At the relatively young age of 43 years old, British Composer Benjamin Wallfisch has already been nominated as Film Composer of the Year two years in a row at the World Soundtrack Awards, and nominated for a Golden Globe for composing the Hidden Figures score with Hans Zimmer and Pharrell Williams. He also earned BAFTA and Grammy nominations for the Blade Runner 2049 score he and Zimmer composed together.

Wallfisch has made a name for himself scoring the films of Andy Muschietti and David F. Sandberg, whose credits include the two It movies as well as horror films like Lights Out and Annabelle: Creation. So it made sense that Director Ron Howard would turn to Wallfisch to score Thirteen Lives — after all, what could be scarier than getting trapped in a flooded cave?

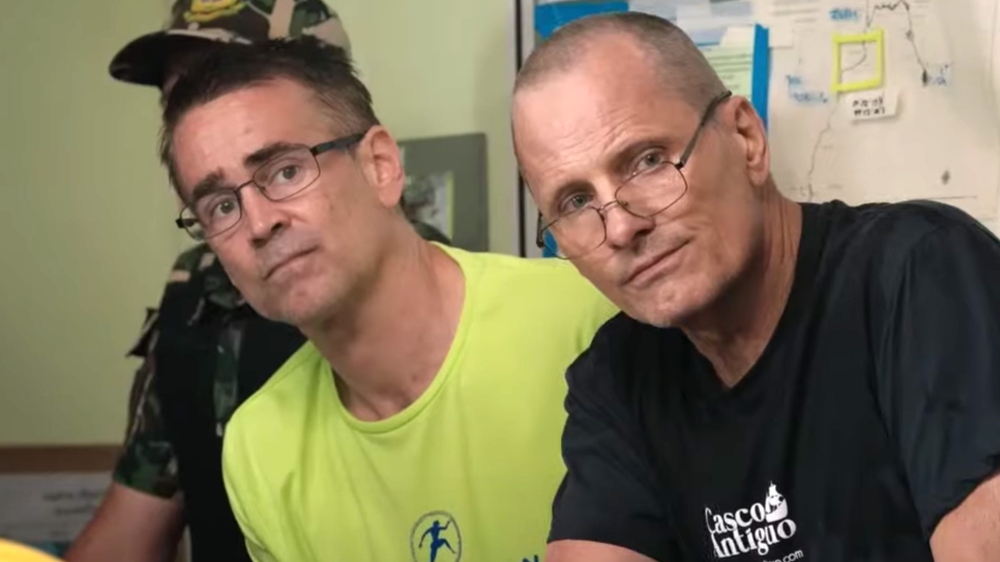

Produced by MGM and now streaming on Prime Video, Thirteen Lives is an incredibly powerful dramatization of the 2018 Thai cave rescue that captivated the world when a youth soccer team became trapped in the Tham Luang Nang Non cave after it was flooded by a monsoon. Howard cast stars Colin Farrell, Viggo Mortensen, and Joel Edgerton as the skilled cave divers who are recruited to figure out the best way of saving the team and its coach.

Wallfisch’s score works magic in building the tension of the rescue without ever going over the top on the melodrama, and Below the Line recently spoke to the composer over Zoom, where he offered a window into his process.

However, before we get to that conversation, we have a special treat, as we also recently spoke to Ron Howard, who had great things to say about working with Wallfisch on Thirteen Lives.

“One of the reasons I wanted to work with Ben on this was his comprehensive experience in horror,” said Howard. “When you talk to these divers about going into these caves, it’s kind of like the way somebody might describe going into a haunted house. They really don’t know what’s around the next corner, and what it’s going to mean to them, and there’s always this possibility of something happening, and they’re trapped. It’s just a reality of the process.”

“And then, you add in these kids,” Howard continued, “And I felt like it’s claustrophobic, it’s frightening. We wound up actually using less of his skill set in that regard than I expected, because the soundtrack itself created those atmospherics, and Ben was the first to identify that. Then we wound up using the music far more for the cultural specificity, because it’s a Thai story. He and a musicologist did a lot of work uncovering options and possibilities, leaning into the spirituality of the place, the mountain, that particular cave, and the lore around it. It was a really interesting, creative journey, and Ben really rose to the occasion.”

It was also important for Howard not to go too over-the-top with the score, as may have been the case in the hands of another composer. “This is an amazing event. It’s a very emotional one,” Howard explained. “It’s worthy of celebration, but I didn’t want to sentimentalize it. None of us did. None of us working on the film wanted that, nor did Ben. And so we guarded against it, but it meant that every time a larger orchestra would begin to play or a cue that he had developed that was a little too movie-ish would sort of present itself, it would be a little jarring. We were very selective about those moments where we really let the music play full out, but Ben could still be very musical, very affecting in ways that are almost subliminal.”

“[Ben] did a great job, and there was a lot of experimentation,” he concluded. “Often you build a temp score, and it gives you some guidelines, some examples, things that work particularly well, things that almost work, but don’t quite, but maybe there’s some instrumentation or something in the music that’s a clue. Mostly, we were finding that it was very difficult to find the right thing, and it required a lot of experimentation.”

And now for our interview with Wallfisch, where he gets into more detail about some of the things Howard mentioned:

Below the Line: I’ve really enjoyed the work you’ve done with Andy Musichietti and David Sandberg, as well as your work with Hans Zimmer on Dunkirk. The score for Thirteen Lives is just gorgeous and so evocative of the powerful story being told.

Benjamin Wallfisch: It’s so inspiring. It’s like the most heroic [story], but still moving. If you were to pitch the story as fiction, no one would believe it. It’s so extraordinary.

BTL: Before we jump into Thirteen Lives, I’m curious about your background. You’ve been composing for quite some time now. Were you a musician in a band or orchestra, or did you go to school for music? What got you into the world of film scoring?

Wallfisch: I was really lucky. I grew up in a family of musicians. Both of my parents are classical musicians — my dad’s a cellist [and] my mom’s a violinist. My grandmother and grandfather were both musicians on both sides of the family. I think it goes back three generations, so there’s a kind of family tradition. Music wasn’t just like an activity we did, like sports, it was kind of integral to the whole family culture. It’s something that was spoken about at the dinner table most nights. I think growing up with, especially my dad, his work ethic when it came to practicing the cello was so thorough, and he was always exploring. To this day, he’s still practicing the “Rococo Variations.” I still remember him warming up with some of those difficult arpeggios every morning at age five. 40 years later, he’s still at it, but he’s someone who commissions new works from composers. He’s commissioned more than 40 new pieces, so there are always composers coming to rehearse at the house. He had a duo with my grandfather, Peter Wallfisch, who was a great pianist. I would, as a kid, [lie] under the piano as they rehearsed, and I would just lie there and listen. Music has always been integral to family, for me. It was just one of those things where I started off in the classical world, following in the footsteps of my parents, first as a pianist, and then I did a lot of conducting in my 20s and writing concert music.

Film music, for me, has always been the thing that excited me the most when I was a kid, at least, and [I’ll] never forget hearing [the score for] E.T. [the Extra-Terrestrial]. Just growing up in the ’80s, [I was] very lucky in that incredible heyday of John Williams scores and all the rest of it. My first love, I think, was that [soundtrack].

I think it was more just when I practiced the piano — piano has always been my main instrument — I never really practiced. I kind of annoyed all my piano teachers, to the point where they would give me all of these exercises, which were very good exercises, but I just wouldn’t do them. I’d be much more interested in, ‘Why do these two chords from “Moonlight Sonata” just hit me in my chest every time I play them? What is this feeling?’ I would then spend hours finding other chords that do the same thing. It was just something I loved. The piano, for me, has always been like a partner. I would improvise and play just because I just found, completely by accident, I had no idea what I was doing as a kid [or] what it was called, but I just knew that those particular shapes, those harmonies, just created an emotional response.

Also, my parents were very generous in that, at age 12, they invested in my first sequencer, which was a hardware sequencer. This is in the early ’90s. It was a Roland MC-50 Mark II, it had a two-line LCD display. You could record 8 MIDI tracks, and you could only edit using, literally, just numbers and blocks and a little jog wheel. I spent hours on this thing. I had a guitar amp, a [Roland] JV-30 synthesizer, which was just [a] very basic General MIDI synth, and the sequencer. I should have been outside playing football and trying to date girls, but I was just in my room, figuring out how to make music with this thing. It just kind of went from there, and I’ve always found that I’ve just been a huge film nut, [ever] since I was a kid. It just kind of went from there, I guess.

BTL: Have you had your family at your disposal to record stuff that you’ve written, like if you need a string quartet?

Wallfisch: There were times when I was living in London [when] I would overdub [my Dad] many times to create a string orchestra. I still remember vividly discovering this idea of phasing. I learned a lot just from those early experiments. So yes, I was very lucky to have access to parents who played string instruments, but it was not like they were there all the time. We didn’t do it very often, for sure.

BTL: I know Ron has worked with Hans Zimmer quite a bit, and you’ve also worked with Hans, so did he introduce you to Ron, and was Thirteen Lives the first time you’ve worked with Ron, or had you worked together before on other movies that Hans did with him?

Wallfisch: No, [for] this movie with Ron, Hans very much recommended me for the job. I was just very lucky to be introduced [to Ron] through Hans, but I still had to audition for the job. It wasn’t like a shoo-in thing. We met and spoke several times before I was offered the opportunity, but it was an absolutely amazing chance. Hans — he’s my mentor and dear friend, and truly one of the most generous people I know, not just in terms of when he feels you’re ready for an opportunity [and] creating those opportunities, but also just in terms of [his] knowledge and his approach to storytelling. It’s very unique.

I remember when I met Hans — this is about 10 years ago — it was this moment [when] I realized that I needed to become a filmmaker rather than a composer. His approach to spending hours or weeks, sometimes, just honing in on what can be the central musical DNA that hits the story so fundamentally that can then really carry an entire score. It might be a very left-field concept, or something very experimental, or it might be simple as a theme, or it might just be an overall concept or a tone, or whatever it happens to be. Also, the way that Hans spends a lot of time writing music away from picture, before anything gets done to the frame… I’d never worked like that before I met him, so I was incredibly lucky. I’m one of many young composers who have benefited from that mentorship and friendship from Hans — he’s an amazing guy.

BTL: Did you start writing anything for Thirteen Lives even before Ron had started shooting? Did you get the script and start working on some ideas for themes?

Wallfisch: I did, actually. I was lucky to be brought on before the shoot had started, and I was being sent dailies. Ron made a point of calling me almost every week during the shoot, just to talk about discoveries he’d been making. I’ll never forget the phone call I got where he just said, ‘Ben, I need to tell you something. This movie, it can be summed up in one phrase: “An anatomy of a miracle,” and the idea that we are, in a very methodical way, unpacking the process that went into executing something that is truly miraculous.’

The way the film was shot, it’s quite documentarian in a deliberate way where he doesn’t overdramatize [or] over sentimentalize the story, but that tone comes very much from the style of cinematography [and] the style of acting. I only saw that when I saw the cut. You can’t really tell that from dailies. Prior to seeing the cut, I wrote a 25-minute suite, based on a few things. One of them was a song from the Northern Thailand region.

I had this idea… because the cave is in this mountain range called the Nang Non mountain range, Chiang Rai. Princess Nang On, the “sleeping princess,” if you see the mountains from a distance, you see the silhouette of a sleeping woman, and there’s a local legend that this is the sleeping princess. It’s her mountain, it’s her cave, and during the time of this rescue, local people were saying, like, ‘the Princess is angry, and it’s a test, and it’s up to the princess to release the children.’

It fascinated me, because it’s a very spiritual place. The whole of Thailand is, of course, and I realized, as a Western composer, I can’t just say, ‘Okay, let’s just get some Thai instruments and put some gestures in that.’ It had to be integral, not only to Thai musical culture but [the] musical culture of that region. I wanted to start from [a] place [where] the cave itself, the “sleeping princess,” had a musical identity, and that’s how the whole thing started.

I didn’t feel like I could write that. That needed to actually be a song from the place. I worked with a musicologist, Natt Buntita, who a friend of mine introduced me to, and she became integral to the process. She’s also an amazing singer, and you hear her singing in the final credits. She found this song, which is about 400 or 500 years old. It’s about the flow of a river being a metaphor for the flow of life, always going in one direction, and it was perfect. The melody had this beautiful opening rising fifth and falling interval. It was just immediately so evocative, and that became the sleeping princess theme in my mind. But, of course, you don’t hear that in the first half of the movie, because the moment you put melody or you put score, you can very easily break the spell of it putting the audience in the cave. We didn’t want to make it feel too much like a traditional movie or a piece of drama. In fact, it’s probably [the] most minimalist score that I’ve ever written, and how we place where there are not cues — the rhythm of the silence — was almost as important as where there were cues.

Also, where we start to introduce things like melody [that] you can clearly hear. There’s a little bit at the beginning, but it’s only when the first boy is rescued, that we really get into the thematic work. That “princess” theme is only actually heard in its entirety right at the end [over] the end credits, but it’s still sprinkled throughout — first, in the dark, in an almost alien way. As the first boy is rescued, the theme starts to become a little bit more present. I thought it would be the main theme. In fact, it’s not. It only occurs in its entirety at the end, but it has an influence in other places.

And then, the parents get a theme — that’s the cello melody you hear at the very end — and then there’s a ton of very experimental things. But that’s all to say that the suite I wrote before I’d seen the movie was completely different from anything that ends up in the movie, because it was much too much like a film score. [It’s] an unbelievably dramatic and very emotional story, so I went there and Ron, he loved it, but we started trying to put it against picture, and we realized it’s a different kind of movie. In fact, we saved ourselves a lot of time by just exploring what I would normally write for most of my other scores and realizing [that] this needed a very unique and bespoke approach.

BTL: I’m glad you mentioned that you didn’t want it to get too melodramatic, as that could definitely be a danger in scoring a movie like this. But most of what you ended up doing came out of the early discussions you had with Ron, right?

Wallfisch: Absolutely. It evolved, I think. We didn’t start there. I think we knew we didn’t want to be sort of heart-on-sleeve, because everyone knows what happened. The job was not to create an experience above what is already there, [because it] was already incredibly dramatic, and music does have the effect of adding a lot of emotion and drama even if you do something quite subtle. I think we were very aware of that, but the first place we went was, ‘Let’s attempt a horror score to start with. Let’s make this as terrifying as possible.’ And we realized [that] when you comment on what is already there, rather than come from inside of what you see, you can very easily get lost in the tropes of film music. Sometimes, that’s good.

For example, [in] the horror genre, there are certain things at a very technical level [that] you can push just a bit further than you may find elsewhere, and it becomes so extreme. Or, in a drama, there are so many ways I can give you… for example, just having a theme on someone’s eyes tell all the subtext. All of those things, we couldn’t do. We had to start from a place where just having this ticking, or a sound of a scraped cylinder, or the sound of a breath escaping an oxygen canister, or the smallest thing repeated in certain rhythms, is enough to create tension. That’s all to say we weren’t able to really get into the film score zone very often in the clearest way.

BTL: Did you work very closely with the sound editors or sound designers, because you’re talking about different sounds, so were you able to consult with them at all before the mix?

Wallfisch: Yeah, we did. It was very interesting because I learned a lot from that. There was an incredible sound team, actually, and this idea that underwater, sound travels much faster, and it’s very hard to locate where sounds come from. Also, the frequency range [of] the sound of rushing water occupies very much in the mid-range. We did have a discussion about how not to double up too much, and a lot of the musical sequences that happen underwater don’t occupy the mid-range. We did a lot of experimentation, where I was getting drafts of the sound design as it evolved, and I’d be writing with that pretty loud in my monitors, just to make sure that when it came to the dub, we’d be happy partners.

BTL: Do you usually attend the mix or final dub, too?

Wallfisch: I’ll go to the final playbacks, for example, but normally during the mix, I hand it over and let them do what they need to do. It’s important, I think, because as a composer, you’re going to be listening out for the music. I’ve learned over the years that it’s really important, once there are things recorded and mixed, to really just give full control over to the recording mixers and whatever comes in. And then, I’ll come at the very end and listen, and if I can be helpful in any way I will. I’ll give a few comments, but only if it’s relevant.

BTL: How do you usually write? Do you generally sit at the piano and work things out or are you at the computer with all different instruments at your disposal?

Wallfisch: I do a lot of work at the piano, and it’s funny, because as I get older, I get hit by ideas in more random places, just by thinking and contemplating something that there’ll be something suddenly, just a very clear melody that will come into my mind. My phone is full of almost indecipherable hummings, which eventually make their way into my scores. I think a lot of it, for me, is not being afraid to spend a lot of time, even if you have four or five weeks to write a whole score, I spend at least a week of that time just calmly allowing ideas to come and just experimenting at the piano and just building up a whole basis of core ideas before I would sit down and start writing it to picture.

The process normally flows really fast, and I also love to, again, not have any fear before I might even present something to the filmmakers, and then I will have no qualms about actually putting it [aside] and trying something completely different at the last minute. You’ve got to be very fluid and elastic with the process, I think, because filmmakers often come back with feedback where you do have to start from scratch. It’s good to get into the habit of just not being too attached to some of the ideas, even though you’ve got to really believe in them before you present them [and] be unafraid to just completely rethink [them].

I think a lot of that does come from having a big battery of theme or chord ideas, or whatever they happen to be, in the bank before you even attempt to start writing it to picture. You just never know where things may or may not work. It’s quite interesting how you subconsciously… if you do that brain dump of ideas at the beginning… what I thought was perhaps for a particular part of the movie or this particular character ends up being something totally different, or maybe ends up in a different score entirely. You just never know.

BTL: Do you orchestrate or conduct yourself when you do? Do you tend to do that stuff yourself or do you have other people you work with?

Wallfisch: Well, I have an incredible orchestrator, David Krystal, who transcribes my demos; I do a lot of the orchestration in the demos, but it’s very important to have a strong orchestrator on the team, just because there’s often very little time between the final sign-off and the recording sessions. I used to do a lot of orchestration myself for other composers when I was starting out and in my sort of apprenticeship. [But] I love what David brings to the table in terms of how he executes, since it’s just the subtlest thing — voicings and how lines are brought to life in the strings, for example.

I used to conduct everything, but more and more, I’m finding it’s more helpful for me to be in the control room with the filmmakers so that any ideas that happen on the fly can be immediately addressed, and there’s a sense of flow in that way. I do miss conducting my own stuff entirely, so I’m trying to figure out a way to do both — I haven’t quite nailed that.

BTL: That’s a good segue into my next question, because obviously, this was made during COVID. I’m not sure how you recorded this score, but I’ve heard every variation of recording score during a pandemic. When did you record this, and what were some of the things you had to bear in mind?

Wallfisch: We recorded this December 2021, and I was very lucky that we could do an in-person session. Everyone was wearing masks and sitting socially distanced, and it was actually the first session I’d done since the beginning of COVID that was with players — I was in the same building as them, at least. It was wonderful, actually. I had done four scores in the COVID style, one with everyone in their own kitchens, stacking things up. One where we could only have 30 musicians at one time in Australia, and we had to do just a lot of overdubs, and that becomes tricky for everyone, especially the players [who] can’t really hear the context. I’ve been so blown away by how these musicians just adapted, and the artistry has just never dropped. Everything they bring to the scores, no matter if they’re in their bedroom or at Air Studios, it’s still all there and uplifts everything every day.

BTL: I’ve been asking composers this recently because I get interesting answers… are there any scores you’ve heard recently that really blew you away?

Wallfisch: Man, that’s tricky… I’m about to do my listening and watching of all the movies of this year in one go — I tend to do it in December around voting time — [and] I think we’re in a very exciting time for film scoring. There are some incredible composers. I think we’re all trying to just push the boundaries. I think it’s a very exciting time to be doing this, and I struggle to pick out one, I think. What Hans did on Dune was absolutely fabulous, and knowing Hans’ process, I really loved that score and how he pushed things harmonically to a whole other place. I love what Trent [Reznor] and Atticus [Ross] are doing. I love Ludovico [Einaudi‘s] stuff. Anything which feels experimental but still has that raw emotional power. Not compromising is something I’m very attracted to, but it would be tricky to highlight.

I think there was one score, Homecoming, which is its own show. Homecoming [Season 2], that score [by Emile Mosseri] blew me away, and I wish it had gotten more attention. It was so brilliant, so experimental, and anyone who hasn’t heard it or watched that, go seek out Homecoming, the second season. That’s a great score.

Thirteen Lives is currently streaming exclusively on Prime Video, and you can listen to the entire score on YouTube.