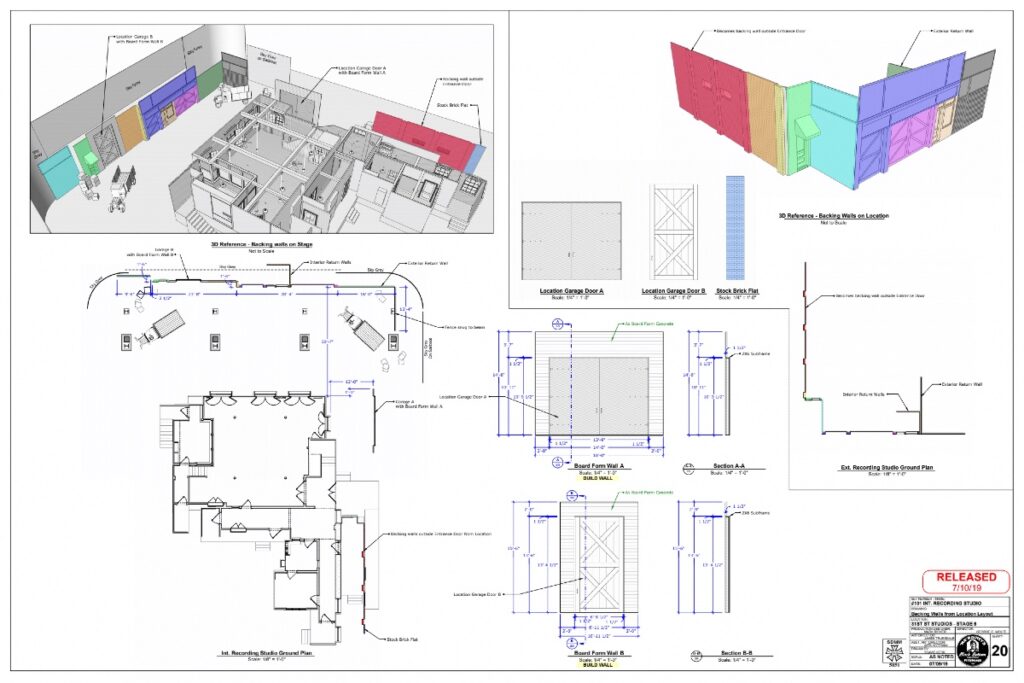

BTL: Where did you get the idea for the recording studio you ended up designing?

Ricker: Well, again, there was not a lot of material available in terms of photographs of studios. So I actually started with the recording material like the machines or the recording booths. They would inform me in terms of what was necessary to accommodate the machinery. Some of it came from loose conversations with George. We agreed that the studio would be in some old factory type of space. So my research went to that—what would a manufacturing floor look like back then? Plus in my mind I had an idea that the recording booth would actually be elevated above the studio.

They had hired a location manager, too, so there was an idea of what the building would look like, but it required a lot of work on the ground in Pittsburgh to figure out the building, as that would eventually dictate a lot of the floor plan, the location of the windows, and the like.

Eventually I did a floor plan for George, which he had a visceral reaction against. It was interesting that in the creative process his ideas and mine were not always the same at first, and we were able to get them in the same place. For example, at that point he wanted the booth much more separated from the rest of the floor.

BTL: What about the band room, how did you conceive of that?

Ricker: Well it relates to the other room as the basement, so you need stairs obviously. Some of the choices we made were conscious—we wanted to conjure up a slave ship with the bottom floor. Some of the choices were not, it just comes out of your head because it’s in there. You start drawing what’s in your head. It’s a fascinating process, you start with a deck and somewhere in there is the design of the movie you want, you just have to discover it along the way.

The band room downstairs is a good example of what the creative process is. As described in the script, it was a room with no air, no light, windowless. You read that as a designer and it causes some pause. “Okay, What is that REALLY going to be?” In this window, it was the concept of not having any windows. And I was shown by the location manager an abandoned liquor barrel warehouse, with giant timbers (some diagonal!) and multiple levels, and other signs from 19th Century architecture. It seemed very promising and we wanted to use this location.

I brought George to this location and again, he reacted viscerally to the suggestion. Ultimately, he said there was too much going on. I was trying to pitch to him that we needed more in the small windowless room—we did have 40 pages down there! I wanted to have something visually interesting but George calmly said: “The people will make it interesting.” He was so right, and it was like, “Okay, start over.” That’s typically how this process works and how it was for this film—it is always very rewarding.

BTL: Ultimately, were there any themes you put into the basement room? The room is supposed to be windowless in the play—what happened?

Ricker: We wanted it to resemble the architecture of the hull of a slave ship. I started drawing things like that—I literally looked at the shelving that would have held the bodies in a ship and thought ‘I can transform this into shelves that hold whatever item the warehouse manufactured.’ George still insisted it should be simpler. It was just a fantastic lesson for me to just listen to George. But we still had a lot of brick, which obviously wouldn’t be in the hull of a slave ship, but the timbers of the floor evoked it. The window that ended up in there could have been something in the ceiling of a hull, sort of like a hatch you would have entered through. The minimalism—the ship would have had the rafters and the bodies.

When Tobias [Schliessler] the cinematographer came on, he also expressed concerns about the lack of a window, so he supported me on that one. I just wanted anything to put in a sense of light in there. This process of discovery through everyone working together that made this worth it. But the window was important—it was the size of my computer screen. It helped too as a clear contrast to the top. We are clearly down there and it’s a little opening and up top the light can pour in. We had an archway and little cavities in the room where you can pretend there had been shelves, where the beams would have come in. It was a way to create shape in the brick and the actors ended up using them for various purposes.

BTL: It seems like windows were an important element that you used in the play to different effects, so tell us more about the ideas behind that?

Ricker: There were a lot of windows in the upstairs space but they would be recording music, so how would they deal with sound? I came up with the idea of the shutters that would be upholstered with horse hair and burlap, and they’d be shut with giant curtains across the windows that would serve as a muffling device (which I had seen in the research). We had to manage the light and sound problem. We just ended up going with the very thick fabric and Tobias to his credit ended up embracing it and loving it. In the film you see them slam shut the curtains and it becomes this tomb with no light, which becomes as a dramatic device that happened organically and then when Ma says ‘I’m not recording’ then they open up the blinds, so the spaces can change quickly with that device and we liked that.

BTL: Talk to us about the outside sets—you were in Pittsburgh, pretending to be in Chicago.

Ricker: George wanted to go to the city and show how disconnected it would be for Ma. No black people. No greenery. No element of humanity, just colder steel. So we put up the elevated train, we created the corner of Brownsville (which was a thriving neighbor in Chicago where the affluent black community lived). There was a difference in the spirit and visuals of what the two neighborhoods would look like. This, too, comes from research, and we had much more material for that.

We had details in our head about what made something Chicago-specific. We did recreate the elevated train. We even recreated the trashcans with advertisement on them (thanks to the graphics department). That showed you different sections of the city. There was more jewel colors in Brownsville. We used a lot of wood outside and plank wood and beat board—as we had inside actually. We wanted to have a texture that was interesting for people to look at.

BTL: How did you work with the colors? How did you land on those?

Ricker: Well, it was a limited palette. We had that green. Even though it’s a movie, it’s an August Wilson play that does not exist in the truly real world. We wanted to create a background for the actors to be in that was like the stage of a play.

BTL: How did you feel about the film as a finished product, how it all came together, how it looked?

Ricker: I was recently watching a brilliant interview with Mike Nichols, where he discussed fighting with Jack Warner to shoot Virginia Woolf in black and white. He explained its importance to him because black in white in film functions as automatic metaphor. I was so taken with that idea. Which I thought spoke to what I was doing – unconsciously really – with the limited palette for the film. When I first saw the finished film, I thought it felt like an old fashioned film in the best way, and I think some of that was that it almost felt like a black and white film, in color. And I do think that because the source material was August Wilson’s play, so many of its themes were epic and metaphorical, and so that limited palette supported the idea of those themes and ideas. I did that on purpose without even knowing the full sense of what I was doing.

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom is now available to stream via Netflix. You can read our previous interview with the Makeup and Hair Team and with Director George C. Wolfe. Look for our interview with Cinematographer Tobias Schliessler later this week.

All photos courtesy of Netflix and Mark Ricker. Click on images for larger versions.