![]()

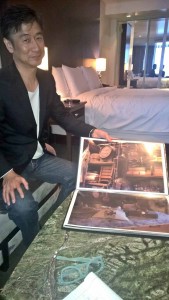

And those films are among the ones that production designer Yohei Taneda cites as influences when working on his second collaboration with Tarantino since Kill Bill, Vol. I.

“When I was a kid, I loved western films,” he told us, working mostly through a translator, during a recent L.A. visit. “I loved them very much.”

Indeed, he cites the particular “situation” of The Hateful Eight – essentially a chamber piece, once the various characters arrive via stagecoach at the snowbound “Millie’s Haberdashery,” the one-room general store that most won’t be leaving – as being similar to Shane.

In Shane, that would be the saloon and store where much of the action and showdowns ensue – though those characters are able to come and go.

But for Taneda, it wasn’t just a matter of riffing on previous films. Spaghetti westerns represented a “mixed culture” view of the West – Italian directors, usually working in Spanish locales, commenting on American mythology. And it was also “challenging and exciting” for Taneda to bring his own influences to the task, especially given his background in not only numerous other Japanese films, but animation design in productions like Ghost In the Shell 2.

Animation, he allows, typically tries to create 3D spaces within 2D drawings, whereas film he likens to a series of photographs, or perhaps paintings. The way light was thrown in the work of Vermeer, for instance, he cited as another cross-cultural influence.

There were also research trips to the Autry Museum, but ultimately, he allows, the design process is “very similar, whether you’re doing a period piece in Japan or China.”

Or, of course, in Minnie’s Haberdashery.

“In Quentin’s films,” he continued, “the set is not just the set. The set is one of the characters. The Haberdashery is not just the Haberdashery; it’s Minnie’s history. The focus (in design) was on Minnie’s backstory.”

“In Quentin’s films,” he continued, “the set is not just the set. The set is one of the characters. The Haberdashery is not just the Haberdashery; it’s Minnie’s history. The focus (in design) was on Minnie’s backstory.”

We only see the actual Minnie in one sequence in the film’s chapters. She and her family are otherwise “ghosts in the shell” themselves. Though in the film, that set-as-story, replete with throw rugs, and a bricolage of furniture, furs, jars, pots, liquor, candy, crates and more, was perhaps a little toowell told, at least initially.

“I love detail,” Taneda said. “Quentin told me this would be in 70mm, so every detail is important.”

Yet the large interior where most of the film takes place “was actually set-decorated a lot more, but it would get in the way of them walking around.” So as Tarantino blocked his actors, he found himself removing some of the furniture, crates and furs, in order to accommodate more movement.

That brought a kind of clarity one might liken to the practice of Zen: “By taking things away,” Taneda said, “there was more depth and more meaning.”

All replete with Vermeer-like light. Through a spaghetti-western filter.

It only seemed fitting then that our time together ended both with an Eastern-style bow, as Taneda thanked us for an enjoyable conversation, followed by a Western handshake.