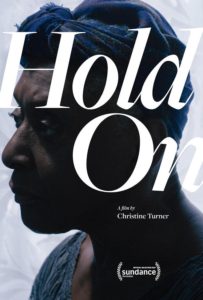

Although Hold On (Sundance) was merely nine minutes long, it packed more of an emotional arc than many feature films. Director Christine Turner had worked as a hospice volunteer in New York and drew upon her experience and observations of dementia patients to write the touching story of a young millennial tasked with caring for his ailing grandmother in a moment where they must figure out how to communicate with each other.

After working on a number of shorts together, Turner and cinematographer Marshal Stief have developed a language and shorthand together. Both have a strong interest in story and community. Turner likes to tell a story in “as few shots as possible.” She also likes to hold on shots to give the audience time “to absorb” the moment.

One of the challenges in the film was shooting the culminating scene in the cramped space of a bathroom. In addition to the aesthetic that she was looking for in the bathroom, Turner took lighting and camera placement into consideration when scouting locations. She was interested in using natural light. Because of the tight quarters, Marshall shot through the doorway. When he wanted to get closer, he used a handheld camera.

The biggest challenge was shooting the film in one day. The actors rehearsed and were well prepared. The single location made the logistics of filming possible while working within the available resources.

Documentary editor Aljernon Tunsil edited the narrative short. Turner had worked with him on a series of short non-fiction films for director Stanley Nelson. The editor was excited to take on a film in fiction realism and, according to Turner, “brought a sensibility.”

Mark Henry Phillips composed the score and designed the sound with an emphasis on supporting character. The closing song, “Hold on (Just a Little Bit Longer),” provided a critical story element to the conclusion of the film, serving as a key to the grandmother’s memory, as well as a way to bring grandson and grandmother together.

In Suck It Up (Slamdance), lifelong best friends head to the family cottage in the mountains, rediscovering their friendship as they learn to cope with the grief of losing the man they both loved. For her second feature director Jordan Canning tapped into personal tragedy to bring the emotional journey of her characters to the screen with naturalistic realism and humor.

Although Canning did not write the script, she worked closely with writer Julia Hoff to refine the screenplay and find the emotional arcs. The initial vision for the story was to follow two characters on a painful, emotional journey.

The director wanted a naturalistic, handheld camera. Working side-by-side with Canning to set the look and tone of the film was cinematographer Guy Godfrey who approached the lensing from a story perspective, never from flashy shots.

“It’s always about what is the center of this scene. What are we trying to get across for these characters? How can we do that visually?” explained Canning. “Guy and I found real, creative kindred spirits in each other.”

Because they had a small crew, the company was on the ground with the two lead actresses for about two and a half weeks before rolling cameras. The team was able to go through the entire script, take photos, and figure out the look, shots and approach. They were able to consistently stick to that vision, while still being open to explore new ideas on set and “find things in the moment.”

Because they had a small crew, the company was on the ground with the two lead actresses for about two and a half weeks before rolling cameras. The team was able to go through the entire script, take photos, and figure out the look, shots and approach. They were able to consistently stick to that vision, while still being open to explore new ideas on set and “find things in the moment.”

“The brass tack questions are out of the way and you can really work on the fine, paint brush refining moments of each scene,” shared Canning.

The director spent a majority of her time with up-and-coming editor Simone Smith in the intense re-crafting of the story. “You have the script, then Guy and I turned it into this film. Then we’re done and Simone and I turned it into this other film,” remarked Canning.

The filmmakers kept going through the edit, striping out the things that weren’t working and painfully letting go of things that they “loved dearly.” The director admits that it would be nice if you could determine what would not be in the film while shooting, but it never works that way. Even though a scene or moment might work on the page, it is necessary to see those sections as part of the whole, with all the nuances of performance and the story world, before being able see what is necessary to shape the final form of the film. The initial assembly was two hours and seventeen minutes. The finished film runs about ninety-nine minutes without credits.

“Maybe one shot tells the story of a scene and you don’t need any of the dialog any more. You just cut it all out,” commented Canning. “That happened a lot.”

The biggest challenge, and in some ways the best thing about the film, was the convergence of experiences in her real life with the experiences of her characters. The struggles with grief that she shared with her characters was at times intense, but at the same time rooted her in the project more than with any other project, even ones she has written herself.

“The subject matter has never been so ingrained in my blood. I knew what the story could be and what I could bring to it since I was living a lot of it. It was quite cathartic to bring these things to the story. We rooted these characters in the real circumstances,” revealed Canning. “Yeah, there’s comedy and raunchy fun, but always these two are struggling with their grief. What I worked really hard on in the script, and while we were shooting, was to insure that the film was true and honest. I think that’s why this project came into my life.”

Cortez (Slamdance) co-writers and actors Cheryl Nichols and Arron Shiver wanted to work on a play together. They talked about ideas, told each other their life stories, and found things in common that eventually developed into the screenplay of a musician on the decline who seeks out an old flame in a small New Mexico town, and in the process must faced the mistakes of his past.

When it was decided that Nichols would also direct the film, she brought on cinematographer Kelly Moore who she had worked with on several small projects before bringing him on to shoot Cortez. They had similar tastes, liking many of the same movies.

“We had a really good chemistry,” said Nichols. “I really liked his eye. He has such a good esthetic. I really trust him.”

Most of pre-production was done in Los Angeles. By the time the company got to New Mexico, they had a mere three weeks to prep the shoot. Because she was acting as well as directing, Nichols was very prepared, storyboarding the entire film. She also worked out a palette of colors that changed from morning to night. The director spent a lot of time in pre-production going through all her ideas with the cinematographer so that he knew exactly what she wanted to do. They re-configured what she wanted with what was possible.

Since producer and acting location manager, Johnny Long, knew Taos very well and sent pictures, Nichols had an idea of where she wanted to shoot scenes before production started. The company had a few curve balls, but those instances gave the movie “a lot more character.”

“Sometimes when you don’t plan for something, it’s a lot better than when you’ve got some stupid idea in your head that you think is brilliant,” admitted Nichols. “I’m not too proud. I’ll lose it, if it needs to go. I’m well versed in killing babies.”

The film was almost completely handheld. The director would use a tri-pod if necessary, but she preferred a lot of movement. She liked the camera “to feel like another person” and talked with Moore about how important it was to her that he was “another actor in the scene.”

The production shot for three weeks, with a strict policy of ten-hour days. A few exceptions were decided well in advance. The director felt she would only get ten hours of good work from both cast and crew.

Because the film was a performance-based piece, the actors rehearsed quite a lot in advance of filming. One intense scene was twenty pages long, but the performers were theater actors “in for the long haul.” Nichols felt shooting the film was a lot like shooting a play.

Post continued for about five months and began after the shoot ended, partially because the filmmakers had to find their post budget. Once they had the funds they started editing. Nichols, who has been editing for a while, worked under the pseudonym, F. Rocky Jameson. As extra sets of eyes, Nichols used a couple of people, including a trusted editing friend, to get story notes. When both gave her the same comment, she re-edited based upon those points. The original cut was 2 hours long, eventually edited down to 99 minutes.

“When you are so intimately involved with that kind of movie, it is really difficult to edit,” stated Nichols. “At the same time it’s got to be your thing. You’ve got to do it. Part of me was trying to create a rhythm that only I knew how to do. I couldn’t communicate it well to an editor. Maybe that’s my bad.”

The biggest challenge of the film was the three-week shooting schedule. Nichols would have spent more time on some areas, if she had the extra time, but she noted that more time is probably the preference of most filmmakers.

Nichols credited her entire crew – about fifty percent were women – for making the film possible. Of special note, Nichols mentioned Keith Jones, the camera operator who had to run backwards with the Red camera on his shoulder, Carl Lucas, one of the producers who stepped in as assistant director, make-up artist, Colette Tolen, production supervisor, Andrew Aguilar and the female key grip, Jeanette Loera.

“It was a small crew, but all of them were great.” Nichols concluded, “If one of them had been gone, the movie would have fallen apart.”