Mike Mills might not be the most prolific of filmmakers, but the four feature films he has made have all had a significant impact on indie filmmaking, whether it’s his directorial debut, Thumbsucker, which received an Indie Spirit nomination and festival awards for star, Lou Taylor Pucci. Mills’ second film, 2010’s Beginners, garnered the late Christopher Plummer his well-deserved Oscar, becoming the oldest winner in Oscar history at 80 years old. In 2017, Mills received his own first Oscar nomination for 20th Century Women for his original screenplay, and now, four years later, he’s back with C’mon C’mon.

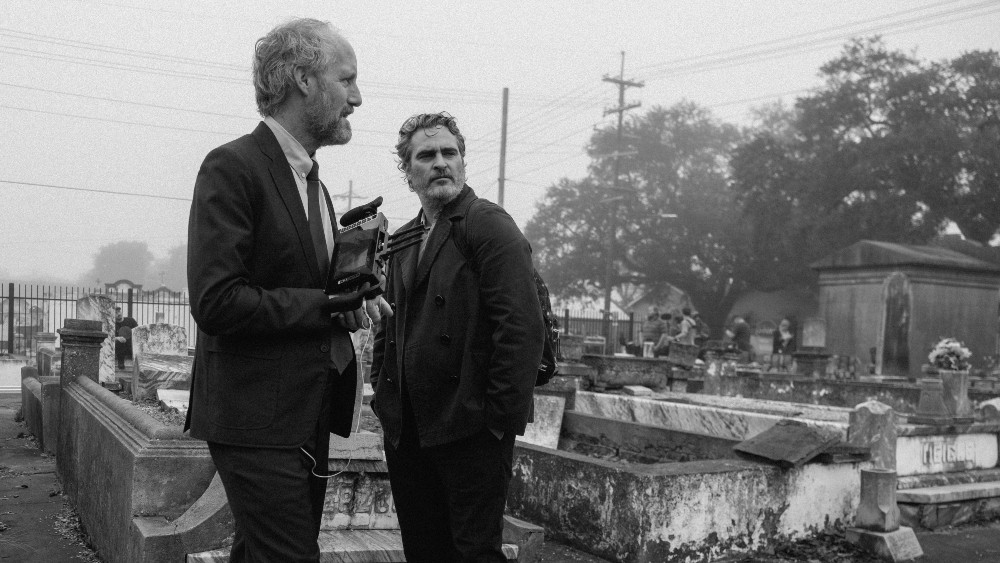

In the black and white film, Joaquin Phoenix plays Johnny, a radio journalist who is going around the country interviewing kids for a piece on how they see the future. His father is having mental health issues, so Johnny’s sister Viv (Gabby Hoffman) has to go take care of him. She leaves Johnny with her young son Jesse (Woody Norman), who Johnny ends up bringing on his trips to New Orleans and Detroit, as well as the two spending time in New York City together.

As with Mills’ other films, C’mon C’mon is another typically human character study from Mills that’s inspired as much from his own personal life from becoming a father, as it allows Phoenix to really shine in a far more grounded role than something like Joker (for which Phoenix won an Oscar). It also introduces the world to fresh young talent in Woody Norman, who few will realize is British, since he seems to come across like such a typical American kid.

Below the Line had the rare mid-pandemic opportunity for an IN-PERSON interview with Mr. Mills, sitting on the patio of his midtown hotel to talk about C’mon C’mon, including the aspects of it that allowed Mills to delve into documentary filmmaking.

Below the Line: I know with your last couple movies, Beginners and 20th Century Women, there was an element from your own life that kind of started the ball rolling, so was that the case with C’mon C’mon, as well?

Mike Mills: Yeah, yeah, it was my kid. They were six when I started writing it, but yeah, those experiences of being with my kid, and then, this contradiction or the intimacy of being a parent to a kid, and I wanted to write scenes about giving a bath and getting them fed and going to bed together and reading a story. I found that very powerful, and then, I also wanted to put that out in the world. I kept seeing the two figures like walking around and cities, and that intimacy then thrust into the big real world. I started writing after Trump and all that and the world of art. I somehow wanted to insert my fiction into the real world, so it’s also partly how the documentary with the kids came about, and those are just real documentary interviews.

BTL: I was wondering when you shot this, because I live in the neighborhood in New York City where you shot, and when I saw the pizza place, Scarr’s, I figured you must have shot it pre-COVID, since they’ve had one of those outdoor shelters that you see everywhere since COVID.

Mills: We shot in New York in December of ’19, and New Orleans and Detroit, we shot in January of 2020, so we finished at the very end of January.

BTL: That’s really amazing, but you were still doing the movie’s post under COVID?

Mills: So then COVID happened, and I had to edit remotely for like nine months, and I was doing Zoom homeschooling with my kid until 12:30 and then going into the edit.

BTL: One of the things that’s similar to 20th Century Women is that you faced the challenge of finding a young, unknown child actor. When you were doing the interviews for the doc, was that partially a way to find the actor to play Joaquin’s nephew, or was that something completely separate?

Mills: We really went to Detroit and found kids from this amazing school, and then we came to New York and shot mostly in the Lower East Side, and then to New Orleans. So those are all kids really from the places, and it wasn’t about… Woody’s an actor, and he came through casting. All those other kids aren’t actors.

BTL: Had he acted in stuff before?

Mills: Yeah, I should know more. He’s done work. He’s from London. He’s a British person.

BTL: With an accent and everything?

Mills: Yeah, his first trip to America was for this film.

BTL: I assume he knew who Joaquin was, as well.

Mills: Yeah.

BTL: Did all of the kids know that this filmmaker was really an Oscar-winning actor?

Mills: Some of the kids were more aware of it than others. We were shooting right during prime Joker campaign, but then, Joaquin is very powerful using the force, and so he’d be like, “I’m not the droid you’re looking for” and would do the interview, and it worked every time. Once they got talking, and Joaquin was so kind and respectful and careful and interested, that it worked out.

BTL: I would think most of the kids would be too young to see Joker.

Mills: But they definitely knew about it.

BTL: Let’s talk about the film’s cinematography. You obviously made a choice of filming in black and white, which is something that a lot of filmmakers are leaning in that direction. Did you shoot using one of the monochrome cameras out there?

Mills: We tested it. We tested a bunch of cameras, and we ended up going with just a normal Alexa Mini, because we didn’t really have a ton of money, and we were traveling around a lot, and we’re doing a lot of documentary stuff. There are only two of those Monochrome Alexas, and they’re very expensive. So, we just couldn’t afford it, and we looked at it, we tested it, and we were happy with what we can get on the normal Alexa.

BTL: On the creative side, what went into the decision to do the film in black and white?

Mills: I love so many black and white movies; I wish there were just more. But then with this story… there’s a lot of reasons. I kept thinking of it as a drawing, like with the immediacy and intimacy of a drawing, as opposed to a painting, and like the sketchiness of it, something that can only be black and white. And then, yes, there’s a documentary quality to this movie, but really, there’s also like a archetypal father-son story going on, which is ancient and almost like a fable. Black and white, I thought was a really good framing for that fable part of it. It takes you out of reality, and it takes you out of our time, and kind of transcends time a little bit. That was the main reason, this spectrum of going between a fable and a documentary. Black and white is kind of a great thing for doing that, because black and white is trippier than I think most people, because it’s really so abstract. We never see the world in black and white.

BTL: To that point, seeing the neighborhood where I’ve lived for 30 years, it took me a little bit of time to recognize some places, because obviously, I’ve never seen it in black and white.

Mills: We did all that stuff in Dimes Square. [Editor’s Note: This is a specific area in New York’s Lower East Side.] That was like our turf, right there. If you live right across from Scarrs, we were there every day.

BTL: You obviously write a full screenplay, and you don’t usually have improvising in your movies, but it does seem like this has a little more room to do that, so did you let Joaquin or Gabby or Woody do that a bit?

Mills: It’s a very written script, and very labored over, and then me and Joaquin did a lot of work on it together, which was very fun. I’m the kind of director that… I don’t want to [be] like, “I wrote this thing six months ago, and now we’re gonna execute it exactly like that.” I want to be alive to things I’ve learned or qualities of Joaquin and Woody and Gabby that I want to inject into the film, or someone I just met the day before, and they said something, and I want to insert that. So, I’m constantly rewriting, and then I definitely invite them to just go with the flow. If something leads them off the exact words, that’s fine. I’m much more interested in the energy than I am executing this predetermined thing that doesn’t hit everything. They’re saying most of my words. Once you give them a little freedom, every time they actually say your words, it sounds more real anyways. It just kind of livens up the whole thing. It makes it so if both the actors know that’s the game, then they listen a little bit more, because you don’t know what’s going to come next out of anyone.

BTL: How was it going through the script with Joaquin? I always got the impression he’d be an actor who would want to do that kind of stuff more on set.

Mills: I think it was part of him actually figuring out how to do the film, or if he wanted to do the film. We would read through it a lot together and just talk about it, and it wouldn’t be all just about his character at all. It would just be like two people who are in a student’s film, thinking about how would this work? And what about that? It was one of the most enjoyable things I’ve ever done, to have this really immersive, intense, thinking partner. It wasn’t like him going through his stuff. There was sort of like, “Oh, would that happen?” Or “If that happened, what would happen over here?” Sometimes that would happen, but it was very… I loved it. It was one of the funnier things that’s ever happened to me creatively.

BTL: Let’s talk about editing the film. You have all of these documentary interviews to put together, so what was the process and did it end up very much like your original script by the end of it?

Mills: In some ways, it’s a very linear script, because they go on this road trip, so it’s not like some of my other films where you can really do that. Then the kids’ stuff was interesting, because the kids’ stuff was documentary, right? So, it’s a typical process of, if you have an hour interview, and you’re gonna use like one line, like one statement from each kid. So that’s just a process of, “Oh, I’m going to cut an hour down to 30 minutes and then cut 30 minutes down to 10 minutes, and then 10 minutes down to five minutes,” and you just kind of find these nuggets. The interesting thing about editing this movie was the narrative scenes felt like a documentary. The performances are so relational and micro moves that actually do change a lot. It’s kind of like when you’re editing a doc, you’re carving away, carving away, carving away, but they’re like this real nugget next to this one, everything changes. It was nine months of remote editing at least — a little bit more, like 10 -11 months — which is a lot longer than I normally do. It was partly because it was sort of like a sea of really interesting opportunities, and then having them align was complicated.

BTL: Had you worked with the same cinematographer or editor you’ve worked with before?

Mills: Jen Vecchiarello worked on 20th Century, she’s the editor, and Robbie Ryan shot it, and I hadn’t worked with him before.

BTL: Is that decision mainly based on who is available, or do you like changing things up with different movies?

Mills: Robbie and I loved the Emma Stone Queen movie, The Favourite, and I like to shoot with no lights. I like shooting with just very little stuff, so I knew that Robbie was down with that. But then also The Favourite had a really strong, classic quality to me, especially in the framing of the close-ups. I knew I wanted that. It kind of goes with the use of black and white. I did want a touch of like Casablanca in this movie to me. The coverage is very clean singles. It’s very classic in a way, just the centered locked-off clean singles. That’s like as old as can be, that kind of coverage.

BTL: We should talk about the music, and it’s funny because I only learned about the work you had done with the National last night while preparing for this interview. I was seeing how long it’s been since 20th Century, and I saw this short film listed on your Wiki page, and I was curious what that was. And then, I saw that you worked on an album with the National and even have a song you wrote on there.

Mills: I produced the record.

BTL: Oh, really? Was it natural to have the Dessner Brothers do the music for C’mon C’mon, too? How did that come about?

Mills: Because that project happened while I was thinking of this one. That was a long project. We did the film with Alicia [Vikander], but then I ended up working on the record, and then the record ended up reinfluencing the short. It was this long back and forth. It was a very interesting, iterative collaborative thing, and when we’re doing that, they knew I was writing this, and I started talking about it, and we enjoyed working together so much. I really loved those guys, and I learned so much, hanging around them, so it seemed like it was totally natural. They’re super into filmmaking, and then this came around.

BTL: Had you ever produced a record before? I know you worked with bands on the visual side of things.

Mills: I really work on the scores for my movies and I’m very involved, and I’ve been around bands forever. I’ve been in many studios, and I’ve been in a band, so it’s more natural to me than even I might think. And they were very generous to let me play with their music when I made the short. They just gave me a bunch of their songs that were unfinished — they gave me all the stems — so I remixed a bunch of their music. They were interested by what I did, and then they invited me to come in and help finish the whole record.

BTL: Anyway, it’s great talking to you again, and while you’re not the most prolific filmmaker, you’re very consistent with a movie every five years.

Mills: I try to speed it up, but it never works.

C’mon C’mon will hit theaters nationwide on Friday, November 19. You can also read J. Don Birnam’s review. All photos courtesy A24. Photographer: Julieta Cervantes, unless otherwise noted.