As soon as I finished watching Showtime’s new Bill Cosby docuseries, I knew I needed to talk to W. Kamau Bell, the insightful comedian who directed We Need to Talk About Cosby.

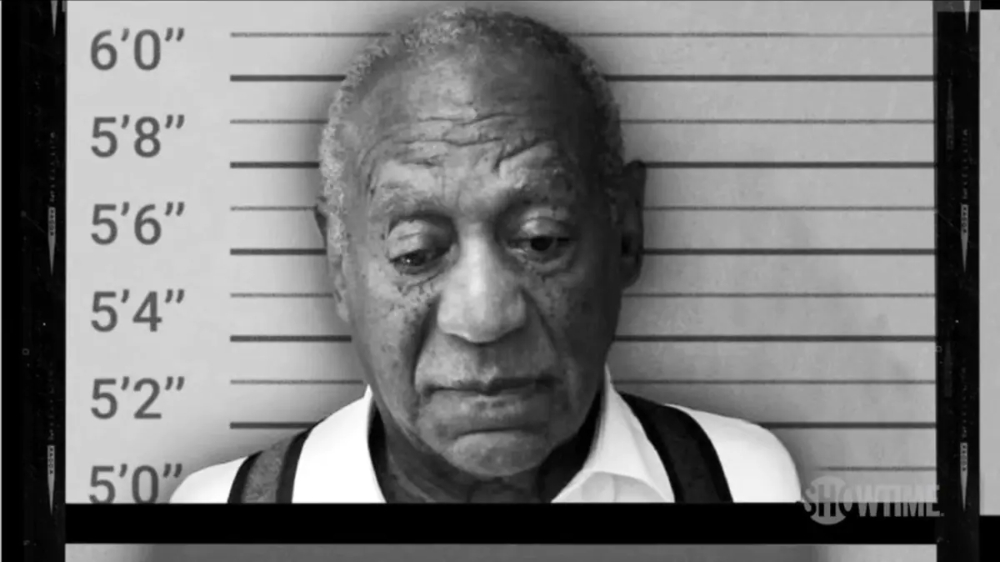

Bell’s four-hour documentary or “cultural anthropology,” as he calls it, examines the sordid allegations against Cosby, who went to prison for drugging and sexually assaulting multiple women. His conviction marked rock bottom for the disgraced comic, who appears to have left a trail of not-so-subtle breadcrumbs in his work over the course of his 50-plus-year career in film and television.

Like Ezra Edelman‘s acclaimed docuseries O.J.: Made in America before it, We Need to Talk About Cosby made its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival, where it ended the week as the most gripping and urgent project that I saw, marking Bell as a documentary filmmaker to watch.

Bell spoke to Below the Line in advance of the series’ debut on Showtime, where the first episode is currently available, with the remaining three due to air over the next few Sunday nights. Please check out our nuanced conversation below, as it was both thoughtful and illuminating, especially seeing as how the director still describes himself as a fan of Cosby’s work. That kind of honesty is rare, folks.

Below the Line: What was the spark that made you set out on this endeavor to make a Cosby docuseries, and was it always conceived as a series, or did you ever consider making it a feature?

W. Kamau Bell: The spark was, I was born in the early ’70s. That was the spark. I was a Black kid and I cannot remember a time in my life when Bill Cosby was not a part of the wallpaper of Black America. And also, for years of my life, he always was an unimpeachable source as an example of ultimate morality and ultimately, someone you wanted to aspire to be like, and also someone who was very funny and did good works in the world. So that was the spark. ‘Oh, this is who I believe this person to be.’ And then, as a Black kid who decided to become a stand-up comic, who was very much inspired by Bill Cosby himself and very much watched The Cosby Show every week, the spark is that I thought I knew who Bill Cosby was, and to quote Kierna Mayo, “we thought we knew Bill Cosby. We never knew Bill Cosby,” is how I feel about it.

But then, as I started to “make it” and get interviewed by major media, and they would ask you the things they’d ask new comedians or comedians who are new to them, ‘who are the comedians that you liked as a kid?’ And it was the same time that allegations were starting to come forward a lot more, and more and more women were coming forward with these allegations, and I was like, ‘how do I not say Bill Cosby, because that would be a lie? But how do I say Bill Cosby, because [now] there are all these stories we have to reckon with?’ That’s when I started to feel like, ‘we need to figure this out,’ and that was well before he went to prison.

And then once he goes to prison, it became, like, ‘maybe we’re ready for this complicated Bill Cosby conversation,’ and when I started talking to my team and the people I work with, it was always, like, ‘we can’t cover this in two hours. He has an over 50-year career on camera, and at the same time that was going on, there are women who accused him of sexual assault and rape throughout that same period of time. And two of the touchstones for this documentary are Ezra Edelman’s OJ: Made in America, which is a 7.5-hour documentary, which is 7.5 hours of O.J. Simpson, which you never thought you wanted until you saw it, and Dream Hampton’s multi-part series Surviving R. Kelly, which in painstaking detail says, ‘this is an active crime scene and we need your help in catching the criminal.’

BTL: I love that O.J. documentary. I think it’s the best thing I’ve seen in the past decade.

Bell: For sure. It’s a great piece of art, I say, like, if you go see the Sistine Chaple, you should probably also go see OJ: Made in America.

BTL: Did you reach out to Cosby for an interview?

Bell: No, when we started this he was in prison, and it was also never conceived as, like, ‘we need to talk to Bill Cosby,’ because Bill Cosby has been clear about his side of this and what he wants to say. And once he got out of prison, he was talking about making his own documentary, and by then we were so far into it that there was no room for him in this doc. It also, honestly, would’ve felt like a betrayal to the survivors to say, ‘we’re going to give you space to tell your story in ways you don’t normally get to tell it, but also, we’re going to have a conversation with Bill Cosby where he’s going to say the things we’ve heard him say before.’

BTL: Given that fact, do you worry at all, as a filmmaker, that the series will be perceived as one-sided in some way?

Bell: You know, as a standup comic, I’m used to things being one-sided. This is the way that standup comedy works. We only say ‘what do you guys wanna talk about?’ when we forgot what the next joke is. I think that one way we sort of talked about this early on, and Vinnie Malhotra from Showtime was great about this, was like, ‘this is actually like an op-ed.’ An op-ed is supposed to have the journalistic standards of the newspaper, but it’s also supposed to have the opinion of the writer. It’s not true-crime because it’s not trying to solve the case, so I think if this was a true-crime doc, then I’d say we need to talk to all parties, but it’s not true-crime. It is a cultural anthropology.

BTL: Do you think a white comedian or a white documentary filmmaker could’ve done justice to this story, or did it need to be told by a Black filmmaker who grew up worshipping Cosby? Because for me, a big part of why this resonated so much for me is because it wasn’t about our collective disappointment with Cosby, it’s about yours.

Bell: So I remember back in the late ’80s/early ’90s, there was talk of a Malcolm X movie, and at that point, there was a white director attached to it. And Spike Lee advocated for the fact that not only should he direct it, but definitely a Black filmmaker should direct Malcolm X, because Black people have a different level of facility and accessibility and understanding of the material than a white director would. And the best argument he made for that was, ‘you can’t tell me that Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola don’t bring something as Italian-Americans to Goodfellas and The Godfather and those types of movies. And so I feel like the same thing is true here.

It is definitely because of me, in many parts, it’s a story of Black people and Black America and our struggles to understand this. Now, we also incorporate other perspectives, because that’s also what Black people are trained to do in this country, is make sure to know what else is going on, but in the same way that if one of the survivors had made this doc, it would be very different. And all of those things maybe should happen, but I certainly think there is something that happens because I am a person, as I say early on, who considers himself to be “a child of Bill Cosby.”

BTL: Since this is Below the Line, can you shine a light on some of your team? For example, your editor, who I imagine had to wade through a ton of footage, or the people who helped give each interview its own distinct look and style?

Bell: So I think below-the-line, if we’re going to talk about that, COVID is affecting everything across the world, and also specifically affecting TV production and entertainment media. So there is not a “the editor.” We started working on this in one period, then COVID hit and we shut down, a lot of the editors we thought we had had moved on, then we filled in with editors who said ‘I can do this for a couple weeks,’ ‘I can work on this for a period of time,’ and then you find an editor who’s like, ‘I can be here for the long haul,’ so it was very much a huge team of people who had their hands on this, and it’s very interesting that I can look at this and go, ‘that editor was around for maybe six weeks, but that’s their work.’ So all that work is still in there, and we sort of figured out, well, ‘what are your strengths?’ ‘Oh I’m good at the stuff that’s, like, fast-moving, or moves to music,’ or, ‘I’m good at the survivor interviews.’

So it’s amazing how many people worked on this and how many people touched this, and for me, that it doesn’t feel like that, I don’t think. It feels like one editor the whole time. Now we did have one editor with us the whole time, Jen Brooks, and her hands touched every episode in one way or another. She’s the one who I’d say was there from the very first day till past the last day.

And then the other part for me is that it was important to make sure people were working on this, who are… part of this is, it’s always about representation and including people who don’t always get these opportunities, so one of the producers is named Geraldine Porras, who I met as a film producer on United Shades of America, and she’s a young Latina woman, and at the time when I was working with her, I could see how the industry was putting more work on her and giving her less credit, and it was happening on the set of my show, so I observed that and I created more space for her, I made sure she got promoted, and when we won our second Emmy, she gave a speech at the Emmy Awards, and she’s also one of the co-EPs on this project.

And what that meant on this project is that one of her jobs was to actually stay in touch with the survivors and reach out to the survivors, and during COVID when we were shut down, the survivors still wanted to know what was going on and when we were going to start up again, and that’s where a lot of unpaid labor goes on, which women of color are very experienced with, so she did a lot of the unpaid labor of keeping this project afloat.

BTL In the editing room, who was the person whose insight into this case really stood out to you, because for me, it was Renée Graham of the Boston Globe. I thought everything she said was gold.

Bell: Yes! Yeah, I mean, you know, some people know how to speak in quotes, and Renée just showed up ready for business. She is a great person, she’s a fun person, and she is not screwing around. So it was very clear that she was like, ‘I am here to say what I’m here to say, you can ask me whatever question you want to ask me, but I am not moving off my line.’

And I really appreciated that because we needed different ways to communicate this information, and some people have a lot more conflict in their voice, even if they support the survivors and even if they believe these women’s stories, but she is not conflicted in any way, and it makes sense that somebody who is a born-and-raised New Yorker and ended up in Boston deals well with conflict.

But yeah. she was somebody who we had later in the process, when it became very clear from that interview, ‘oh, we’re going to have to go back and open things up because she needs to be in this throughout.’ I look at a lot of the people we talked to and there are so many voices that you don’t see in this format, and I feel like all of these people, except for Cosby, we need to see more of these people talking in other formats.

BTL: Why do you think Cosby fans are so convinced of his innocence despite dozens of women coming forward with the same story, showing clear evidence of a pattern of behavior, and that it wasn’t a one-off thing?

Bell: I mean, it’s so funny because it’s like, I think I’m still sort of a Cosby fan if I’m talking about the work. I mean, this is complicated, so that’s my feeling here, and you can feel my love for the work in this. I think a lot of Cosby fans are like me, they’re conflicted, where I support the women and I believe the women, but I also know that somewhere inside of me, coursing through my veins, is the work that inspired me.

But on top of that, I would say there are many, I would call them “Cosby defenders,” because I think it’s a step more than being a fan. I think that for some people, there is a sense that anytime that a black man is accused of a crime, they are apt to not trust the accuser, and I think some of this has been weaponized, so many are using the fact that many of the survivors are white women to act like all of the survivors are white women, and that falls into a very convenient narrative that we talk about in the film [in reference] to Emmett Till. Renée Graham talks about this.

So there are some people who say, ‘I am just suspicious of the justice system,’ which I understand, and I try to say in the film, ‘I understand.’ I’m not trying to leave that behind. And then I think for some people, they haven’t actually done the work, as you would say. They’ve read the headlines, and it’s not fun work to do, so they’ve sort of avoided the headlines, or they’ve had arguments on Facebook, and it’s not like they’re bad people, but there’s a lot going on in the world and it’s not easy to do this work, so for me, as I do in my career, it’s like, ‘hey, let me do the work for you.’

So this film is really aimed at people who are like, ‘I feel conflicted about this. Maybe I don’t believe these women but I still feel conflicted about it, so let me sit down and actually watch this, and maybe after watching this I will come to a new understanding.’ For me, as much as I believed the women, I didn’t know that Cosby had said in his disposition that ‘I entered the area between permission and rejection’ while he was talking about drugging Andrea Constand. And to me, that’s the moment when I read it that I was like, ‘I rest my case, your honor.’ What do you say past that? Reasonable people know there’s no area between permission and rejection, so Cosby’s own words, in many ways, have indicted him. And I think once we put this out and lay it out for you, if you don’t believe it by the time we get to the end of this, if you haven’t created more empathy in your heart for these survivors, then there are people who just refuse to do it, and I can’t really worry about you. But most Americans are reasonable if ill-informed.

BTL: With Cosby being let out of jail early, do you think he paid a steep enough price or did he deserve to rot there?

Bell: I think [inaudible] who we talk to in the doc, really talks about the idea, and also Eden Tirl talks about this too in the doc, is that prison is not necessarily the solution, and that’s why I think this documentary wants to get to a place of talking about this in a more holistic way. Prison doesn’t do anybody good, generally. If you are rehabbed in prison, it’s usually because you did the work yourself to rehabilitate yourself.

I live in Oakland and hang out with a lot of prison abolitionists who say, ‘the whole criminal justice system is not designed to heal people’ There are many countries who do a better job of that than us. So I don’t necessarily think him rotting in prison does any good, I just want him to do no more harm and in the current society, the only tool we have for that is putting people in prison.

BTL: Did you reach out to Hannibal for an interview?

Bell: Yes, I did, as I reached out to many people. It’s very clear in the interviews with Hannibal that he doesn’t really want to talk about this. I reached out thinking maybe he’ll talk to me because I know him a little bit, but he didn’t want to talk to me and I totally accept that and understand, because Hannibal has never wanted this to be a part of his career and legacy if you’ve seen any of the work that Hannibal’s done since then.

Some comedians, this would’ve been a turning point in their career, like ‘oh, I’m the guy who took down Cosby,’ and that’d be the name of the tour, it’s on the t-shirt, it’s a hashtag. But Hannibal’s like, ‘I just wanna act and tell jokes. That’s it. I don’t want to do this.’ So I don’t begrudge Hannibal [for not being] in this film.

BTL: What’s next for you? Are you still focused on your comedy career or are you looking to do more filmmaking now, and if so, do you want to stay in documentaries or would you like to tackle something scripted?

Bell: Well you know I’m still doing this day job called United Shades of America, this is like my weekend job, so yeah, I’m still doing United Shades of America and we’re in the middle of production on Season 7, but yeah, I do want to do more documentary filmmaking and there are already other projects that I’m beginning to work on. But they’re not all, believe me, they’re not all ‘we need to talk about this problematic thing,’ I have more interests than that, but they are always going to be in areas about, like, ‘how do we create more space, more equity, more justice and more joy?’

We Need to Talk About Cosby is currently available on Showtime.