Marcel the Shell With Shoes On began life as a running joke between filmmaker Dean Fleischer-Camp and his then-wife, actress Jenny Slate, which they turned into an animated short film that became a major YouTube sensation back in 2010.

As the title suggests, Marcel (voiced by Slate) is a shell with shoes who was left behind with his Aunt Connie (voiced by Isabella Rossellini) when his shell family left their home. With the help of a new tenant in the house ( Fleischer-Camp), Marcel goes searching for his family.

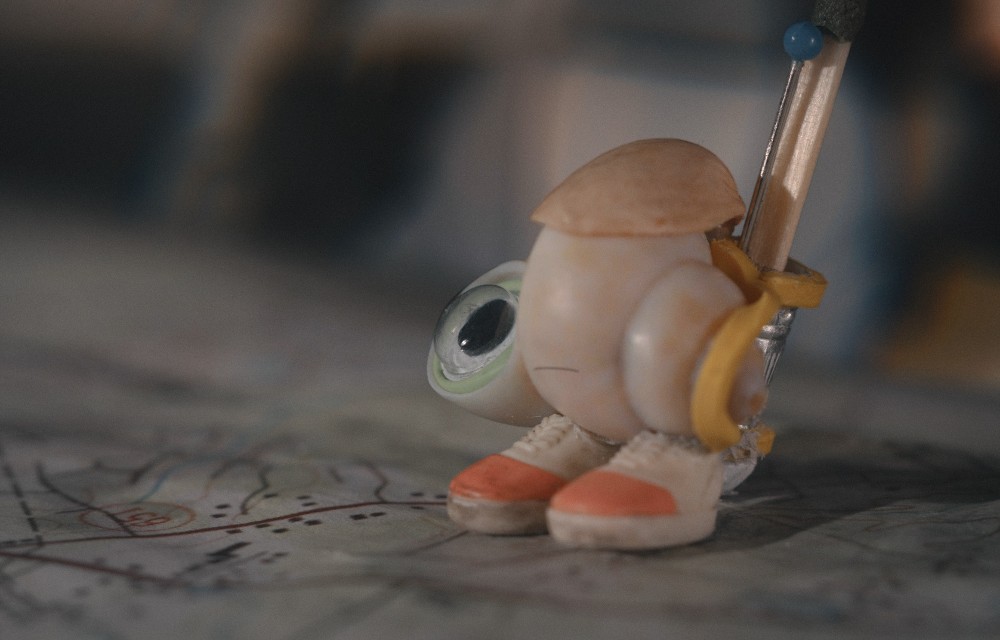

A very rare mix of live action and stop-motion animation, Marcel the Shell With Shoes On took Fleischer-Camp the better part of seven years to complete before it premiered at the Telluride Film Festival in 2021. It was rather unprecedented for the movie to screen at Telluride without any distribution in place, but that began the next wave of Marcel’s journey — being picked up by hot indie distributor A24, which has worked its usual magic in getting the movie in front of discerning audiences.

Below the Line recently had the chance to speak with Fleischer-Camp over Zoom about Marcel’s journey to the big screen, which continues as it expands into more theaters on Friday.

Below the Line: Obviously, you had this running Marcel joke with Jenny Slate, and you turned it into a short you made in 48 hours, so what led you to decide that the shorts were doing well enough to merit an entire feature? How did that transition to the big screen begin?

Dean Fleischer-Camp: I don’t know if [you want] the long version, but when the first short popped off on the internet, we were surprised, obviously, and there was enough buzz around it that we did sort of the water bottle tour of Los Angeles and met with studios. I went to film school, and the goal was always to turn it into a feature, but we very quickly realized, all the combos that we had were about grafting Marcel onto a more familiar tentpole franchise sort of formula. My favorite one was someone suggested that we pair Marcel with John Cena, and they fight crime together. It just was very clear that I, as a very green filmmaker, was not going to be able to adapt it the way that I felt was holistic with what we had created and the character who had become sort of very dear to us. We said ‘no’ to all those offers, and kind of just continued on with doing other projects.

But the character never went away and continued to be this inside joke with me and Jenny. I would say it was like three or four years, we just didn’t pursue anything with the character. But we kept adding to it in our text thread about Marcel and his world, and funny jokes and keeping track of those at some point, I just felt like, ‘It’s actually so rich, that it almost feels bad to keep that to ourselves. Let’s try to actually make that feature now and release all of this great stuff that we’ve built-up over the years, from the confines of our inside jokes.’ That was seven years ago; it took seven years to make the film. That was when I called up Liz Holm, who produced the film, who had produced one of Jenny’s previous movies called Obvious Child. We started pounding the pavement looking for producing partners who could finance it and help us get it made.

BTL: Did you sit down and write a full script from those texts before anything else?

Fleischer-Camp: No. Probably one of the reasons studios didn’t want to work with us was that I was really adamant that we not do that process. I was very aware of the fact that we made that short, totally in the spirit of fun in a very free collaboration where Jenny and I put our heads together and wrote a few one-liners, but the rest, I was just rolling audio, and I was interviewing Jenny as Marcel, and we would say, ‘Oh, that’s funny, but what if we turn this around? And let’s write a joke for that…’ I knew that if we just tried to sit down and write a feature length screenplay, it was not going to be true to the character. I sort of figured out, with the help of our producers, a process that would preserve what was fun about those shorts, this sort of like raw doc authenticity and the rapport between us and the looseness, but also benefit from the orchestration and more calculated storytelling of writing a screenplay.

What we ended up on was that I and Nick Paley, who co-wrote it with us, would write for two or three months, and then, we do two or three days of recording audio with Jenny, and later, with the rest of the cast as we found them. Nick and I both come from editing — we met editing on a television show together — so we would take all that audio and go back into our edit hole and pull out the gems and figure out, ‘Okay, this works better here, or that thing might work for this later scene.’ Then, that would get folded into the screenplay, and we’d write for another two or three months, and then we’d do another recording session. We probably recorded 10 or 12 days total over the course of two and a half or three years, but by the end of that, we had this screenplay that feels like it could have been improvised or a real documentary.

BTL: I didn’t realize that your previous feature was a documentary as well.

Fleischer-Camp: I would consider it an experimental documentary. A lot of people got very mad at some of the documentary festivals that it played at. It was designed to be sort of an intentional statement on how flexible and mutable footage can be and still fall under the documentary [genre]. I found a stranger’s YouTube videos — he had uploaded like 100 hours of home movies with his family. I and a friend of mine edited them to look flawlessly like this family burned their house down to collect the insurance money and then fled to Canada.

BTL: Wow. I have to look out for that one. Many people are interested in the process for this one, so it starts with the voice recording, then editing that together, before you do any of the animation or filming?

Fleischer-Camp: Writing for that three years and recording a couple of days in between, let us end up at the end of that three years with a screenplay, and basically, a finished audio play, almost all the audio with no sound effects or anything. Basically, the story you saw, then we moved into storyboarding. So Kirsten Lepore, our animation director, and I sat down and storyboarded every shot in the movie. And then, we went into live-action production, which is just the empty plates basically, so the entire movie, but without any of the animated characters in the footage. Once we were happy with that cut, we moved into animating Marcel on the stop-motion stages, and then we would marry those two together, the visual effects team and post.

BTL: At Below the Line, we speak to many cinematographers, production designers and costume designers. You have a lot of those same roles in Marcel, but they probably worked in different ways than a normal film shoot or animated film. Can you talk about those differences?

Fleischer-Camp: Totally. I think that it makes for a really great movie, because you can screen that animatic for friends and get feedback, especially working on a tiny, indie budget, make sure that it’s a good story, and everything works before you’re spending money on a shoot. Since you’re writing for Below the Line, this movie I would say was probably more than anything else I’ve worked on such a collaboration between departments, because of the live action, stop-motion mixture. Because stop-motion is such a technical process, it’s basically an entirely different crew that shot each movie. It could only work with tons of hand-holding going on between their counterparts. On the animation stage, they’d say, ‘Hey, what fabric did you use for Connie’s jewelry box bedroom? We’re trying to rebuild that.’ Our production designer in live-action would consult with the production designer in stop-motion, and it really would only have been possible with this very open communication.

BTL: Was all the stop-motion done with backgrounds or was that done on green screen to make it easier to blend it with the live action portion? Or was it a mix of those techniques?

Fleischer-Camp: It was a mix of a lot of different techniques. The most interesting part about the process, and probably the most difficult is that… you know how like any Marvel movie, they shoot the footage and then Spider-Man or whoever is modeled in CG. Imagine that, but instead of the second step where it’s all in the computer, you have another shoot that’s analog, that’s a stop-motion shoot on animation stages, which necessitates recreating the lighting for every shot absolutely perfectly or else it will not actually match with the footage. Our stop-motion cinematographer, Eric Adkins, was on set every day on the live action, taking the most meticulous notes about the lighting setup down to like ‘Marcel standing four inches from a Coca-Cola can and that might bounce light on his back.’

And then, it gets infinitely more complex when Marcel is interacting with stuff in the real world. When he goes out in the car ride, and you see trees flying by and their shadows passing over Marcel, that means for each one of those shadows, Eric and his team on the stages, had to look at the time code, figure out when the tree passed, and then automate a flag to be advanced, like one frame at a time across the light, so the shadow matches up perfectly with the tree we’re passing.

BTL: Some people might watch this and assume it’s all CG, which might have been easier but also may have made the film more expensive. But you still used some computer techniques on the stop-motion side, right?

Fleischer-Camp: There’s a lot of visual effects. I mean, obviously, comping the two phases together was all CG, but there’s a lot of cleaning out rigs and things like that as part of stop-motion that you’d have to do digitally. The bugs also — the ladybug, the beetle, the spiders — they’re all fully CG. I love stop-motion, but what I like about it, I think is what most people probably dislike about it, is that it’s not clean, it’s not polished. It’s a human tactile thing, and so there’s all these mistakes built into it. I think you just get a very emotional performance out of that. Even though CG, you certainly could replicate the look perfectly, you can’t really bake in mistakes that you wouldn’t anticipate.

BTL: I talk to a lot of visual effects guys, and part of their job is to be as perfect as possible and not having any of those things that make people think that it looks weird.

Fleischer-Camp: The entire process of making a fake documentary was all about people being like, ‘But don’t you want it to be perfect?’ and you have to be like, ‘No, I know you’re really good at your job. I need you to do it poorly.’ [laughs]

BTL: That also adds to Marcel’s charm, similar to Wallace and Gromit. It’s interesting that you’re coming out in the middle of summer with Minions on one side and Pixar on the other, and then you have Marcel, which I think is A24’s first PG-rated movie. How was it working with A24? Did they stay pretty hands-off until the marketing?

Fleischer-Camp: We made it independent of A24, and we sold it to them for distribution after Telluride, so they weren’t part of that initial seven years of making the movie, but they’ve done an incredible job of distributing it. Like what you’re saying, it’s harder and harder as a kind of mid-budget movie to bust out or to match the visibility and presence of the studio movies like Minions or Lightyear or one of those, but if anyone could do it, it’s A24. They’ve done an incredible job of really screening it and getting the word out and also doing it kind of holistic with what the character means to people and why we made the movie, which I think is a delicate thing to do with marketing.

BTL: I don’t like getting ahead of a movie before it’s released, but have you consulted with the Animation Guild or the animation chapter of the Academy to see if there’s enough animation in Marcel for it to qualify as an animated movie for awards? There’s always that middle ground where people are unsure whether something should be considered animated or not.

Fleischer-Camp: I know, especially nowadays, where every Marvel movie could be considered animated. It does actually qualify for the Academy Awards under animation, because their rule, I think it’s something like 50% of the main cast. It’s a little bit esoteric, but we fall under that category.

BTL: I want to ask about the music, which is credited to Disasterpeace? Who on earth is that? Is it a man or a woman? I’m not even sure if they’re human.

Fleischer-Camp: What if it’s just an algorithm? We let him name himself. [laughs] No, Disasterpeace, aka Rich Vreeland, is a really incredibly talented composer that I feel so lucky I got to work with on this. He is, I would say, like a virtuoso when it comes to composing music, because he’s had some success with scores before. He did the score for It Follows, a very different esthetic from our score, and he doesn’t like to repeat himself, so I think he could have had a very illustrious career just doing John Carpenter-inspired synth horror scores, but he was like, ‘Well, I did that what’s next?’ Luckily, he had not made a score that was doing the kind of thing that we were doing. I think he just knocked out of the park. A lot of it was inspired by … the brass band song that plays during the credits. He’s a big Danny Elfman fan, so he made this whole brand bass score, so I asked him, ‘Have you ever made a brass band score?’ and he was like, ‘No, just kind of throwing my hat in the ring.’ [He’s a] magician.

Marcel the Shell With Shoes On is now playing in select theaters and will expand into more cities on July 15.