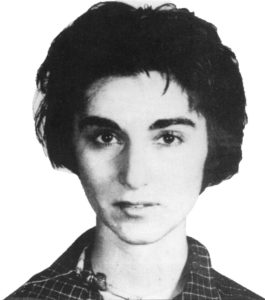

Studied in collegiate psychology courses for the past 50 years, the murder of Kitty Genovese on March 13, 1964 in her adopted hometown of Kew Gardens, Queens, New York City became emblematic of 20th century apathy and the cold impersonality within America’s decaying urban environs. Two weeks after the crime, The New York Times reported that the murder had been witnessed by over three dozen residents in the neighborhood and that no one had tried to help or even call the police. At one point, The Times stated, the killer was scared off, but he soon returned to finish what he had started. The article sent shockwaves throughout the United States and beyond, and the murder has since been designated as one of the most avoidable of all capital crimes from modern history.

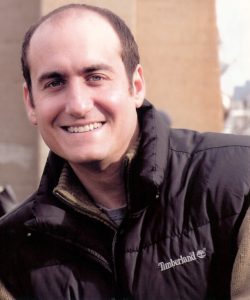

However, a new documentary, The Witness, directed by James D. Solomon, unearths new interviews and facts and thereby debunks one of America’s most reported and impactful crimes and urban myths. In many respects, it also explores the power and consequences of flawed journalism in very personal terms. In the course of the film, told through an 11-year personal investigation into the events of March 13, 1964 by Kitty’s brother, Bill Genovese, The Witness reveals just how much of an impact a compromised story has on the lives of so many, not only in the Genovese family, but also the many residents of Kew Gardens and even the family of Kitty’s murderer.

“What drew me to make this film,” said Solomon, “was the lives affected by both Kitty’s death and her life. It’s also a sibling love story. The surprising thing is that for the general public, Kitty was not known as someone other than the last 32 minutes of her life. The same occurred in Kitty’s own family. The horror and public aspect of her death erased her life even within her own family.”

For Solomon, The Witness, his first feature as director, served as an entry point into one of New York’s most reprehensible moments in the eyes of the public. “I didn’t realize quite at the time just how much the narrative of New York was set in motion by the Kitty Genovese story,” said Solomon, who first considered writing a narrative screenplay of Kitty’s life and death. But then he met Bill Genovese and realized that there had already been a wealthy of fictionalizations of the story. “For decades,” he added, “everyone from journalists to academics to dramatists had been telling this story, but the people most affected had not been heard from. There needed to be a non-fiction project to document those who actually lived it.”

Starting in 2004, Solomon followed Bill Genovese’s investigation into the people and places crucial to his sister’s life and tragic end. “That led down so many roads that we never could have imagined,” said Solomon. “How the story came to be, who his sister was, and also who Kitty’s killer was. As [Bill] unraveled and chased these mysteries, ultimately, he was chasing the mystery of some unanswerable questions of life dealing with the tragedy of the loss.”

Throughout The Witness, Solomon encounters many neighbors and their family members who tell a story tangential to the textbook version of Kitty Genovese’s death with many startling additions and omissions. “You often learn more about a witness from what they see or hear than what actually happened,” Solomon related. “The film not only explores the false narratives or flawed narratives that people told in the Kitty Genovese murder, but also what people saw or heard in the middle of the night. Stories we tell are shaped by time. Bill Genovese is… a man who is determined to seek the truth and take on the powerful institutions that make the city run. Bill Genovese is the most remarkable character who I’ve ever had the opportunity to portray. His relentless determination and devotion to his sister is extraordinary.”

Indeed, The Witness comes across as one man’s personal journey in equal stead with the subject matter he is exploring. We hear Bill Genovese’s running voiceover as he encounters city officials, Kew Gardens’ residents, and others attached to the March 13, 1964 events. “It was critical to me that the audience feel as close to Bill’s investigation as possible,” Solomon conveyed. “I wanted to take myself out of the equation and allow Bill to drive the narrative. To do that meant hearing directly from Bill. Most first-person films, the filmmaker is the narrator of the film, the driving force. I was a filmmaker documenting Bill’s investigation — I interviewed Bill over the course of 11 years frequently. From that, the narration was drawn.”

As Solomon believed that many in the film would not have spoken to anyone other than Bill Genovese, following him in the film was a natural gateway to discovering and re-examining Kitty Genovese’s story. As such, Solomon had unprecedented access to the story, unlike anyone in media since the late winter of 1964. “They felt they owed it to Kitty,” Solomon noted of those who appear on camera. “They were willing to speak to Bill Genovese. He has this way of making people feel comfortable. So many in the film who similarly are holding onto stories [of] pain and their own loss are willing to open up to Bill.”

Aside from interviews, animations, and Genovese’s narration, Solomon presents a visceral re-creation of the circumstances surrounding the March 13, 1964 night in question. “Bill wanted to do that,” Solomon explained. “It was on his mind for a long time. He had been returning to that scene on Austin Street [in Kew Gardens] for many years over the course of his investigation. It was always not far from his mind imagining what happened that night. Bill has wondered about it for a half-century.”

In the recreation, an actress, Shannon Beeby, plays Kitty Genovese in the exact locations where she was killed. “The neighborhood would not have allowed anyone other than Bill to do that,” said Solomon. “We filmed in the early evening hours. He thought it was going to be more of an aural experience – to hear what it was like. He didn’t realize how cathartic an experience it would be. He was constantly wondering what it was like that night. That location is exactly the same — except for the signage, nothing has changed. You see how it unfolded; you are going back to that moment. It takes your breath away. It’s horrifying.”

Without question, the Genovese family was immediately transformed by the final 35 minutes of Kitty’s life 50 years ago, but when Solomon’s film was complete, after an 11-year odyssey, he realized that the murder had a serious impact on many lives. “Not just the Genoveses but the lives of the witnesses, [convicted murderer] Winston Moseley’s family, and the city,” he said. “Both what actually happened and what was reported to have happened in that moment. What’s essential is that you have the kind of feeling that you have for Bill, borne of having lived with him as a viewer. You have been invested in this extraordinary person. I could not have made a film just about Kitty Genovese. I made a film about Kitty through Bill. We are fully invested in Bill: the effect that her life and her death had on his life.”

The Witness is now on Netflix, iTunes, and Amazon and will appear on “Independent Lens” via PBS in January, 2017.

For more information, go to www.kittygenovesefilm.com.