Composers and musicians Ben Salisbury and Geoff Barrow have scored all of filmmaker Alex Garland‘s work to date, including three features and the FX series Devs, but their score for Garland’s summer release Men is next-level — it’s music that’s as haunting and eerie as the film itself.

For those unfamiliar, Barrow is one-third of the acclaimed British band Portishead, while Salisbury comes from a background scoring nature films and such. Their work together has been quite fantastic so far, to the point where the soundtracks to Garland’s heady films have been nearly as popular as the movies themselves.

Men stars Jessie Buckley as Harper, a woman whose husband has recently died, so to get away from everything, she rents a remote house in a small community, where she quickly begins to experience strange things — in particular, the behavior of the local men, most of whom are played by a mischievous Rory Kinnear.

A few months ago, Below the Line spoke with Salisbury, who discussed his collaborative process with Barrow, as well as how the two of them have worked with Garland over the years. He also talked about Buckley’s own contributions to the soundtrack of Men and its unique use of birdsong.

[Note: Men has been out for many months, so there may be a few spoilers in the interview below.]

Below the Line: I saw that you have extensive experience scoring nature docs before you started working with Geoff Barrow. When did you meet him and start working with him to compose music?

Alex Salisbury: I had a fairly, sort of, standard-ish TV composer background. [I was] living and working in Bristol, which is the home of Natural History Documentaries worldwide. All the David Attenborough stuff is made here. That was the funnel for most people wanting to get into composing. I had quite a long time — 10, or maybe more years doing that — and had done David Attenborough — Life of Mammals, Life in the Undergrowth — so those big “blue-chip” [projects] as they’re called, and they’re great. I’d never ever knock them, but they really require one sort of music, especially the blue-chip ones, and there’s very little, other than beautiful aerials, chase scenes — which is not to knock them, [because] they have some amazing opportunities for music, but I didn’t really get into writing, doing composition, to do that sort of thing.

I’d always wanted to do dramas, and I found it was very hard to cross over, that you can get pigeonholed very easily — I was the nature guy. As hard as I tried, I had that catch-22 situation. I met Geoff about 15 years ago now, maybe more weirdly, through playing football — or soccer as you call it — on a really rubbish old man’s Monday night kick-around thing, [which] we still do. When I first met him, I obviously knew of Portishead. They had been one of my favorite bands, but weirdly, [and] I don’t know why, [but] Geoff wasn’t the face that I knew of Portishead. Actually, Adrian [Utley, another member of Portishead] lived near me, so I vaguely knew him — didn’t know him, but knew his face. I hadn’t put two and two together.

[I was] playing football for three or four years with this guy, Geoff, before it dawned on me, or someone told me. I needed some musicians for something, a conga play or something, and the guy I was playing with, who I did know, I said, ‘Do you know any conga players?’ And he said, ‘Why don’t you ask Geoff?’ And I said, ‘Why would Geoff know?’ And he said, ‘Well, that’s Geoff from Portishead.’

Then, we got chatting about music, and I needed some advice on sample clearance, actually, from a mate’s album that I was helping him out on. I also then played Geoff some of my natural history stuff. I knew it wouldn’t be the stuff that Geoff was massively into, but I knew what he did musically — he didn’t know I did — and he was like, ‘Oh, yeah, I get that, and I really need [some] string arrangements done for some bands on my label.”‘So I did some string arrangements for a guy called Joe Volk, and worked on his album with him. I was wanting to get into dramas, and Geoff was wanting to get into film music as well, so we both just said, ‘Look, if the opportunity comes up, why don’t we try doing something together?’

The opportunity first came up with Alex Garland, actually, on the Dredd film, where he was put in touch with Geoff through a mutual contact because he knew that Geoff was a fan of Judge Dredd. And Geoff said, “Yeah, I’d be interested in that, but can I do it with Ben?’ And Alex said, ‘Yeah, great.’ And so, we started doing work on the Dredd film.

I think the story is quite well-documented how we started on it, but it didn’t last the course, because we were doing sort of an arthouse score. At a certain point, the studio decided a lot of things had to change with the film, one of them being the score. We had the opportunity to change it, but there was no way of changing the approach we’d taken without it becoming rubbish. It was best for all concerned that we sort of stepped away, but we kept the music that we’d written and we released it. I can understand why they had problems with it, but we loved it. We released it as an album, it was quite a niche thing, but Alex loved it as well.

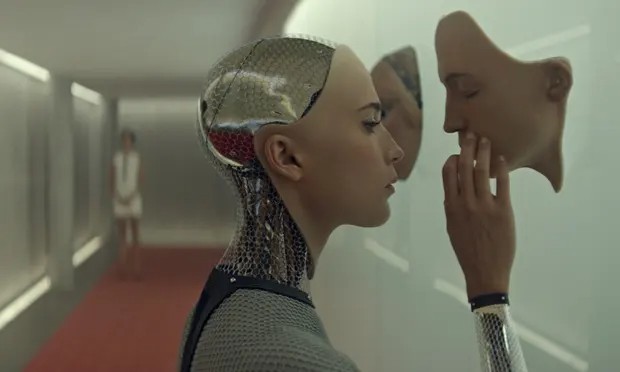

He just said, ‘Next time, if I’m more in charge of a film’ — which he was, with Ex Machina — he said, ‘Come on board early on, and we’ll make you sort of irreplaceable if we can. Do the temp score, even,’ so we did, and that was the start of our relationship with Alex Garland. That was the start of mine and Geoff’s collaborative process as well, so Ex Machina holds a special place for all of us.

BTL: Having worked with Alex for so long, when he comes to you with something like Men, when does he come to you and say, “I’m doing this movie.”

Salisbury: Good or bad, Ex Machina set the template, really. That was a creative success for us all around, we felt, and so, it really set a template for the way [that] me and Geoff work with Alex, which is, come on board very early, and that has massive benefits. So we always get the script. We didn’t for the one he’s shooting at the moment [Civil War] because he shot it all in the States, but for every other one, we’ve come to a couple days of the shoot as well, to get an idea of it. We’ve talked to the actors.

For Annihilation and Devs, I walked around the pre-production, where they were building sets, so you really get a chance to feel like you’re part of the film. You’re not just this bolted-on bit at the end. I’m doing demos at the moment for his next one even though I haven’t seen anything; they might well completely change [everything], or they might hit the nail on the head. We start [early] so that we get over this problem, which is standard in the film industry, as you probably know, of grabbing stuff off the shelf, music from someone else, which sometimes becomes incredibly difficult to replace.

The downside of that is that you often end up writing the score five times over because the film constantly evolves and changes. Ex Machina is a good example. We wrote an infatuation theme between Caleb and Ava, and we placed it in the first time he sees her on CCTV, and then, it sort of grew from there, and we all got two-thirds of the way through the film before Alex realized, ‘Wait there, he’s falling in love with her too early. She’s a robot, after all. We’re going to have to change that first cue.’ We haven’t got many other tools that are within our grasp, so we changed that first cue. That then had an effect on the next one, and the next one. All these pillars that we had built crumbled, and we had to do the whole thing again.

We get on early, but it does mean that we’re right there. We’re seeing the edit develop, we’re seeing the CGI come in. We’re involved before the sound most times, so we have an influence there. We way overstep our brief as composers by having opinions on cuts, and the way things are developing, which is amazing. It is a very collaborative process. It means it takes longer than normal, so you can’t do as much work in a year as other composers tend to. When we’re tied up with an Alex thing, we are tied up with it, but I wouldn’t change it really.

Men was, actually, in some ways, the smoothest and the shortest, but we knew the time period was condensed that we had to compose it. The thing that we’ve normally done is hand over initial ideas, and they’ve gone through a massive washing machine of process and come out the other side and [they] change or get abandoned. On this one, we knew that it was important that we sort of nailed it early on, and we did. That’s partly because it’s one of his most weirdly straightforward scripts. It was very easy to grasp. I know [there are] lots of reviews and lots of talk about it being very oblique. I personally didn’t find it that way with the script. It was very clear-cut how the music should work. I had this idea. I mentioned it to Alex. He said, ‘Yeah, that sounds great. Give me a demo of it, so I understand what you’re talking about,’ which was essentially this idea of using a countertenor as the main voice. It was all during [the] lockdown, so I got the countertenor to sing these parts over a Zoom call with him in a studio in London. Those demos almost became the score. We got a first cut of the film back and it had mine and Geoff’s demos all over it. I think all of us would have walked away happy and said, “That works as it is.” We then had the normal back and forth, and we managed to invent ways of making it harder for ourselves, but it really did work well, actually, on this one.

BTL: The score is really eerie and haunting. When I listen to it separately from the visuals, it still evokes the same emotion and feelings as when I saw the movie. I’m curious just how knowledgeable Alex is about music. Does he know anything about major vs. minor chords or things like that?

Salisbury: Much to our dismay, he’s getting more and more knowledgeable. By his own admission, he’s not a musical person, in terms of, [he] hasn’t studied or learned any instruments, but he’s desperate to understand everything. Anyone who’s watched any of his films [knows that] music is such an important part of his filmmaking process. That’s why it’s so great to work with him, and it’s such a creative rollercoaster ride of ups and downs — because it is a massively important part of his filmmaking process. There’s not a single film we’ve worked on [that] hasn’t had a 10-minute sequence of just visuals and music. He always manages to get that in — Annihilation, he did it; Ex Machina, he did it; Devs, those sorts of sequences were all over the place. [That’s] sort of a dream for a composer. He totally knows what he wants to get out of the music and its relationship to film, and he’s worryingly getting more and more adept at knowing terms and phrases. “Why don’t we just put this down an octave?” [and] all of that sort of stuff, which is great. He soaks it up and wants to know exactly what’s going on. When we make that change, and it suddenly works, it’s like, ‘Why did that not work, and why does that work now? I know what works in terms of picture and what is making me feel, but what have you technically done?’ It’s a brilliant mix of a massively collaborative process with Alex. He’s the first to admit it.

He never ever puts “A Film by Alex Garland” — he finds that way of naming films almost offensive. It’s a film written and directed by Alex Garland, but he always calls it “our film.” It’s our film that we all are involved in, but in saying that, he’s got his hands over every single aspect of it, and I’m sure he’d love to write the music himself one of these days, but unfortunately can’t, so he’s gotta rely on us West Country bumpkins to help him out.

BTL: That might be partially to blame on film critics, because we tend to use that shorthand of saying, “It’s a David Cronenberg film,” or “Alex Garland’s latest film”…

Salisbury: I think that’s completely fair enough, really. You take a step back from it, and it is, totally, an Alex Garland film. Anyone who watches or is versed in the aspects of filmmaking, who watches a lot of films, would know an Alex Garland film, as soon as they saw it. I think he probably hates this word, but he is an auteur, really, and they’re great people to work with. To have someone who brings other people with him, he really does take on board stuff that we bring to the table, but ultimately, he is the guiding force in it. They’re properly special things to be involved in, though.

BTL: You mentioned going to the set of Annihilation and Devs. Obviously, Men was made during a pandemic, and part of the nature of that film being easier to make was just having Jessie and Rory and Alex and a few others on set. Were you still able to go to the set at all?

Salisbury: Towards the very end, during one of the tiers of lockdown restrictions, they still had a couple of weeks left on the shoot, and a certain element of the lockdown restrictions had lifted. There were protocols of mask-wearing and test-taking and all that, but we were able to go to set one day; it was shot very near to us, actually. It was an hour up the motorway from where Geoff and I live, all contained in this little village in the Cotswolds, and it was a fascinating shoot to go and see. We actually saw the final day of the night shoot, which they’d run out of time to do at night, so they blacked out all the windows of the house and were doing the final section. I think Alex shoots more or less chronologically, so it was the final you see of that night shoot, so the culmination of that third act.

We walked into this beautiful Cotswold village and this amazing idyllic country house, and in the garden, there were the remnants of what they’d been shooting over the last two weeks, which included prosthetic bodies lying around. I don’t want to give any spoilers, but for anyone who’s seen the film, there was a lot of CGI in there, but they also used this mix of prosthetics, so all those bits were lying around the front garden of this house. We watched a bit of that. Obviously, from reading the script, we knew how insane it got at the end.

Although I know that part of the world really well, just being there and absorbing the place, there’s one little aspect I know no one will notice. They were trying to shoot these scenes as if they were night and had blacked the windows out. That was all fine, because it totally looked like night, but there was one bird that was perched in a tree outside the house that was just making this insistent, very distinctive call. They were going, ‘Can we do this? Is the bird going to get in the way?’ and people were saying, ‘No, we’ll be able to take out a particular frequency.’ It was definitely getting in the way.

I just thought it would be funny, almost to annoy Alex in a way. During a break in filming, we went to look at the church, which is just around the corner, and some of the other places. They all really were in this one location. This bird was going [off] again, so I just got out my phone and I recorded the birdsong, and I’ve used it massively in the score, which obviously makes no material difference. No one’s gonna know that’s the bird. But I recorded it and then pitched it down, which is a very weird thing to do with birdsong. Slowed-down bird song is incredibly complex. To this day, I still don’t know what bird it was, but it was one of those very high-pitched and warbly [birds], and it just sounds so odd slowed down.

That recording is a recurring thing throughout the score. What it does, I think, is it gives you a creative license to [say], “I’ll go with this, because it has a real connection,” and it gives you the confidence to put something into a score that you might not otherwise. Even though literally no one’s gonna know — people probably won’t even know it’s a birdsong — but it provides a creative impetus that I thought was quite a fun thing to do as well.

BTL: It starts as a joke that ends up working and being used.

Salisbury: It’s there in about 80 percent of the cues. This weird, slowed-down sound is that bird. Maybe not 80 percent, but it was a very prominent part of the score.

BTL: That’s a good transition to ask about the vocals since there are many vocal-driven cues. You mentioned the countertenor you worked with, but there’s also the moment in the movie when Jessie sings into the tunnel, which is amazing in the movie, but it was also used in the trailer. What was involved with creating that?

Salisbury: That was a late idea of Alex’s. I can’t take any credit for that as an idea, obviously. I was walking the dog, and I got this phone call from Alex saying, ‘We’re heading to do the tunnel sequence, and I’ve had this idea where Jessie’s gonna sing some notes, and they’re gonna echo back, and then she’s just almost gonna sing over the top of herself and create this music.’ I immediately said, ‘God, that’s a fantastic idea, and we’ll be able to make it work sonically.’ And he said, ‘What should she sing?’ And I said, ‘Just get her to sing something natural.’ She’s a fantastic singer, obviously, so the main thing is to make it not too musical. She’s just someone walking in the woods, liking the sound of their own voice, [as] we all do. We suggested a very simple four-note thing. I’m not even 100 percent sure if Alex remembered those four notes that she sang, but we certainly got them overdubbed again. Some of that tunnel sequence is the real notes she sang. Some of it we ADR’ed afterward.

Alex has got to take credit for that, really, even to the extent that he was impatient to get it done. I was very busy working on another part of the score, so he got the Music Editor, Rachel Park, who definitely deserves a mention because she got the clips of Jessie [and] what she’d sang in the tunnel. I’d suggested those first four notes, and she pitched them and then sort of created this template that Alex then presented to us and said, ‘I think this will work.’ We said, ‘Yeah, the idea is fantastic.’ Of all the pieces of music in there, a lot of credit for that one goes to Alex himself and the music editor and then we constructed it musically in terms of harmonically and stuff like that.

To be honest, me and Geoff took a bit [of] convincin3g about that, because we were very involved in the horror aspect of the score, and it becoming more and more tense and more and more leading you towards that final act. We were very conscious of how to get from the start to the end. We did feel like there was a danger that you are letting people off the hook with what is essentially a sort of semi-beautiful, simplistic beauty thing. Alex is like, ‘No, actually, we do need [to be] lett off the hook there from the countertenor.’ The countertenor was becoming a bit oppressive, which was sort of by design. The countertenor almost represented the Green Man and the subsequent aspects — I won’t go into spoilers — and it had a perfect narrative reasoning voice in there, and then we were able to weave tiny bits of her.

It was my wife’s idea, actually. Right at the very end, I was playing our version of the score, and she said, ‘Why don’t you finish literally with Harper’s voice? She’s the one who’s come through this.’ It originally ended with the end phrase of the countertenor theme that we’d built up. We were doing a recording session with Jessie Buckley anyway, to ADR the tunnel stuff, and so the last notes you hear of the score are actually Jessie Buckley as Harper, singing her echo refrain, which seemed very apt again.

BTL: In the first teaser A24 made, they used that so well, because it was so unique. I’d never seen or heard anything like it before.

Salisbury: Well, that’s the thing, I suppose. Because it’s such a simple idea, we didn’t realize it would be so effective. The idea of voices echoing through the score — whether they were Jesse’s, whether they’re the countertenor, or there’s another voice that joins, a lower voice, which is actually my voice that joins later on — it is this repeated layering of vocal phrases that became a very integral part of what we were doing, really.

BTL: It seems like the score is very processed, so do you use granular synthesis or just synthesis in general on things?

Salisbury: Sort of by the nature of practicalities, but I think it worked creatively as well. The practicalities of lockdown, where I’m recording a countertenor, and I’m 200 miles away from him, and we couldn’t really get a choir together. I’ve got these demos that we were all amazingly happy with, and it perfectly encapsulated what we wanted, which was this odd, very beautiful, hopefully, but also slightly unusual and arresting sound that you couldn’t quite pigeonhole as either male or female. That was the sort of idea and [it] has vague medieval resonances, as well as church resonances. It was mainly the sonic quality of a male voice, singing in a female register, that also has very interesting tie-ins with the themes of the film.

By the very nature of just getting these recordings and having a big bucket load of stuff that I got this guy to sing, we then had to make a score from that. There had to be really tense bits, there had to be almost sort of action music bits. That is where, as you say, granular synthesis and messin’ about with stuff came into its own. One thing we always like to do — me and Geoff — is have a palette of sounds that you stick to throughout that give a film or TV show a musical resonance, their own distinctive musical language.

It’s always a slight creative to-and-fro. I think, sometimes, me and Geoff would like to do something with just two instruments [and] see if [we] can do a whole film with literally the small… okay, maybe not two instruments… but the smallest use of force possible. Alex is naturally drawn to richness and layering and covering every angle and sometimes getting very big and sometimes very small. We have this constant tension between ourselves, so the one way we get around that sometimes is to have a small number of forces. In Men, the only sounds used are the countertenor’s voice, my voice, Jessie’s voice, a sort of glass organ, crystal flashing, and the bird and a fox. That’s literally it — the sound of a bird and a fox. But it still needed this massive richness of sound, on occasion. That’s where you get into processing.

I hope that the idea is that you can create a really, really aggressive in-your-face horror chase sequence by processing the countertenor’s voice and turning it into a pulse, and yet it still feels like it’s part of the same score. I don’t know whether that’s true or not, but maybe again, it’s like me using the bird thing. It’s just a way of being sort of creatively confident with yourself. I think there is an element to that, I hope, in that yes, you’re creating these very aggressive policies, but they’re not synthesizers. We haven’t suddenly brought in a bank of Koto drums or whatever. You are still working from your palette. If our scores for Alex’s films do work — and sometimes they don’t, sometimes they do — I think there’s no one who’s 100 percent satisfied with what they do, but when they do work, it is that element of it being a distinctive thing for that particular film. We’ve tried that with every single thing we’ve done with him.

BTL: It’s interesting to put that limitation on yourself and make it work, rather than going, “We have to put a big orchestra in here.” I’m sure you have your own home studio there, and I’m sure Geoff has his own home studio. Do you ever work in the same room ever?

Salisbury: Always. Lockdown was a slightly strange experience because normally, we do sit in the same room — normally, my studio — to write, and then Geoff’s studio to record if we need. Geoff’s got a posher, bespoke recording studio; mine’s more of a writing room. Everything we’ve done up until lockdown, we had done more or less in the same room. It would sometimes be a case of me doing stuff or Geoff doing stuff, but we’d come together. It’s almost like you’ve got this block of clay that you’ve vaguely sculpted into something, but then we’d take turns chipping away, getting on the keyboard, or whatever. I’m mainly the keyboard player and the computer operator, but Geoff’s totally adept as well.

[During] lockdown we couldn’t do that. There was a period during Men, actually, and we were working on another horror series for Netflix called Archive 81, and no one could be together. We literally had to change the way we worked. It was sort of beneficial, in a way. There’s a great benefit to having a collaborative partnership, but sometimes, you find you’re almost making work twice as hard for yourself because there are two of you doing one person’s job. We ended up, really, with Archive 81 and Men, doing stuff separately and just sending it to each other. It was more, “I’ve just done this, I’ll check it to you. What do you think?” “Yeah, that works. Maybe change that bit there?” Or “have you tried that from what I did yesterday on there, and have you tried…?” It was much more productive, in a way.

I think the future will be a combination. Now we’re back [and] able to work together. I’m hoping we will take some of that lockdown stuff, so we’ll be able to keep doing stuff on our own and then bring it together. But also, I did miss sitting in the studio. Some of the best things we came up with in Ex Machina and Annihilation were flukes of Geoff messing around on a synthesizer and me going, ‘Wait there, I’m going to record that’ and things like that. That sometimes can only come with being in a room together. Now, hopefully, we’ll navigate a way of getting the best of both worlds.

Men is now available to buy or rent on VOD and all major digital platforms.