Every Oct. 31, children fill the streets in masks and costumes, their parents cavort at parties in similar attire, and others remain at home watching the works which inspired Halloween’s evergreen icons: the Universal Classic Monsters. A testament to the care with which these films were conceived and realized, Halloween’s yearly staples include phantoms, vampires, werewolves, mummies and monsters, all of which could be traced back to the original black-and-white pioneering films of the 1920s-1950s. And just as surely, the notable characters were brought to life by a staple of unprecedented below-the-line talent working at Universal in different eras of studio ownership.

Every Oct. 31, children fill the streets in masks and costumes, their parents cavort at parties in similar attire, and others remain at home watching the works which inspired Halloween’s evergreen icons: the Universal Classic Monsters. A testament to the care with which these films were conceived and realized, Halloween’s yearly staples include phantoms, vampires, werewolves, mummies and monsters, all of which could be traced back to the original black-and-white pioneering films of the 1920s-1950s. And just as surely, the notable characters were brought to life by a staple of unprecedented below-the-line talent working at Universal in different eras of studio ownership.

Depending on one’s definition, the Universal classics span 1931-1945 but could also include films beginning in 1925 and running to 1956. In point, Universal produced the first lavish cinematic production of Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera in 1925, starring Lon Chaney, Sr. in a ghoulish makeup of his own design that has remained the most recognized of Phantom characters amongst the many which have come since. Using primitive techniques and materials, and without the benefit of sound, Chaney’s character, first unmasked in a landmark cinema moment, scared audiences to new heights at the time with his high cheekbones, upturned nose, and skeletal visage, and has yet to be topped in terms of its immediate recognizability.

Universal’s next major project in the genre was Bram Stoker’s Dracula, rumored at the time to be designated for Chaney to star in (though he died before production) since the film’s director was Chaney’s friend and frequent collaborator Tod Browning. Alas, eventually cast with Béla Lugosi, Dracula became an international sensation and ushered in a genre not only at Universal, but also at nearly every major studio at the time. Lugosi’s gestures, expressions, mannerisms, costume and vocal stylings remain to date the definitive Count Dracula and are referenced in numerous imitations, to say nothing of the equally countless manifestations in films, television shows, TV commercials, and a mass of Halloween materials. Due credit must also be paid to cinematographer Karl Freund who maximized the eerie potential of Dracula’s gothic expressionistic sets, created by art director Charles Hall.

Universal’s next major project in the genre was Bram Stoker’s Dracula, rumored at the time to be designated for Chaney to star in (though he died before production) since the film’s director was Chaney’s friend and frequent collaborator Tod Browning. Alas, eventually cast with Béla Lugosi, Dracula became an international sensation and ushered in a genre not only at Universal, but also at nearly every major studio at the time. Lugosi’s gestures, expressions, mannerisms, costume and vocal stylings remain to date the definitive Count Dracula and are referenced in numerous imitations, to say nothing of the equally countless manifestations in films, television shows, TV commercials, and a mass of Halloween materials. Due credit must also be paid to cinematographer Karl Freund who maximized the eerie potential of Dracula’s gothic expressionistic sets, created by art director Charles Hall.

That same year, a Halloween home-run followed Dracula with Universal’s Frankenstein, based on the Mary Shelley novel, featuring the equally immeasurable success of Boris Karloff as the monster. Not only was Karloff’s performance remarkable in every sense, the film surpassed Dracula in terms of production design, realized to perfection with laboratory sets and designs by Hall, sumptuous cinematography by Arthur Edeson, groundbreaking costumes by Vera West, vivid photographic effects by John Fulton, and revolutionary makeup by Jack Pierce. This team, who would work on additional films during the 1912-1936 Carl Laemmle era at Universal and beyond, set new standards for every phase of the Frankenstein production.

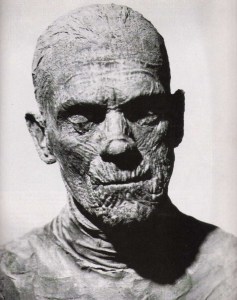

In 1932 and 1933, Universal created an original film, The Mummy, and a filmed adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man, respectively, extending 1931’s triumphs and providing ample opportunity for the studio’s mainstay craftspeople to shine. Freund stepped into the director’s chair for The Mummy, which again featured Karloff in a Jack Pierce makeup of painstaking specificity. Only seen onscreen for a few moments, the full Im-Ho-Tep mummy, 82 years onward, is still the mummy emulated in many homages and representations which have followed. West and Pierce amazingly went uncredited though Fulton and cinematographer Charles Stumar were acknowledged onscreen for their significant contributions. Fulton’s effects in The Invisible Man, outstanding for their time, provided additional thrills, though his masterwork was still to come.

In 1932 and 1933, Universal created an original film, The Mummy, and a filmed adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man, respectively, extending 1931’s triumphs and providing ample opportunity for the studio’s mainstay craftspeople to shine. Freund stepped into the director’s chair for The Mummy, which again featured Karloff in a Jack Pierce makeup of painstaking specificity. Only seen onscreen for a few moments, the full Im-Ho-Tep mummy, 82 years onward, is still the mummy emulated in many homages and representations which have followed. West and Pierce amazingly went uncredited though Fulton and cinematographer Charles Stumar were acknowledged onscreen for their significant contributions. Fulton’s effects in The Invisible Man, outstanding for their time, provided additional thrills, though his masterwork was still to come.

Many studio stalwarts’ techniques coalesced with Whale’s The Bride of Frankenstein in 1935. Often called the greatest of the films by keen observers, Bride featured a redesigned makeup for Karloff’s monster which Pierce revised from his first 1931 version. Hall again designed magnetic sets while West, in concert with Pierce, presented a titular Bride character using actress Elsa Lanchester who also appears in a small role at the outset of the film. Only seen onscreen for the films final climatic minutes, the Bride is regularly counted among the top slate of Universal monsters. Presiding over the refined look of Bride, which was perhaps given more studio care than the first film, John Mescall’s winning cinematography might be among the best ever realized for a horror film.

Unfortunately for the father-and-son Laemmles – Senior was president of the overall studio while Junior oversaw production – Universal fell on hard times in 1936 and the reins changed hands the next year. Not only were the Laemmles out, but James Whale had left by that point as well. Soon afterwards, a conflagration of events found the new regime interested in another Frankenstein sequel, leading to Son of Frankenstein, released 75 years ago. In addition to Pierce and West’s typically formidable work, Son’s true high mark is one of art direction, for this outing, created by Jack Otterson who replaced Hall on many of the films. Otterson’s sets are an otherworldly expression of pure creativity with its bizarre exaggerated hallways, furnishings, window dressings, underground laboratory and other accoutrements. Karloff and Lugosi, who teamed for several mid-1930s studio pairings, co-starred in the third Frankenstein film, closing out horror’s most magical decade of all time.

Unfortunately for the father-and-son Laemmles – Senior was president of the overall studio while Junior oversaw production – Universal fell on hard times in 1936 and the reins changed hands the next year. Not only were the Laemmles out, but James Whale had left by that point as well. Soon afterwards, a conflagration of events found the new regime interested in another Frankenstein sequel, leading to Son of Frankenstein, released 75 years ago. In addition to Pierce and West’s typically formidable work, Son’s true high mark is one of art direction, for this outing, created by Jack Otterson who replaced Hall on many of the films. Otterson’s sets are an otherworldly expression of pure creativity with its bizarre exaggerated hallways, furnishings, window dressings, underground laboratory and other accoutrements. Karloff and Lugosi, who teamed for several mid-1930s studio pairings, co-starred in the third Frankenstein film, closing out horror’s most magical decade of all time.

At Universal, Pierce, West, and Fulton survived into the 1940s when many Frankenstein, Invisible Man and Mummy sequels dominated the studio’s genre output. However, one unexpected surprise arose in 1941. Based on Curt Siodmak’s original screenplay, The Wolf Man might not have been the first werewolf film – the studio had released Werewolf of London with Henry Hull starring in the title role in 1935 – but it was eventually known as the studio’s best such film. Moreover, the title character, played by Lon Chaney, Jr., would become as instantly renowned an undeniable horror character as Lugosi’s Dracula, Karloff’s Monster, or Lanchester’s Bride. Directed by George Waggner, in The Wolf Man, Pierce and Fulton, working with cinematographer Joseph Valentine, would collaborate to bring forth the “transformation” of a man into a wolf and back again, a scene which would resurface in a slew of Wolf Man film appearances in the 1940s. Using Fulton’s lap dissolves, Pierce’s meticulous lycanthrope makeup would be reverse engineered for the wolf-to-man scene in the film’s climax. Of the many werewolves which have come since, few have matched – and none have replaced – the 1941 Wolf Man as the ultimate version of the character celebrated in popular Western culture.

After a series of “monster rallies” which combined many of the characters in various sequels, Universal stopped producing what is now known as the most classic of horror films. Aside from a comic take in 1948’s Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, the studio moved onto other types of films in the postwar era; sadly, Fulton, West and Pierce were all dismissed following a 1947 merger with International Pictures. In one sense, the 1931-1945 cycle was over, but a wholly new type of character would rise from the depths in 1954 with The Creature From the Black Lagoon. Directed by Jack Arnold, the film presented a title character unlike any seen on screen to that point. Part-man and part-fish, the Gill-Man, supervised by Bud Westmore and a large team of makeup department technicians, was deserving of its placement alongside Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy, The Bride and the Wolf Man in its impact and unforgettable status in the horror genre. Played by Ben Chapman for land sequences and Ricou Browning in swimming sequences, the Gill-Man was unlike any monster before or since his appearance and played in two sequels, stretching the classic monster period in another sense to 1956.

After a series of “monster rallies” which combined many of the characters in various sequels, Universal stopped producing what is now known as the most classic of horror films. Aside from a comic take in 1948’s Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, the studio moved onto other types of films in the postwar era; sadly, Fulton, West and Pierce were all dismissed following a 1947 merger with International Pictures. In one sense, the 1931-1945 cycle was over, but a wholly new type of character would rise from the depths in 1954 with The Creature From the Black Lagoon. Directed by Jack Arnold, the film presented a title character unlike any seen on screen to that point. Part-man and part-fish, the Gill-Man, supervised by Bud Westmore and a large team of makeup department technicians, was deserving of its placement alongside Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy, The Bride and the Wolf Man in its impact and unforgettable status in the horror genre. Played by Ben Chapman for land sequences and Ricou Browning in swimming sequences, the Gill-Man was unlike any monster before or since his appearance and played in two sequels, stretching the classic monster period in another sense to 1956.

In their many incarnations as physical masks and costumes, and in all manners of public media, the Universal Classic Monsters have lived on for nearly a century and have transcended the many generations of fans and followers who have paid tribute to them in dozens of Halloweens since they first graced screens.

In their many incarnations as physical masks and costumes, and in all manners of public media, the Universal Classic Monsters have lived on for nearly a century and have transcended the many generations of fans and followers who have paid tribute to them in dozens of Halloweens since they first graced screens.