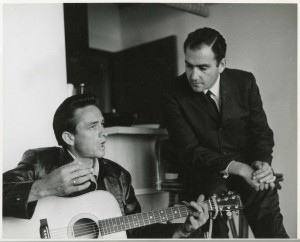

Consider the recent unprecedented case of 48 year-old, Canadian resident, Jonathan Holiff. This former agent entered the documentary film forum when he came across previously ignored media concerning the singer Johnny Cash through the prism of Cash’s personal manager, Holiff’s recently deceased father Saul Holiff. Jonathan approached this film, My Father and the Man in Black, in a series of recreations, animations, motion graphics, stock footage and pieces of actual audio and film footage he only discovered after his father’s passing.

“I stumbled upon a complete record of these two men’s lives on audio in their own words,” he said. “There was no reason to do talking heads. I already had the whole story in Johnny and Saul’s own words. I decided to do something risky. Most purists have an aversion to recreations. These are not dialogue recreations. They are all from the historical record, discussing exactly what was going on.”

Through the course of the film, previously unknown information is revealed about Cash. And through the course of filming it, otherwise unknown facts about the filmmaker’s father were revealed. Being a novice filmmaker, Holiff approached his subject tactfully and decided to shoot everything on 35mm film.

With purpose, Holiff strategized to bring a steady flow of visual information to the audience. “My disposition is more like younger people today,” Holiff said. “The Smartphone generation wants its information coming at them at light speed. I tried to make the pace of this story move quickly and mixing and matching different forms of artistic expression. I mixed live action with 50-year-old photographs, working hard to make sure that the live action fit into the scheme of things.”

Holiff also introduced himself as a character in the story, explaining in first-person how and why he put together this untold story of Cash and his father. “First-person documentaries are very rare,” he said. “If the audience doesn’t like you in the first 10 minutes, you’re dead. It was an unparalleled opportunity for me to reconcile with my father — to get to know my father and know what he truly felt inside; he seemed preoccupied with business and family.”

Holiff had initial doubts about the project, but he eventually realized the revelation of his father’s personal collection of media about Cash warranted a film. “I had never written a short story or was an artist in any way, shape or form,” Holiff confessed. “My mother suggested I write a book. I thought it might make a good one-hour Canadian doc. I wrote a treatment and sent it to my friend. He said, ‘Jonathan, this is a movie and you should tell it from your point-of-view.’ It was a very cathartic experience. I got this gift for my father that was not necessarily intended, but was well-received.”

Holiff likes the idea of his father witnessing the completion of this film from above. “I think he would get a big kick out of it,” Holiff stated. “Narcissists keep records of their entire lives. He also enjoyed the fame and the status that he enjoyed being Cash’s manager. He would be tickled pink to have a movie made about him.”