“I had the project sitting around for quite a while,” Ward said. “The producer who had adapted the wonderful Richard Matheson [story] had had it for 20 years and had not been able to get it made. Ron Bass did a draft which was very powerful with emotional truths about relationships.”

Given Ward’s own art background — he recently had a solo exhibition in Shanghai and has had six exhibitions in 24 gallery spaces — his first pre-visualization concepts came naturally. “The way I approached the film is I created a look long before anybody came aboard, and for two years in the script development with my screenwriter Ron Bass,” he said. “Everything had a visual concept.”

With Bass’s script in hand, Ward devised a method to render the afterlife which Matheson described onto celluloid. “I thought that there was no way of visiting that world,” Ward said, frustrated with his lack of progress. “I didn’t want to do it and put it away for a month. One day, I had an idea – the wife [played by Annabella Sciorra] was a caterer. I thought, ‘What if you turned her into an artist?’ The Robin Williams character could discover an afterlife with her paintings – that gave me a whole language for the afterlife.”

With Bass’s script in hand, Ward devised a method to render the afterlife which Matheson described onto celluloid. “I thought that there was no way of visiting that world,” Ward said, frustrated with his lack of progress. “I didn’t want to do it and put it away for a month. One day, I had an idea – the wife [played by Annabella Sciorra] was a caterer. I thought, ‘What if you turned her into an artist?’ The Robin Williams character could discover an afterlife with her paintings – that gave me a whole language for the afterlife.”

Not only did the concept of painting inform Ward’s story approach, it would affect many aesthetic elements in the film. “It would also give me a language through which they could communicate,” Ward said. “You would see something appear in his world in the afterlife – a [paintbrush] stroke. Something could happen in his world which could affect one of her paintings.”

With the device of painted materials secured, Warned next needed a visual concept for the myriad effects. “How do you realize that?” Ward asked. “There wasn’t the technology at that time to realize a world of living paintings. I hadn’t seen anything done before that was at all like what I had in mind. We took it to ILM and they did a test, but we didn’t really respond to that.”

By the mid-1990s, visual effects had progressed in films such as Jurassic Park and its brethren Starship Troopers, but the photorealistic landscapes of Avatar and Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland were still a decade from coming to fruition. “I had a fairly big budget, but we didn’t want to spend a fortune on visual effects,” Ward recalled. “Joel Hynek ran Mass Illusions, which had adapted missile tracking technology. They believed that they could adapt paint strokes onto film. They did six months to a year of development and tests, even while we were shooting. Since then, it is used in visual effects throughout the film industry.”

By the mid-1990s, visual effects had progressed in films such as Jurassic Park and its brethren Starship Troopers, but the photorealistic landscapes of Avatar and Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland were still a decade from coming to fruition. “I had a fairly big budget, but we didn’t want to spend a fortune on visual effects,” Ward recalled. “Joel Hynek ran Mass Illusions, which had adapted missile tracking technology. They believed that they could adapt paint strokes onto film. They did six months to a year of development and tests, even while we were shooting. Since then, it is used in visual effects throughout the film industry.”

Though Hynek and Mass Illusions were tasked with manifesting the afterlife as Ward proposed, the director’s use of digital technology was based on pragmatic artistic choices. “It’s great to have some sort of technological breakthrough, but it’s a waste of time if it doesn’t convey what you want to convey,” Ward said. “For me, I’m eternally grateful for the technology, but the biggest breakthrough was trying to find a marriage between technology and painting — trying to find a language between film and paint, and trying to make it look damn good.”

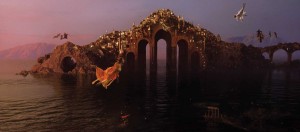

With Hynek as visual effects supervisor, Ward set about to envision What Dreams May Come’s phantasmagorical worlds. “The next thing was to get the production designer and a team of artists and illustrators and visual researchers and really research the hell out of it to see what it was going to look like,” Ward explained. “This was pre-pre-production. It was a couple of weeks to get a vocabulary so that it would have a unity to it. That is one of my strengths – finding a visual concept and bringing a world alive.”

During production, Ward took the cast and crew to Montana, to shoot live-action scenes on location with particular greenscreen elements for the section of the story when Williams’ character first reaches the afterlife. “[We would] remove the actors, paint the background digitally and track it, and then put the actor back in it,” Ward said. “It was designed to be actor-friendly. Other areas of the film had a more traditional solution with more sets. We used a studio, mammoth green screen, and artificial body of water. With visual effects, the key thing is trying to find a voice for the film that supports the narrative.”

During production, Ward took the cast and crew to Montana, to shoot live-action scenes on location with particular greenscreen elements for the section of the story when Williams’ character first reaches the afterlife. “[We would] remove the actors, paint the background digitally and track it, and then put the actor back in it,” Ward said. “It was designed to be actor-friendly. Other areas of the film had a more traditional solution with more sets. We used a studio, mammoth green screen, and artificial body of water. With visual effects, the key thing is trying to find a voice for the film that supports the narrative.”

As principal photography wrapped, Ward had a plan, but the exact effects that would represent the lead character’s journeys through various locations after death were far from decided. “It wasn’t until three quarters of the way through the editing that I managed to augment the existing themes and find a voice for the visual effects side of paintings,” he said. “I am aware now that most visual effects companies insist on a production designer going through post, trying to envisage the world and make it real.”

In the final work, What Dreams May Come combines the otherworldly métiers of classic Matheson with a distinct cinematic touch. “I’m very interested in the intimate within something epic,” Ward noted. “We were searching for it in the way that performances were filmed in relation of the world to the environment. The value of What Dreams May Come brought certain ways of working with digital and creative in order to realize a cohesive vision. That was one of the things that we were successful at.”

Looking back on What Dreams May Come, Ward is proud that its innovations have since become timeless. “Films seem to have a certain life to them long after they are made,” he said. “When you explore at a gut level and subconscious level, if you are honest, those stories stay on somehow. That’s what I’m about.”