Cinematographer Newton Thomas Sigel, ASC has executed more than 70 film and television projects. His vast filmography includes Da 5 Bloods, Bohemian Rhapsody, Marshall, Drive, Superman Returns, Three Kings, and The Usual Suspects. Along with those films, Sigel has been a key contributor as Director of Photography on a majority of the X-Men franchise with X-Men, X2: X-Men United, X-Men: Days of Future Past, and X-Men: Apocalypse.

Sigel holds more than 35 nominations from prestigious awards and festivals in cinematography on numerous films. The cinematographer has won a total of five awards from multiple industry critics groups and festivals, including the Visual Effects Society (VES) for X-Men: Days of Future Past, Utah Film Critics Association Awards for Drive, Sundance Film Festival for When the Mountains Tremble, and his work in The Big Empty in the Malibu and the USA Film Festival.

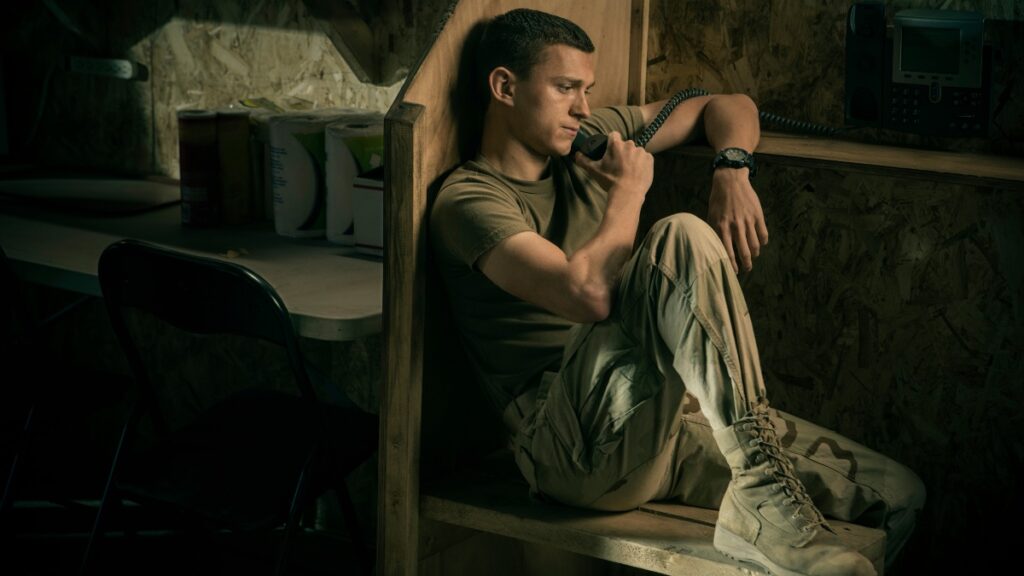

Sigel’s latest film, Cherry, is a collaboration with the highly-touted directors Anthony and Joe Russo (Avengers: Infinity War, Avengers: Endgame), based on the novel from Nico Walker with a screenplay written by Angela Russo–Otstot and Jessica Goldberg. The adaptation, being released by Apple TV+, begins with Cherry (Tom Holland), a young wide-eyed college student in Ohio as he is suddenly swept away by the love of his life Emily (Ciara Bravo). Soon after, Cherry enlists in the army. After his return, he suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), becomes dependent on drugs, and turns to bank robbing for his opioid addiction and debt from the drugs. The cinematographer beautifully shot the movie in six distinct chapters: Part One: “When Life Was Beginning I Saw You,” Part Two: “Basic,” Part Three: “Cherry,” Part Four: “Home,” Part Five: “Dope Life,” and Part Six: “Epilogue.” (Spoilers ahead!)

The visual design for Cherry originates from the book. Sigel explained, “The look for Cherry came out of a conversation with Joe and Anthony Russo. The origins of everything, the story, the aesthetic, and the way to approach the film began with the book. In the book, it was written in a unique and individual voice that had a lot of influence in the way that the screenplay was written. Built into that screenplay was this very subjective, ironic, breaking the fourth wall, somewhat slightly absurdist, and always poignant voiceover that addressed the camera. It was very much done in chapters. As we follow this character from a very innocent, young smitten college student to Iraq and war, and returning with PTSD; eventually, drug addiction and criminality. We told those phases in the story with different chapters that each had their own defining characteristics and look, the stage in his life, and where he was going. We have visual references, images that we would share back and forth, some looking at film, a lot of discussion sitting and talking about what the intent of any given section was, and then throwing out ideas about how we could express that. Joe and Anthony were very eager to encourage bold solutions and more out of the box, risky methodologies for getting these ideas and emotions across. That’s basically how it came to be as exotic a film as it ultimately is.”

The cinematography melds and transforms in each distinct chapter. “The bulk of the beginning part of the film is really the story of a young college kid falling in love and the deployable of that. It’s like a fairy tale. It was shot with very old anamorphic lenses that have a very romantic and unusual look with the out of focus areas of the frame that get very painterly and swirly. It’s just a very fairy tale feel to it. Through bad luck and a bad decision, he joins the army and goes to basic training. All of a sudden, he’s gotten himself boxed in where he didn’t want to be and the shape of the frame changes. It goes less widescreen to a square frame. Their lenses change to extremely wide angle, flat spherical lens that has a clean, crisp look, but a lot of distortion. The color becomes much colder than the warmer more inviting tones of his early idealistic phase. Then he’s off to war. He goes to war and this screen opens up again. It becomes this naïve young American’s first experience with the world at large and the horrors of war. For that, there’s a lot more vibrancy, color, and the lens choice is really a variation on the classic photojournalist lenses. Then he returns home and we come back to the look where we started, except he’s a very different and broken man. The frames become all of a sudden off balance, asymmetrical, and uncomfortable compositions. The color becomes increasingly drained, the images become darker and more shadowy; until finally he winds up in prison. In prison, we have a very stark, clean, unflinching, yet removed look. The final sequence or the epilogue is done with a very specific camera movement that carries us up to a moment of epiphany when he’s made a choice of, I’m actually going to try to make something of my life and his desire to create a life. We conclude with his exit from 11 years in prison to the potential of what is yet to come,” the cinematographer described.

The color palette evolves and shifts tones within the major parts to accentuate the visual representation. The director of photography expressed, “In the beginning when he first sees Emily and falls in love, they have this funny relationship and we have a lot of warm tones. It’s a very rich palette, but period like almost slightly 60s or 70s quality color, a little bit of a Kodachrome feel. Then the minute we hit basic training, all that warmth goes away and the color is at best neutral if not cold, so the blues are predominantly much stronger. Then we hit Iraq and the colors of the desert start to take over and we get a lot more sand and tobacco quality colors. When we come back to Cleveland, they start to go away. As the descent into drugs accelerates, we find the location not only darker, but the colors themselves start to lose their vibrancy as their life gets drained away. We still have color but it’s becoming swallowed up by the shadows. Then we wind up in prison. Prison is neutral, very down the middle; until the very end when he’s let out on parole and a little bit of warmth starts to come back into his life.”

A variety of framing, angles, shots, movements, camera techniques, and lighting methods are applied throughout. “The beginning of the film has more of a lyrical look from a compositional point of view as it became more unbalanced and disturbing when he returned to Cleveland after Iraq. Iraq itself had a lot more handheld and a journalistic feel to the photography, except maybe when we’re at the base where he was amongst his peers with an absurdist feeling. It really heightened when he was in basic training. It was all done on this very wide 14-millimeter lens when the subject’s very close to the lens and there’s a lot of distortion. The frame was 1.66:1 frame as opposed to a 2.39:1 frame, which means less widescreen and more squarish. There’s a thought in the car where we first introduce all of Cherry’s friends, which are really his community and define a little bit about who he is. It’s all done from his point of view inside a car where we see his friend driving, stopping, and picking up two of the other friends and then the camera finally comes around from his point of view into Cherry’s face in one shot inside the car. It’s a way of establishing his community, his posse. There’s a beautiful transition early on where we have a tease of what will ultimately become Cherry’s final bank robbery where he goes into the bank and points a gun at the teller. We have this internal suspended moment where we go into his thoughts and it’s about the fact that in another world and life, he could have formed a life or been in love with this young lady that’s a teller, but now he’s here pointing a gun at her. We go into that transition by taking all of the beautiful light that’s streaming through the windows, light in the background and the atmosphere, and all the other customers, moving it off the environment; so that everything becomes dark, except for Cherry and this young bank teller. That transitions to the reverse of that where we see Emily in a school classroom and she’s this beautiful young lady lit like she’s out of some 40s glamour movie. The rest of the classroom is dark, we can barely see any of the other students, the light is moving through the window, Cherry is completely transfixed, and then the world comes back to normal and the light comes on and we start to see all the other students, and we realize we’re just in a regular old classroom. That was a way we used a lighting technique to take us into the psychology and back out of the objective world as a way of starting with his tease and going back to the beginning where he first saw what would be his love,” Sigel detailed.

The drug scenes are shot to represent an altered state and disorientation. The cinematographer enlightened, “Early in the film, we established that he has anxiety issues and takes Xanax to cope which makes him vulnerable. When he returns from Iraq, he’s unable to acclimate back home, so he gets offered opioids by his VA doctor. That starts to take him in a different direction. Initially, Emily his love, waited for him the whole time when he’s in Iraq and is resistant and annoyed. Then she turns a corner when she just can’t take it anymore, caves, and becomes equally addicted. Before that moment, one of the inciting incidents is when he comes back home, he’s completely messed up, and she’s throws a fit. We showed that by building a little rig that Tom Holland was standing on that we could push him around where he didn’t have to actually walk, but it looked like he was floating through the room. It allowed him to sway from the waist from side to side or backward and forward; it enhanced this floating feeling of being completely disoriented. Then the camera was mounted to the same rig, so they moved together, yet he moved independently of the camera in the sense that he could move around the frame, not just locked into the camera. We took it to another level by adding a huge piece of glass in front of the lens that distorted the image, the edges, and the color. It brought that distortion out even further by lighting through the windows of the bedroom to the point where they’re blown out, very overexposed, and glowing. The whole package created this feeling of complete altered state, disorientation that he was going through.”

“One of the challenging aspects when we deal with things like PTSD or with the opioid crisis is how to make people understand how horrifically damaging these pandemics are and yet how we have to have some feeling of possibility or potential of hope or there’s just no point in carrying on. One of the biggest challenges is finding a way to relate to the audience that horrific, destructive aspects without making an audience feel completely hopeless and miserable.”

Cherry exemplifies beautiful cinematography embodied within distinct chapters. The cinematography visually depicts Tom Holland’s deep transformation from an innocent college student to a military veteran suffering from PTSD, a drug addict, a bank robber, and then with the hope of a fresh start. The film utilizes a variety of cinematography techniques from the lighting, lenses, framing, angles, movement, and color to differentiate the significant phases of Cherry’s life.

Cherry is now playing in select theaters and will stream on Apple TV+ on March 12.

Photos courtesy of Apple.