In his feature-length documentary Memory: The Origins of Alien, director Alexandre O. Phillipe examines the early formation of the beloved 1979 sci-fi classic Alien on the occasion of the film’s 40th anniversary. However, at the outset, Phillipe wanted to relegate his film to one specific unforgettable moment in Alien.

In his feature-length documentary Memory: The Origins of Alien, director Alexandre O. Phillipe examines the early formation of the beloved 1979 sci-fi classic Alien on the occasion of the film’s 40th anniversary. However, at the outset, Phillipe wanted to relegate his film to one specific unforgettable moment in Alien.

“Initially, it was a desire to explore the chestburster scene the way I did the shower scene in Psycho [in the documentary 78-52],” Phillipe proclaimed of his renowned dissemination of Hitchcock’s notorious ‘shower scene,’ realizing that unveiling Alien’s secrets was a fully separate exercise.“The key to understanding the chestburster is delving into the mythological underpinnings of the film itself. It came out of [screenwriter] Dan O’Bannon’s unconscious and [conceptual artist and creature designer] H.R. Giger. It resonates with our collective unconscious.”

After he had initiated pre-production work on Memory, Phillipe realized that he had to broaden his understanding of O’Bannon, leading him to connect with the writer’s widow, Diane. “My encounter with her changed completely the complexion of the film,” Phillipe revealed. “I was still trying to figure out what Memory was about. The day I got into her archives, it changed [everything]. Without O’Bannon, there is no Alien. Memory had to really get into O’Bannon and his story.”

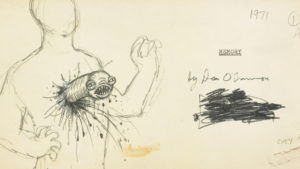

Indeed, Phillipe learned—and shows viewers—the critical nature of O’Bannon’s work on the early version of the Alien script, called “Memory” at the time. He also researched obscure influences on Alien, including Defiled, an underground comic from 1971, leading Phillipe to track down Defiled’s creator for an interview about its impact on O’Bannon’s first ventures on Alien.

“He was really shocked that people remembered that particular connection,” Phillipe said, noting he worked alone for a bulk of his film. “Once you start connecting with people who are in the know, the information bubbles up to the surface.”

Once Phillipe began digging into O’Bannon’s archives, he discovered that 95% of the material had never before been shared with the public, including different early versions of the screenplay. “‘Memory’ was only 30 pages — a remarkable blueprint to the first act of Alien,” stated Phillipe, noting that he also located O’Bannon’s group of alternate endings. “Diane is one of our executive producers, deservedly so; she really gave full access to the archives. Without her, there is no movie.”

Among the revelations in the movie were the fact that O’Bannon had Crohn’s Disease, which eventually killed him at a young age, and had been studying parasitic wasps, two elements which surely figured into the machinations of Alien. “The idea was in Dan’s unconscious,” Phillipe related. “My opinion is that Dan O’Bannon is the author of Alien. The first draft is Dan O’Bannon with Ron Shusett—they both have story credit. [Screenwriters and producers] Walter Hill and David Giler did make improvements to the story, but they are not the authors.”

Once the Alien script was in motion, Phillipe points to the supreme presence of Giger in the design and execution of the film, plus, unquestionably, director Ridley Scott, in bringing the film to life. “Alien would not be Alien without O’Bannon, Giger, and Scott,” Phillipe claimed. “Those three are the foundation of Alien being the film that we know. There’s many other contributors, [but] you remove Dan, Giger, and Scott, and there is no Alien.”

In fact, Phillipe notes in Memory that O’Bannon pushed for Giger’s vision to be included in the execution of the film. Even when studio bosses sought to dismiss Giger from the project, Ridley Scott fought for him to stay on board. “He believed that Giger needed to be an integral part of the project,” said Phillipe of Scott. “That’s what great directors do. Ridley Scott recognized what he had—he pushed for it and insisted that [Giger] be a part of it. Ridley Scott is the savior of Alien.”

Moreover, even though O’Bannon was broke when pre-production work began on Alien, he believed so much in Giger, O’Bannon paid the artist $1000 out of his own pocket to keep him on the project. “It shows you what kind of guy O’Bannon was,” said Phillipe. “He was the visionary behind it and pushed it in front of Ridley. Dan paid for those early drawings and paintings when he didn’t have the money to do so.”

With regards to Swiss legend Giger, Phillipe showcases the artist’s singular visual world, one which taps into a collective unconscious, with specific links to Egyptian mythology. “The imagery is very charged: psychologically, sexually, evocative to the nth degree,” Phillipe expressed. “The imagery of the world that Giger creates evokes so much beyond what it shows us, and makes your mind and imagination connect with the film in different ways. Only a great artist can do that.”

Unexpectedly, via a narrative opening sequence in his film, Phillipe creates a symbiosis between the ancient past and Ridley Scott’s Alien. “It announces itself—it contains all of the ideas and the themes that are important to what I’m trying to express in Memory, in a visceral way,” Phillipe confessed, nothing that he attempted to start building questions in the mind of the audience in Memory’s first several minutes. “What is the connection between the ancient world and the future? There are stories and images that we revisit culturally at certain times—those stories are perennial. What the sequence does is establish a major dramatic connection.”

Ultimately, Phillipe sees his film Memory as a fitting companion piece to Alien. “Any film buffs will find so many ways to re-approach Alien and see it through a fresh lens,” he said. “People who are newbies will appreciate it—anybody can have a whole lot of fun dissecting movies. It should connect and does connect for not just cinephiles, but for the general audience. In Memory, the passion is palpable. I think a project like this can only be good for Alien and the franchise. It was one of the rare Hollywood movies that was ahead of its time.”