When filmmaker Matt Reeves decided to director The Batman, he knew he’d need the help of Weta FX, the company that was instrumental in creating Andy Serkis‘ Caesar, as well as his primate friends and foes, for Reeves’ Dawn of the Planet of the Apes and War for the Planet of the Apes — both of which earned Oscar nominations for their incredible visual effects.

VFX Supe Anders Langlands was still fairly new at Weta when War was coming together, having just joined the New Zealand-based VFX house after spending more than a decade at MPC — first in London, and then Montreal — but he hit it off with Apes VFX Supe Dan Lemmon, so it made perfect sense for them to reunite to help Reeves achieve his vision for The Batman.

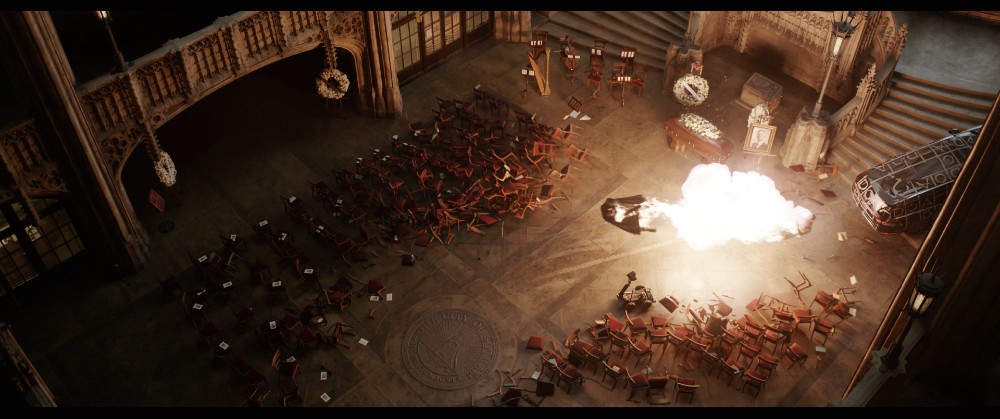

Weta played an integral part in The Batman’s breathtaking highway chase that saw The Penguin (Colin Farrell) try and fail to outmaneuver Robert Pattinson’s souped-up Batmobile. It starts out as a conventional car chase and then quickly swerves out of control as they race against oncoming traffic, leading to an enormous pile-up of 18-wheeled vehicles. All of that happens in Gotham’s ever-present rainfall, which would have been far too precarious to achieve in any practical way on camera. Weta also played a part in creating the film’s expansive shot of the Batcave as well as the funeral sequence set in a cathedral-like City Hall.

Below the Line previously spoke with Langlands last year for Disney’s Mulan, for which he received his second Oscar nomination, as well as for Zack Snyder’s Justice League. Weta FX’s dazzling work on The Batman is just as likely to land them back in the Oscar race next year, as it adds so much to the undeniable visual spectacle that Reeves has created as he introduces audiences to a new version of both Gotham and the Dark Knight.

Below the Line: I know you worked with Matt previously on War for Planet of the Apes with Dan Lemmon, the overall VFX Supe. When Matt came to Weta to do this one, was it always for the big car chase sequence, or was there other stuff you were working on for the film?

Anders Langlands: Actually, it swapped around. We weren’t originally slated to do the car chase scene. We were supposed to do a bunch of set extension stuff around Gotham, and some of the city square extension stuff, which ended up going to ILM. They gave us the car chase instead. We still had a bunch of other set extension work like the City Hall for the mayor’s memorial scene, the Batcave, and a bunch of fight work with the fisticuffs he’s doing, and then CG bats at the end as well. The car chase was certainly the biggest one, which I wasn’t initially preparing for when we first started talking about it, and it completely changed what we were thinking about. It was very exciting, because I hadn’t actually done a car scene before, so it’s nice to do something new. It was certainly a thrilling sequence, so it was great to be involved with it.

BTL: It’s definitely an amazing action sequence that blows people away and gets audiences excited. How do you prepare for a scene like that? Are you working from very early in the pre-vis stage on that?

Langlands: Matt and Dan were pre-vising it before it was shot to work out the story beats and stuff. Third Floor did a lot of stuff there, both before it was shot, and after it was shot as well to try and to figure things out, and then we ended up taking over pre-vis very early on after the other shoot was done, mainly so that we could actually get into it. This was a very tight post-production schedule on this one. We didn’t really have time to wait for a pre-vis team to do it, and then [have] us dive into it after. We were able to get started on animation early because there were a whole bunch of beats that Matt needed to work out. I think they were limited in a lot of ways, in terms of what they could get storytelling-wise for some of the shots, because they need to know where you can place cameras and stuff. They had this long section of highway to cover, so a lot of shots are practically-mounted on vehicles or camera cars, but then there were a few beats we needed to really try and flesh out in terms of helping us understand what’s going on.

It starts off fairly sort of simple — Batman’s chasing the Penguin — but then we get onto the highway going the wrong way, and then Penguin sets off this chain reaction carnage over quite a long period of time actually. It’s like a car crash that goes on for a good minute. Matt’s very particular about having things make sense geographically in particular and the staging of everything. We had to do a lot of work to try and place vehicles in the audience’s mind and then see them carry across multiple shots so that everyone can understand where everything was. Originally, when the truck goes up in flames at the end of the climax scene, that was originally a different vehicle. It was like a van that was transporting explosives. There was a little mark on the van that said “explosive materials” on it. With everything being very dark and the rain, there was no chance for the audience to get that, so we ended up replacing it with a fuel tanker to make it much more obvious where this huge fireball was coming from.

There are a lot of things like that we’re trying to work out, and trying to track all those things so that the audience could understand what was going on, but also create these individual story moments where Penguin sets this thing off, Batman’s dodging it, and trying to tell that story in a clear way, which can be a challenge. A lot of work for the start of the scene was mostly about adding rain [and] making it wet, because they shot it mostly dry for obvious safety reasons. By the end of the scene, once that big pile-up starts and Penguin first slams on the brakes, it’s pretty much full CG from that point on.

In order to tell the story Matt wanted to tell, we needed to create a lot more than was first anticipated when Weta was trying to figure this out during pre-production. We had to create quite a lot of shots in order to be able to get the story across in what is a sequence of quick cuts. When you’re dealing with shots that are 10 or 15 frames long, it’s quite hard to tell a coherent story with that little screen time. It was a huge effort from Dennis Y00‘s team in animation to really refine all that storytelling. That fight between making everything feel big and heavy. We’ve got these big vehicles giving this sense of weight, so it feels real, but also trying to get all this action across in a very short amount of time, to get the story told. There’s a tension there that they worked really hard at resolving.

BTL: What are they giving you from set to work with as far as plates? Are they just filming a lot of trucks and cars painted green?

Langlands: No, they had 60 or 70, just a lot of vehicles. They had shot at Dunsfold Aerodrome in the UK, so they had like half a mile of runway with streetlamps down the side and dressing — like highway signs and what have you — and it was just dark on the outside. They had all the vehicles going up and down the road. We were initially thinking that we would be adding in a few vehicles here and there to increase how busy it felt, adding vehicles on the opposite side of the road when they didn’t have enough to do both sides at the same time in some cases. They set out to try and get as much as possible practically, but if you set out with the intention to try and get it practically then actually the integration becomes a lot harder after the fact. That’s one of the reasons why I ended up replacing so much of it digitally, because it’s just easier to do that than try and integrate when you don’t have huge green screens and other things to help that work.

I think they got a large chunk of it. It’s only once the action really starts to unfold properly later on [that] we needed to go in and give it some help to get the action beats across in the way Matt wanted. They’d shot a version of everything and they were kind of limited because they could only go so fast and things couldn’t get so close to one another for safety. There were plenty of times when they kind of got the shot, but it didn’t really do what he needed to do in terms of the excitement, the speed, the danger. What was great though is that… obviously, your visual key standard for the film is Greig Fraser‘s cinematography. It looks stunning, so having plates for all that stuff with the vehicles in it, even if we were replacing everything or changing things around was just an immense help. It made it much, much easier to get the scene looking like how everyone wanted it, because we had a visual template there from the DP straight off the bat.

The whole film is lit in a very interesting way, using lots of light sodium vapor lights and fluorescents and sources that have a peaky spectrum. For instance, with the sodium vapor lights you have on the highway, because it’s not like an oil incandescent light source, it emits in a very narrow-band wavelength. What that does is it flattens color often, so you look at the color of things for that sort of information, that’s one of the reasons why everything’s being replaced with LEDs now, because it doesn’t have this effect of just flattening all the colors, so you have a very distinctive look that would be pretty hard to actually reproduce.

Fortunately, with Manuka Render, we render everything with the full spectrum of light properly, so reproducing those effects is actually much easier than would be in a traditional, what you would call an RGB renderer. We spent a lot of time just trying to get those spectrums matched up to what the practical sources were doing so that what we were rendering would have that same sort of flattened monochromatic fields of the colors that the real photography did, and that made a huge difference for just making everything feel integrated and nice. The chase was a more traditional sort of visual effects workflow and adding rain to everything was a big part of it. Rain is an interesting one because it’s one of those things where you just… Oh, yeah, “add rain” — it sounds really simple, right?

BTL: I just assumed you had a button that literally says “Add Rain” and a knob that you can control it with.

Langlands: No, it’s not quite that easy. Adding rain in visual effects shots is something you do quite often, but traditionally, you have a static camera, right? When you’re shooting landscapes, and they want rain, there are ways to do that with elements. We did a lot of that in War for the Planet of the Apes. In fact, in some of the early scenes, there are a lot of dialogue shots, and it’s raining, and there are different ways of doing that that are relatively simple. None of those work when you’re driving 100 miles an hour down a highway because you’re moving through the rain as you go. Ultimately, the requirement was [that] Matt needed the scene to feel super-dangerous. It’s gotta feel terrifying. If you’ve ever driven through a rainstorm down a highway, you instantly get a little bit nervous. And then the thought of all of this unfolding around you… you clench your cheeks a little, and it’s a bit nerve-wracking, so that was adding to the whole excitement of seeing the danger there. As I said, it’s mostly shot dry, so we had to do a whole bunch of different techniques to try and get that level of wetness there.

The main one is essentially just simulating falling raindrops, just filling as much as you can with CG raindrops. It’s actually really fascinating how they actually work because you think of a traditional raindrop, you think of a teardrop shape, right? That’s not what a raindrop looks like at all. They’re essentially falling spheres of water, but they oscillate as they come down, so they’re like growing and shrinking or stretching and squashing in either an up and down or side to side way. And doing that very quickly, multiple times a second or several times a frame even, so what that means is that when light hits it, rather than getting just a straight like motion blur streak, you get these broken up shapes from it, because [it’s] oscillating while the camera shutter is opening. You see it much more often in, like, movie rain, when they’ve got a rain machine, and they’re dropping big globs of water that are much bigger than a real raindrop. It becomes a really distinctive part of the look. Because there are a lot of scenes that they shot with rain machines, trying to get that same look to it becomes very important.

We did a lot of work to make that look real. We started off trying to actually simulate it directly, but that turned out to be much too expensive to render. So we made an approximation to that. Even that, once you got a cheaper version of it, you’re still having to simulate 200 million raindrops just to go 40 meters from the camera. Once you get to that level, that starts to push the bounds of what’s actually possible to render to make the image, so there’s always that tension of wanting to push it back further to get the rain in the streetlights, but not actually being able to do it too far.

That was the main one. The other big things that we were doing were any mist and spray from the cars, from the wheels and then, Beck Veitch, our compositing supervisor, her team came up with neat ways to add, like, little rain splashes onto the ground in an efficient way. If you want to add CG onto something that’s already in the plate — like, if they have cars already in the plate — then you have to track it and create an accurate model for it. If you’ve got 60 vehicles going down the road and you want to add little splashes onto everything, that becomes very expensive, very quickly. It’s a huge amount of work to try and track all that stuff, so we had to be very selective about which ones we actually tried to do and try and make more complex solutions for some of the pieces. We came up with this palette of effects, which is the raindrops themselves, the mist and spray coming from the select vehicles that we liked, and then these little rain splashes — what are called crown splashes — on the road surface.

In some shots, we’re just adding those onto a plate. In other shots, we’re just creating them completely digitally, because the whole shot is CG, and we can actually then simulate a bit more, because if we’re making everything, then we don’t have to track things. We can afford to do much more on some of those shots, but then you don’t want it to stand out from other ones. The whole scene was just a mix of these different levels of these different techniques to make each individual shot work. It wasn’t like there was like a one-stop solution for all the shots. Every shot was kind of its own little puzzle which is always the worst thing when you have a very tight post-production schedule. We had a very dedicated team working on it who pulled it all together, particularly in comp.

BTL: Did you start on this back in January 2020 at the beginning of the shoot, or did you come on later?

Langlands: No, we started doing parts of it early on, because I think we only knew that we were going to get the chase scene fairly late. The actual chase itself, we only got turned over to us I’d say four or five months before the finish, something like that. But we’d also be building vehicles and doing development work for the look of the rain and what have you. I think Dan and Matt were getting slightly nervous because we knew we were getting that sequence a little bit later. It took a long time for us internally to try and figure out the right balance of these different elements for making everything feel wet, that we could apply to every shot without making every shot super-expensive. You have to be selective about what you add, and also to still be able to create a consistent look across the entire scene, rather than having some shots looking different from others, because we’ve had to use a different set of techniques. Figuring out all of those ingredients and how to apply them.

The different shots took quite a while, and I think they were getting a bit nervous because we didn’t show them anything for a little while. Fortunately, when we showed him something, they loved it. That was the thing that I was probably by far the most nervous about when we first started the sequence was adding the rain and everything to all the shots because it is such a tricky balance. But the extra time we took getting the development work right really paid off because they never really questioned it in any shots. We never got any notes from Matt about it not looking real or not feeling wet enough and we had to add more stuff. It did exactly what he was after.

BTL: I know VFX and editing are interrelated aspects of post-production, so how does editing relate to what you’re doing at Weta? Are you giving Matt and his editors raw completed shots once VFX are done or longer versions of shots for them to edit? At what point are they getting stuff from Weta to add into the edit, and how much editing are you doing in terms of animating stuff in that sense?

Langlands: Pre-vis obviously drives a lot of that, because that obviously gives Matt something to cut with, and then, what you normally do is what you call post-vis, which is where you’re working on top of the stuff that they’ve actually shot. At that point, we start creating new full CT shots and start adding vehicles into plates, to start fleshing out the animation beats. But we don’t get stuff turned over to us until Matt’s done his first Director’s Cut.

There’s already some level of assembly done to the scene. Obviously, it goes through many iterations for the rest of it, but at least it feels like a film at that point. As we’re working through – particularly when we’re adding new shots – we’ll do a certain amount of “We need a shot to do this and that,” so we’ll jiggle around with the length of them and make suggestions about where we think stuff should be cut. We’ll animate them fairly long so that the editors have the most flexibility for where they want stuff to do. As we’re showing animation as it’s developed, even if we’re showing just one shot, we’ll be sending a short section of the sequence, so they can see how it plays out according to what our intention was when we animated it.

Of course, Matt and the editors might make a completely different choice, and then they’ll go away and work with it, and then we’ll get an updated sequence cut back from them, saying, “These are the in and out points for all these shots,” and then we update our working scene based on that. There’s a bit of to and fro, but really, we’re making choices as we’re animating stuff, but we’re not editing the film. So it’s always driven by editorial.

BTL: I’m glad you mentioned “post-vis,” because it’s a term I hadn’t heard previously. Does that refer to visual effects or animation applied to things that were shot on set?

Langlands: Pre-vis and post-vis are basically the same thing, which is just doing really quick animation passes just to block out shots, basically. Because everything’s a bit rough and ready, it allows people to try out lots of different ideas very quickly and to get an idea for the whole thing. The difference between pre-vis and post-vis refers to whether you’re doing it in pre-production or during post-production. Pre-vis you use to design a big action scene normally, so as part of the process of figuring out what your shots are, and how you’re going to shoot [them], and figuring out options for that. It can be a tool for deciding what camera angles you want, physically how are we going to get a camera where we need it to go to get the shot that we need? Is the shot going to have to be full CG?

And then post-vis, it’s the same process, essentially, in terms of generating images but working on top of stuff that’s been filmed already and normally done just for the purposes of that first director’s cut, after the movie has finished shooting, and a director needs to make their first cut to show the studio, if there’s a whole bunch of shots where there’s just a green screen, they need to have something there. In some cases, they can just use the pre-vis that they did before they shot, but if they changed things around when they were shooting, they might need to generate new material in order to fit with the plates they actually shot. It’s more about the difference in when you do it than anything else.

BTL: You mentioned that Weta also worked on background environments, both on the Batcave and the City Hall funeral sequence.

Langlands: Yeah, we did those. City Hall was a big hangar in the UK. I forget the name of the place now, but they used to make blimps there, apparently. They built a huge set, this big cathedral-like building, so we just built an extension for that. That was a fairly straightforward build. [Production Designer] James Chinlund had done a lot of work obviously designing the thing, and they had 3D files as well, which you could use as a starting point for it and match up to the LIDAR from the set scan, which was very helpful. We made a few changes based on what Matt wanted to do, like the design of the big windows changed a little bit in terms of Matt wanting it more like what you see at Grand Central Station. That environment was a nice one to build because there wasn’t too much wandering around during the development processes. It was fairly by the numbers.

The Batcave, we did a bit more development work on, just in terms of figuring out what that environment wanted to be and how big it wanted to be. There’s only really one big shot of the Batcave which is that first big panning wide [shot] when Bruce is riding in, which is pretty much full CG. They had a large chunk of the set built, and they shot a plate of it. That was shot in Leavesden, but because the stage wasn’t big enough with the set, they couldn’t get the camera quite as far back as they wanted it to be for the shot he wanted to get. We basically had built the entire thing anyway pretty much, so essentially, we completely rebuilt that shot in order to get the camera angle that Matt was actually after. That was a fun environment – it’s like the Wayne family’s private subway station underneath Wayne Tower.

We had it all roughed out in 3D from the Art Department, and we did a lot of work just figuring out how big the space was, mostly about that one shot. We really designed the space around that shot more than anything else, and then there’s a lot of time just trying to get the lighting roughed out and trying to fit in with the visual style of what Greig had done elsewhere, in terms of the pools of light stuff, but also making it bright enough that you can actually see something. Obviously, there are a lot of shots of Bruce looking at the computer and having dialogue with Alfred and lots of CG bats – they’re just hanging off the ceiling and flitting in and out throughout.

Both the Batcave and City Hall, I think the most interesting thing about those and with a lot of the film was just the lens work, the lenses were really gorgeous. A lot of it was shot on the ARRI Alphas, which is ARRI’s anamorphics I think they detuned with Greig. It’s quite in fashion at the moment, how we’ve gone from ARRI and others having spent a long time trying to make the perfect image from the lens, perfectly rectilinear, crystal-clear, super-naturalistic colors. Everything’s just perfect like what your eyes would see. But, of course, now that they’ve done very well at hitting that job, now everyone’s like, “Well, that’s a bit boring. We want the shots to have character… ”

Particularly for a film [in which] Matt’s leaning so much into the great crime-thrillers of the ’70s. You want to have a bit more character to the image, so there were the Alphas that Greig had detuned already, and then they had another set, which they detuned even further to reintroduce chromatic aberrations and reintroduce focus fall-off towards the edges of the frame. Some of them are just completely barmy in terms of getting double images everywhere. As a lens geek, it’s kind of fun to try and pick apart all these different artifacts that make the image so interesting. We’ve spent a lot of time recreating or trying to simulate a lot of those same things that we could then apply when we’re trying to integrate our work with the plates that they’ve shot. Matt always likes to shoot wide-open, very shallow depth of field on dialogue stuff in particular. There are entire sequences where it’s all these gorgeous, rich 4k in the background with this wonderful texture from these lenses. Recreating that was a lot of fun. It’s almost like painting at that point when you’re trying to compose shots with that stuff, because it’s all out of focus, but you’re just trying to place splashes of light and color in parts of the image to create this sort of dreamy impressionistic effect. It’s a really enjoyable way to work.

The Batman is still playing in theaters nationwide. And stay tuned for our upcoming interview with Production Designer James Chinlund, who talks at length about how VR was used to design some of the environments in the DC film.