In Season Two of The Afterparty, which premiered July 12 on Apple TV+, former Detective Danner (Tiffany Haddish), Aniq (Sam Richardson), and Zoe (Zoe Chao) reunite to solve another murder mystery that unfolds the day after a family wedding—this time the groom has been done in. To get to the bottom of this whodunnit, a guest recalls their version of events throughout the 10 episodes, each displayed through a different film genre, beginning with the bride (Poppy Liu) in the style of the Renaissance era. Other genres include noir crime drama, a coming-of-age story, an erotic thriller, an epic romance, technicolor, and campy horror, to name a few of the choice compositions.

Director of Photography Ross Riege (WEIRD: The Al Yankovic Story, Grey’s Anatomy, You’re the Worst, and Rutherford Falls) treated each episode as a mini-movie with its own set of lighting and filming challenges. Following the stereotypical filmic tropes, the noir crime drama episode was shot in black and white, while the campy horror genre episode used low-ground fog effects. Riege and his team did a lot of homework in preparation, gaining inspiration from the classic films that came before and doing their best to replicate their color palettes and shooting angles even with the use of modern camera equipment. One episode was actually shot with the iPhone.

Born in Wausau, Wisconsin, the son of a professional opera singer and string bass player, Riege was very much influenced by music as an accompaniment to his passion for the visual. He gravitated toward that discipline while studying filmmaking at New York University.

Below the Line spoke with Ross Riege via Zoom video from his home in Los Angeles, where he geeked out on the tricks he used with modern equipment for each episode of The Afterparty, carefully constructed to pay tribute to classic movie genres, and the films he watched that inspired their looks. On an amusing note, Riege recalls working with the character Edgar’s (Zach Woods) pet lizard, which for the most part dutifully obeyed its wrangler, and what happened when it didn’t.

Below The Line: I see you are at home in Los Angeles but you actually went to school in New York at N.Y.U. Tell me how you wound up going there, and the trajectory it made towards your career?

Ross Riege: In high school, a friend of mine and I had a class where instead of just writing a report for our final, you could make a video, draw a poster, or whatever. Of course, we wanted to take the easy way out, and so we started making a lot of videos, a lot of puppet stuff, and animation, and through that, we both became interested in continuing that as a career. So I just started looking at film and television schools and animation schools, and NYU was at the top of the list. I snuck my way in there and was able to spend my college years in New York, which was almost more of an education than actual film school. [laughs]

BTL: Oh, I bet. Were your parents brokenhearted that you didn’t pursue music?

Riege: I think they knew I wasn’t that talented in music. They’re probably both like, how did all of our musical talents translate to two kids who are more visual? I guess they’re related.

BTL: How has music been an influence on you in that way?

Riege: I guess in life, it’s kind of a tone-setter. I love music while I cook and while I work in the shop. I find that a lot of directors, too, when we’re preparing for something, will kind of have a playlist in mind that gives us a tonal reference from an audio standpoint. That’s a big part of it. Of course, it makes such a big difference when you finish a project and when all the elements come together, which I’m not usually privy to. So when I finally see everything come together, it helps so much.

In our first production class at N.Y.U., we were still shooting these silent films, and then, I think it was the third of five that we did in the semester, you were able to add some sound. It was amazing for all of us in the room, for the first time after it had been silent, how much of a difference that made. It can really change the tone of a scene. It’s a huge element. It’s just one of those things I appreciate more as a fan than being capable of creating it, which is a whole other beast.

BTL: I can only imagine The Afterparty music they were playing while you were shooting the film noir sequence.

Riege: Yeah. I mean, just having a reference point for rewatching a lot of genre stuff was a big thing, and of course, then you get the audio planted in your head, even kind of like the hiss and pop and the echo of the dialogue, which was a great touch, I thought, where you feel that spaciness of the microphones that they used to use. It was fun to just be able to completely dive into one world or another.

BTL: Did the worlds ever blend together in an episode between modern times and film genres?

Riege: At times in the morning, you’re shooting in one world with one mindset, and then the next scene is the total opposite, so definitely it is a little bit of a swing back and forth, but very fun. You had to go from modern times to a completely different genre. There’s always the expectation that because we’re going between the present day and our genre stuff, we’re going to be going back and forth a little bit.

I’m not sure how the schedule gets dictated, but [Creator/Showrunner] Chris Miller did the first couple, and he did the noir and the technicolor, which were kind of the two most pushed, I would say. So we dove right into it. We were shooting over the course of those two and a half weeks, or whatever it was, shooting present-day and those two genres, and all of ’em were kind of intermixed. Going from something that’s supposed to feel a little bit more clean and modern and baseline to black and white and then completely over to technicolor, where we’re introducing very deep and specific colors, is definitely an adjustment. Then, of course, the camera crew is like, “Which lens set are we using now? Which diffusion are we using?” It was an adventure and kept things interesting.

BTL: So what about some of those challenges of going back and forth and changing color palettes in the middle of a shoot?

Riege: A lot of it’s just the prep in advance, getting all of our stuff tidied and organized, and then designating, This is what we’re going to use here. This is what we’re going to use there. I had a lot of notes early on as we’re going to catch a few different times where, oops, no, we’re supposed to be in this white balance, so we’re supposed to be shooting at this stop.

Different things that I kind of set as a series of attributes that I kind of assigned to each genre, based on interpreting what I know about them. Then, of course, that’s always a little bit fluid, so we can see how that’s working after we shoot a day or two of material and then say, “You know what? I want to shoot a deeper stop or I want to light this a little bit differently.” So it’s always a little bit of a moving target, like it is on any project, but we went in with a pretty detailed plan in comparison to what I would normally do, which is already detailed, but to be able to switch up between so many different looks is something really unique, special, and fun about the show.

BTL: Did you have very stereotypical tropes for each genre that you had to go by for reference?

Riege: It was an ongoing conversation from the point I first met with Chris and (writer) Anthony King about what genres we’re looking to explore and what these attributes are.What do we all see when we think of a Jane Austen film, a film noir, or a nineties erotic thriller? So that’s where a lot of the reference-watching and cross-referencing takes place. They would say, “Oh, you should check out this film or remember this. I built this kind of living document where I’d pull screen grabs and different descriptions and things and then sit down with Anthony and Chris and say, “Okay, more of this, less of this, this is right on the button”, you know? That way we’re also all able to get on the same page about what is our visual goal and tonal goal going into each of these things so when we’re on set, we’re not spending a bunch of time hemming and hawing about what that is. That’s the one thing that we couldn’t afford to spend the extra time on.

BTL: Did you think of each episode like a mini movie?

Riege: Yeah, I mean, the lighting package would change a little bit. We had our base lighting package, but we would change out what we were using at different times, which of course becomes a management thing when you’re doing pickups three weeks later while you’re shooting a different genre. Sometimes you’ve got to bring gear back.

There’s definitely a lot of that administrative stuff to say, “Okay, we’re back in this world now.” I think it’s easy for people to say, “Okay, well, an actor or a director is going to go down this road and be able to be in this headspace when you’re going from genre to genre,” but it really was the same for my gaffer, my key grip, and my dolly grips, the way the camera’s moving, and the types of instruments we’re using. All of that becomes a method approach to making the material, so you kind of have to live in that headspace.

BTL: If I could just pick your brain a little bit about each style, and you can tell me what were those attributes. Feel free to be a little geeky.

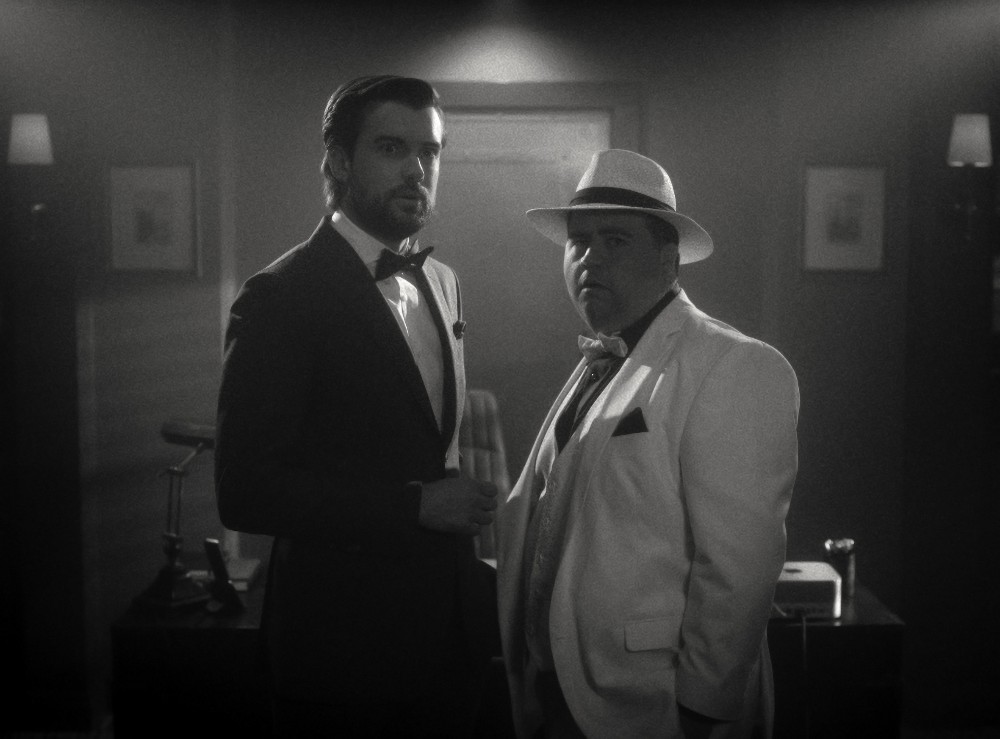

Riege: Sure [laughs]. For the film noir episode, as far as some references that we watched, Casablanca is obviously a big one, as is Double Indemnity. There was this film that I found a bunch of stills from called T-Men, which I thought had a lot of quintessential noir-looking stuff. A lot of it was just getting our edges bright enough so we could get a little bit of a glow. We used a very specific filter package to help with that. We had deeper stops on the camera. The aspect ratio is obviously this kind of 1-3-7 close to square vibe.

We tried to find places where we could implement some kind of trick photography, like mirrors, diopters, and things like that, that seemed to be in vogue. Dutching the camera, and then in talking with Chris, a lot of that traditional way he wanted to design the staging was in a way where it could be presentational for the camera too, where it’s less cutty and more the camera’s in one spot and it moves to the second spot as the actor crosses through and it becomes a new frame. That was another example of moving into a mindset and a way of filmmaking that we’re not always exploring on every show we do.

BTL: What about shooting the Renaissance era and using candles for light?

Riege: You’ve got to have the practicals, of course; the kind of period was daylight pushing, and then the interior was non-electric light. A lot of what we referenced was Joe Wright’s Pride and Prejudice, which was the main reference that we kept going back to on this. There are a bunch of period-type films that I think look great. Emma is one of them; the recent Little Women was good from Greta Gerwig. We used a lot of the golden tones against the cooler blues. A lot of the exteriors should feel very pastoral and sunlit.

In terms of the Pride and Prejudice approach that the Joe Wright film had, they were on these longer-range zooms, so they’re constantly using zooms to make the frames grow subtly. We tried to do that a lot because that was something that we weren’t really doing in any of the other genres. The act of zooming happened because the camera kind of always wanted to be moving in a really subtle and elegant way. The steady cam goes through the dance, and then when people are sitting and talking, a lot of Zoom is used to just grow the drama a little bit.

BTL: How about the technicolor episode? Which tropes did you use for that?

Riege: That follows Isabelle’s [Elizabeth Perkins‘] character, and it’s very Vertigo-like, really Hitchcock-like, technicolor days. A lot of that color palette is in her dress, which was a huge thing. It’s like powder blue, and being able to base off of that There are a lot of color decisions there. There’s this green that we tried to kind of push through the shears of her bedroom. We tried to match as close as possible to the kind of Hitchcock Vertigo green that he used, then tried to mix that dramatic lighting while still having a classic studio vibe to it as well. In a closeup, you might push a little bit more light onto somebody’s face, which almost gives them that glow. So we used filtration here and some older spherical lenses.

Then, of course, the color treatment was probably the trickiest because it’s based on a chemical process that you really can’t properly replicate while shooting. Our colorist, Dave Hussey, did the first season as well, and I’ve worked with him before, and he’s fantastic. One of the first conversations I had with him was, “How do you think we should approach this?” He said, “We’re not the first people to try to replicate this look in something shot digitally.” He’s probably got more experience with it than any of us, and he was just like, “We have to tailor it directly to what we’re shooting versus an end-all-be-all that you just pop in the camera and then spit out technicolor.”

There’s a lot of that emphasizing things with the color of light that we’re hitting things with and then the color of the elements themselves that exist. I’ve always been interested in the idea of taking a digital camera and splitting three sensors in black and white to be sensitive to each of the color channels, and then merging them back together. If you want to get nerdy, a replication of that chemical process where things get separated out and pulled back together would be a fun experiment. Maybe that would be the future option for how to shoot technicolor straight out of the camera. It would definitely take some nerdy exploration [laughs].

BTL: What genre would you say was your least favorite comfort zone?

Riege: The one that was most out of the realm for me was probably the iPhone episode. I’ve done stuff with smaller formats and mixed them in, but I’ve never done it as the primary storytelling device. That was another one where there were a lot of different interpretations of what that meant when we were trying to say that this was shot a certain way. My initial kind of technician standpoint is that anytime we integrate on something like a device, like an iPhone, it still needs to be able to work in a kind of pro-technology pipeline. So we’re often shooting with filmic pro programs that take advantage of the latitude of the sensor to its best ability. But what we found is that when you use that, you also take away some of the elements of shooting on an iPhone that make it so familiar and recognizable to everybody. That is kind of the way the thumb wheel zoom works, and sometimes the exposure will pop and adjust itself.

There are a lot of those things that you start getting away from when we actually use the more sophisticated apps. So we ended up shooting in the native Apple camera app and trying to actually force the camera to do things like jump between lenses, so you’ll see a little pop, and to make it feel very organically shot. You’d think it’d be something you could just hand it to somebody who’s not experienced in camera operation and filmmaking and just be like, “Just follow the scene,” and that would feel natural. But it was also one of the most specifically timed episodes from scene to scene in terms of the way the camera interacts with what’s happening.

There’s a lot of Ken Jeong, the main character, in that genre, and there’s a lot of emotional material in there too. It’s very important that the camera finds him right before or right after a certain line and then leaves him to go catch something or pan across something that we don’t even realize is an important element until people make the connections later. It’s a single camera the whole time. You can’t just throw three iPhones up and shoot it from different angles because it doesn’t feel like you’re having that engagement. That one was probably the biggest learning curve for me, but it was still a lot of fun, and I’m really happy with how it turned out.

BTL: In taking on this project of different film genres, what do you hope that audiences take away when they watch?

Riege: My goal was for people to have fond memories of any of these genres and say, “Oh yeah, I forgot about that little detail that, of course, always happens in this genre.” Just because you’re looking at that, you’re jumping back to the present day, and then you go back to a genre scene, and then the next episode you’re in a totally different genre. So it’s set up wonderfully as a show in that way. I think the other thing is that it would be nice if people watched the show and were like, You know what? I want to go back and watch Body of Evidence now. Maybe as a fringe benefit, if it’s enough to make people excited to go watch stuff that they hadn’t seen in 15, 20, or 30 years, that would probably be great too.

It’s daunting and stressful. It’s a lot easier to generate your own look and generate your own show and say, This is what I’ve authored, versus paying tribute to something that’s already been done in a great way. The primary thing was just the immense responsibility when you’re kind of not copying something but trying to honor something, make it recognizable, and make the viewer make those connections versus force-feeding it to them. If we did that, then I would consider that a success.

Both seasons of The Afterparty can be streamed via Apple TV+.