If you’ve chosen to read this article, you probably know at this point that Spider-Man: No Way Home unites the three best-known incarnations of Peter Parker — OG star Tobey Maguire, the amazing Andrew Garfield, and current webslinger Tom Holland. Seeing the three of those heroes together was certainly one thing, but hearing them was definitely another.

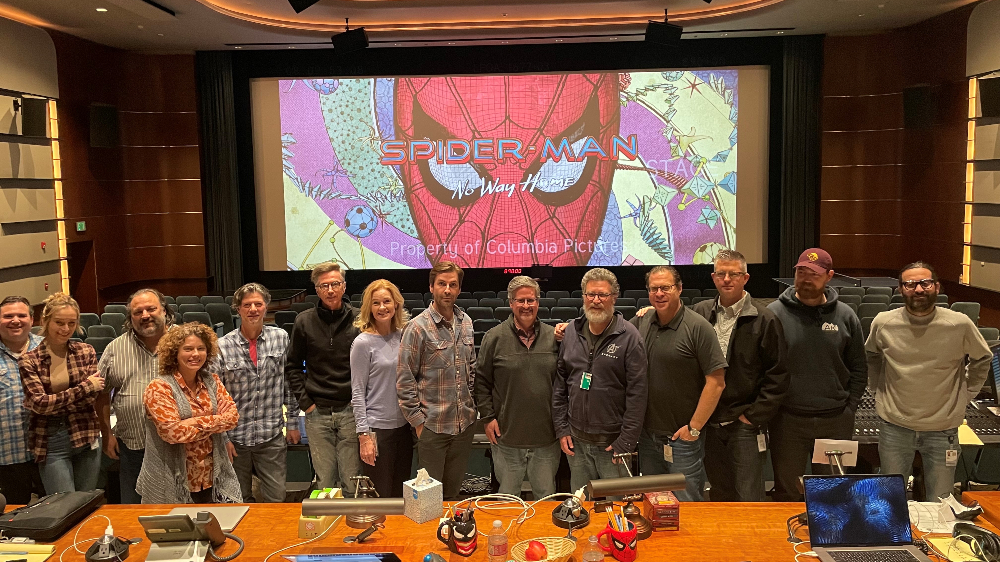

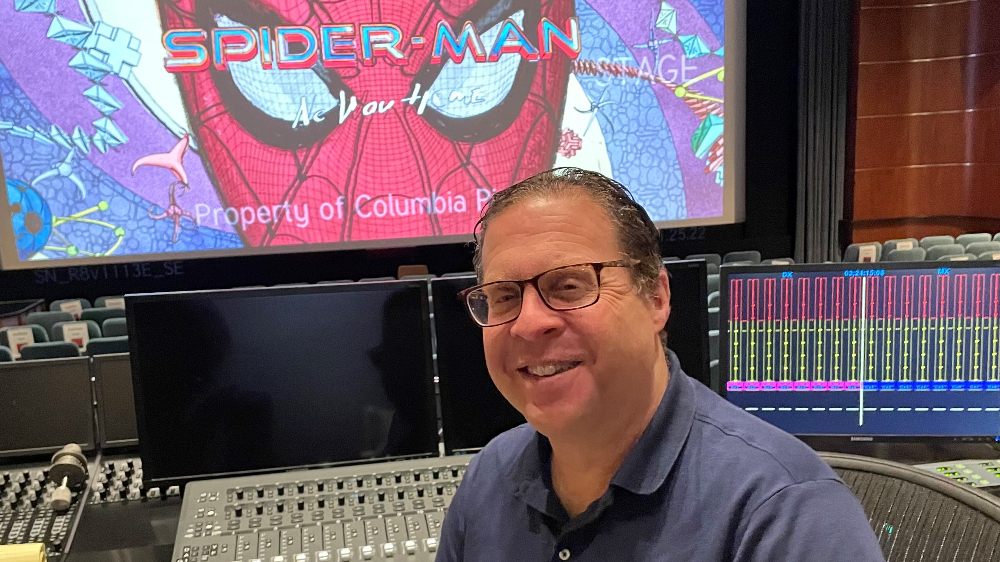

“We were given the honor – and it is an honor – to have all of these different characters merge into one film,” says Steven Ticknor, supervising sound editor of Spider-Man: No Way Home. And in honoring all the cinematic Spidey incarnations that preceded it, “it was really important to (director Jon Watts) that we kept, sound-wise, some traditional audio from the previous films.”

In crafting that “soundscape” to reflect all the various Spidey incarnations, and villains, in earlier films from directors Sam Raimi and Marc Webb, Ticknor had actually “had the pleasure of working with a great team on the very first (film) with Sam,” and in it, he helped design the glider, or at it least its aural components, which Willem Dafoe’s Green Goblin swoops around on while causing lethal mayhem.

Precisely the same type of mayhem he returns to cause this time around, as well.

“So,” Ticknor says, “I had to look for the sound. We had back-ups,” most of them being, as you might expect, stored on media that was about 20 years old. He eventually found “a CD-ROM of it,” which might be akin to finding a Betamax copy of rare footage. But try as he might, the CD-ROM “wouldn’t mount” on the initial array of computers he tried on the Sony lot. This, of course, refers to computers that even had a disc tray to begin with.

But then, in one of the printing rooms, “I found a 10-year-old computer. [The disc] mounted, and I yanked it off onto a USB drive. It was a hallelujah moment!”

But additional hosannas would be needed to complete the process. “Then we had to take these old Pro Tools sessions, from all these years of work, then convert [them],” citing as an example the conversion of SD2 files into WAV format. “The workflow today is so [much more] sophisticated and so modern.”

As an example, he notes that in the era when Dafoe was first mounting the green glider, “ProTools could play 32 channels at a time [and] a lot of work would go into the mix.” Now, “ProTools can handle two thousand channels in one session.”

Just in time for handling a multiverse!

But as sound designer Ken McGill says, there was one center of gravity that had to sound right, no matter the timeline. “We had to be really clear; this is still New York. This needs to feel like New York at all times.”

The film couldn’t be shot there due to COVID, and as Ticknor emphasizes, “everything in this film had to be invented — everything. There was nothing authentic with the actual scenes walking through New York City,” which also included digital extras, as well as a panoply of taxi horns, construction sounds, ambient yelling and crowd noise, et al.

But it wasn’t just the expected Scorsesian, NY soundscape that needed to be authentic; even its fantastical elements needed to sound believable.

So, when Holland’s Spider-Man visits Benedict Cumberbatch’s Doctor Strange, who casts a spell on the webslinger’s behalf that goes amok, and starts collapsing parallel universes together, they still, as McGill says, “had to be really clear; (even though) Strange’s lair is in this sort of suburban New York neighborhood, this is still New York. This needs to feel like New York at all times.”

Even, or perhaps especially, with “the universe cracking; that was challenging and fun. All kinds of elements of glass and rock and sound,” were mixed into the culminating images, as the sky itself starts to sunder, and the story goes “from the real world in New York (to) the other end of the spectrum, to out-of-this-world sounds.”

Clearly, the work has resonated in our world, as Spider-Man: No Way Home has gone on to become one of the highest-grossing films of all time, and during a pandemic, to boot.

“It really is a tribute to the movie industry that this film brought people back to the theater,” Ticknor says, and while he notes that “we’re on the sound side of it,” he and McGill are quick to credit everyone else involved, not only on their sound team, but editors, the camera department, all the way up to the writers and Watts himself, for the creative leeway that allowed them to arrive at the story they all conjured.

“The fact that people all around the world accepted this film” Ticknor adds, “we’re so proud as a crew to be part of that experience. That’s really the thing for me most of all. This gave a break in the sense of all that’s been happening for the last two years.”

And perhaps some hope that this may not be the only available timeline of events, after all.