It’s understandable if you missed this news late last week, as the country was further fraying apart, but here in Los Angeles, there was another major court ruling in the Rust case.

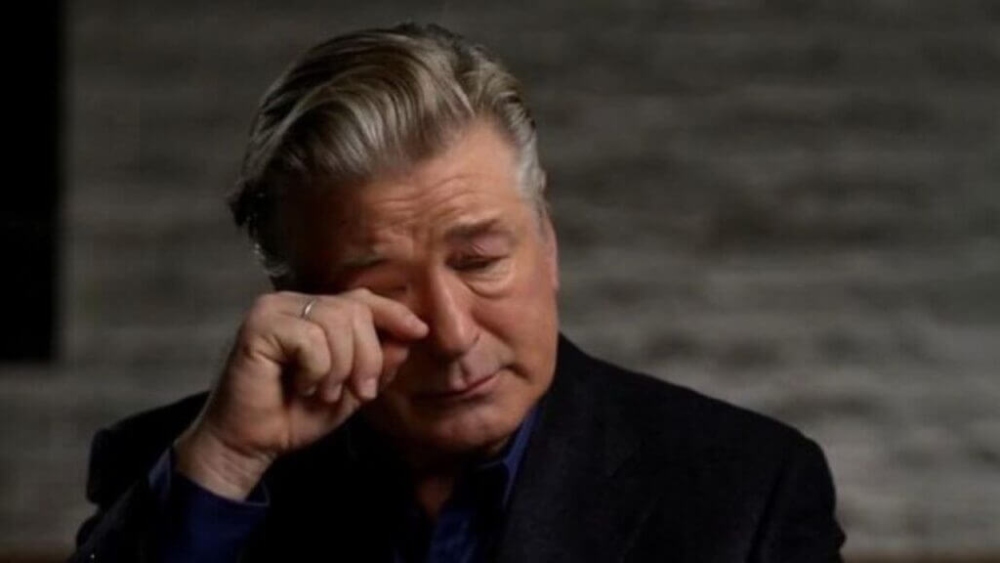

Superior Court Judge Michael E. Whitaker ruled that script supervisor Mamie Mitchell, “who was standing next to cinematographer Halyna Hutchins when she was fatally shot with a prop weapon fired by actor Alec Baldwin… can seek punitive damages from some of the producers who sought to have the damages stricken.”

Whitaker determined that “the first amended complaint alleges facts sufficient to establish despicable conduct carried out by moving defendants with a willful and conscious disregard of the rights or safety of others,” and further, that the four defendants (officially Rust Movie Productions LLC, Thomasville Pictures LLC, and producers Ryan Donnell Smith and Allen Cheney) “intentionally undertook a low-budget and cost-cutting scheme that was known to create unsafe conditions for movie production crews that resulted in moving defendants’ failure to ensure basic safety protocols with respect to the hazardous use of firearms.”

Whitaker also observed that safety failures included “intentionally [failing] to hire experienced crew members to manage and handle” those weapons.

That’s some language to have on a court record.

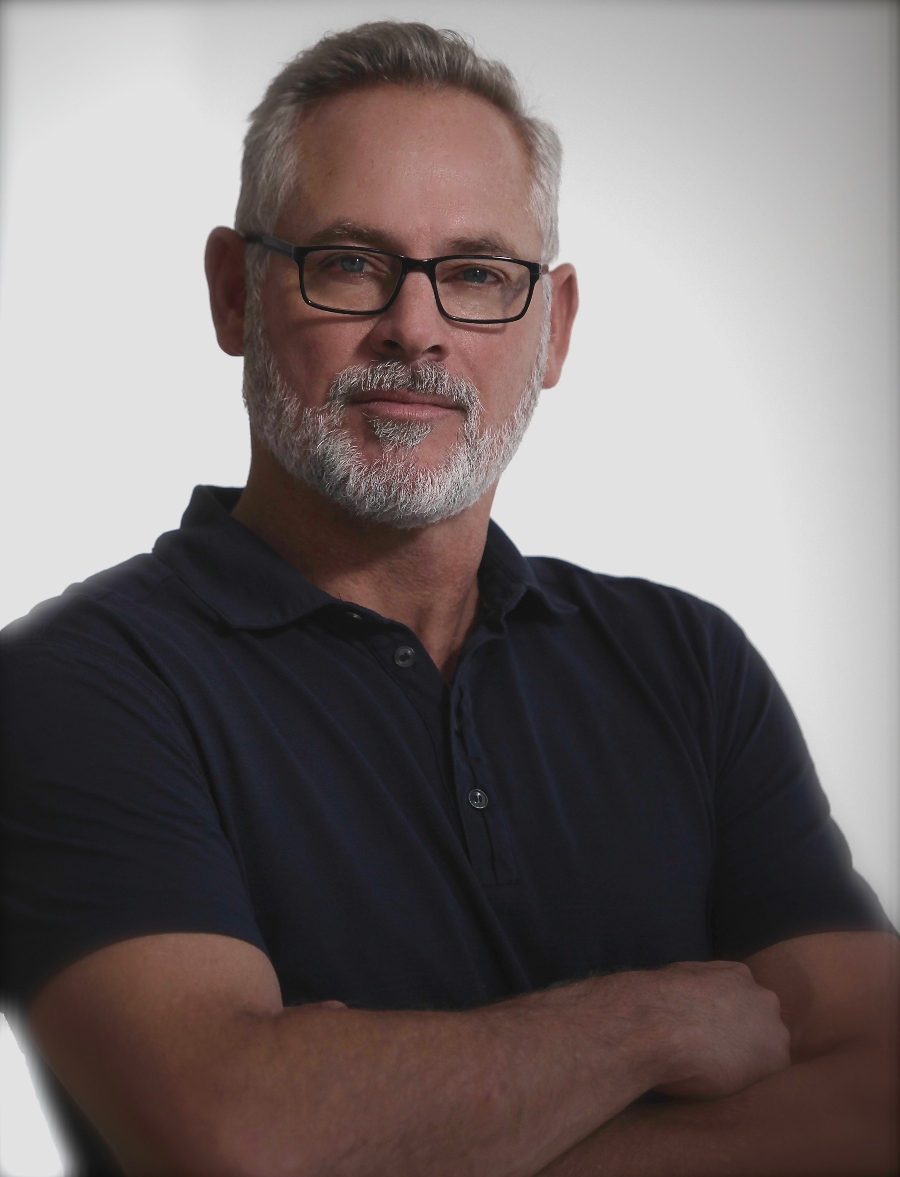

Coming in a week where the country was once again shattered by its inability to handle basic safety protocols for guns everywhere, the ruling and comments also brought to mind a chat we had earlier this spring with Cinematographer James Kniest, who has made a name for himself in the horror realm thanks to his collaborations with director/producer Mike Flanagan on Netflix shows such as The Haunting of Bly Manor, Midnight Mass, and the streamer’s upcoming genre series The Midnight Club.

Yes, there is a lot of “midnight” when you work in horror.

We’d caught up with Kniest just before the pandemic, around the release of the one-house locale indie horror film The Free Fall. The film follows a woman who wakes up from a presumed suicide attempt to find herself “cared for” by her over-controlling husband who never lets her out of the shadows (and not just metaphorically, given the various lighting setups).

We started talking about the popularity of horror in general and Kniest opined that “the nomenclature of horror has become more acceptable and palatable,” recalling earlier eras when “nobody really wanted to be labeled in that category” — Stephen King aside, perhaps.

“I was surprised, when I did a movie called Annabelle, to find the core audience is younger females. To me, that shocked me.” But given the general, permanent threat-awareness that most young women the world over live their lives with, perhaps not surprising.

In general, though, he finds that “audiences are more supportive” of the genre than ever before.

This in turn led us from talking about culture (and genre) in general to the specifics of indie filmmaking, since the Rust shooting was still fresh and we had more questions than answers at that point.

Kniest talked about his own coming-of-age in the fulcrum of indie cinema and its generally abusive working conditions:

“That was the environment I was indoctrinated in the early 90s — and it was unacceptable. We were hiring the unemployable. People had hall passes — especially men — to be abusive. There was this ‘mad genius’ hall pass — and if their work substantiated it, it was okay.”

But “we shouldn’t go to work with our neck bristling. So many people go ‘neck down’ if they’re being yelled at –– who wants to work like that? I sure don’t. How do you not want to inspire every single person on the set?” wondered Kniest.

“There used to be a mentality that the director, the DP, or the producer — you could never question their approach or their perspective. I’ve seen the industry change so much, in terms of the structure, and the politics. I call it ‘politricks.’ When I came up, we were pirates to some degree. It was a pretty rowdy scene really.”

Now, though, he thinks that that culture may be changing, horrific events like the Rust shooting notwithstanding. “There are a hundred and one different ways to do these things (now, and) different ideas are welcome… There are no screamers or yellers on set anymore.”

He also allows that in many cases, on-set incidents are “managed by HR departments that didn’t use to be there,” which he considered a good thing, overall. Except, of course, when those incidents aren’t really managed by anyone. Because people are still desperate to get into showbiz, and willing to put up with nearly anything to do it.

Including, evidently, the “politricks.” Deadly and otherwise.

Hopefully, there will be less gloom in June. See you then.

Mark London Williams is a BTL alum who currently covers Hollywood, its contents and discontents, in his recurring “Across the Pond” dispatch for British Cinematographer magazine, contributes to other showbiz and production-minded sites, and musters out the occasional zombie, pandemic-themed, or demon-tinged book and script, causing an increased blurring in terms of what still feels like “fiction.”

Mark London Williams is a BTL alum who currently covers Hollywood, its contents and discontents, in his recurring “Across the Pond” dispatch for British Cinematographer magazine, contributes to other showbiz and production-minded sites, and musters out the occasional zombie, pandemic-themed, or demon-tinged book and script, causing an increased blurring in terms of what still feels like “fiction.”

Mark London Williams’ Union Roundup column will appear every Tuesday. You can reach him to give him tips and feedback at [email protected]. He can also be found on Twitter @TricksterInk.