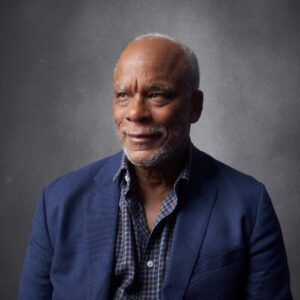

Every once in a while, you have a chance to talk to an absolute filmmaking legend, and that is an apt moniker for documentary filmmaker Stanley Nelson, who has been working in the doc realm since 1989 but who really stepped things up in 2009 with his film Freedom Riders.

In the 11 years since, Nelson has made equally compelling films, such as The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution and Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool. In other words, Nelson has been one of the handful of filmmakers who have addressed and documented some of the most important events in regard to Black history in this country.

Because of that, it made perfect sense for Nelson to tackle Attica, a movie about the famous Attica Correctional Facility in upstate New York where in Sept. 1971, some inmates staged a riot, taking guards hostage with the demand that the prison’s horrid conditions be improved upon. This led to a five-day stand-off where representatives for the prisoners were negotiating with state government officials. Negotiations were making progress when Governor Nelson Rockefeller sent in the State Police who proceeded to bombard the prisoners with tear gas, and started shooting and killing inmates and hostages alike, before taking control.

Nelson’s co-director and co-producer on the film is Traci Curry, clearly an up and coming filmmaker herself, given that Nelson trusted her to share credit on such an important film. Together, they have assembled an amazing array of interviews both with roughly a dozen Attica inmates involved in the revolt, others who were there and reporting on the incident, and even some families of the guards taken hostage. Those interviews are edited together with astounding footage that seems incredible that a.) it exists and b.) the filmmakers were able to find and restore it to create a full picture of the Attica revolt and its aftermath.

Like the best docs, Attica makes you feel as if you were there, and it’s an absolutely shocking and horrifying experience that sticks with you for a long time afterward.

Below the Line got on Zoom with the two filmmakers to talk about Attica, the day after the film’s New York premiere, which took place at the legendary Apollo Theater up in Harlem. Many of the brave surviving inmates of the events at Attica took the stage after the movie, which was a truly inspiring moment.

Below the Line: How did this get started and how long ago? I assume when you did the Black Panthers movie, Stanley, you were aware of what happened at Attica. Was there a particular revelation or aha moment when you realized, “Okay, we have this footage and we should make a movie”?

Stanley Nelson: I wanted to do a film on Attica for probably 20 years. I felt that it was a story that hadn’t been told, and I knew that there was a certain amount of footage that existed, and that there were some people who had survived, and hopefully, we could find and talk to [them]. I think the actual production started three or four years ago probably, when we raised a bit of money and did kind of a teaser sizzle reel, and then kind of went out and started talking to different networks. Showtime bought in, and that’s kind of how the project got started.

BTL: Staci, had you worked with Stanley before? How did you get involved with this as a co-director and co-producer?

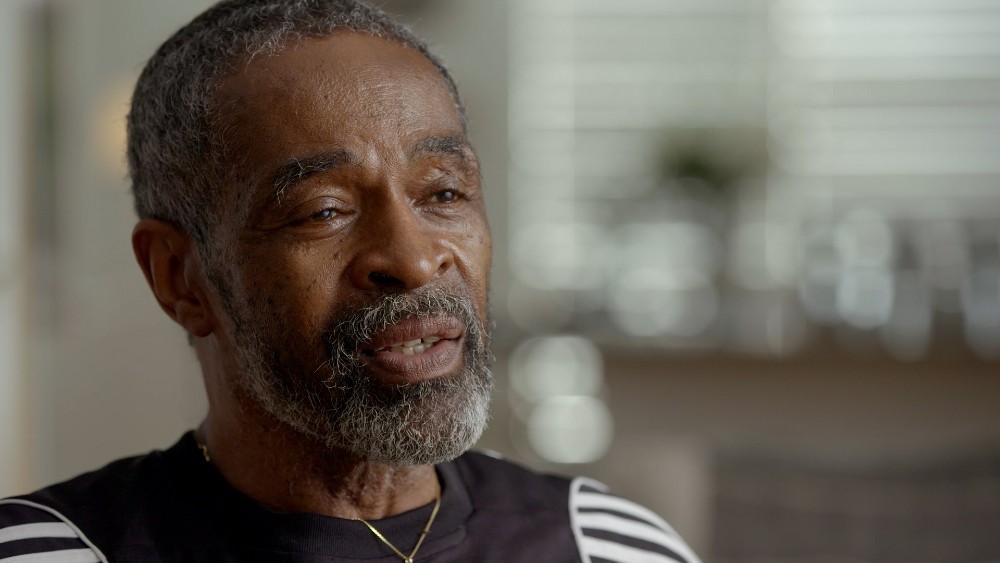

Traci Curry: This is actually the third project that I’ve worked with Stanley on. [We] wrapped the last thing and this is coming up, and Stanley went, “What do you think about Attica?” I didn’t know much about Attica — I hadn’t been born yet. I knew that there had been a prison uprising of some sort. I knew what I think a lot of people knew is that there’s this line from a movie where Attica is sort of a famous thing that gets said. [ED: That would be Dog Day Afternoon.] But generally, I knew that it was something that would involve a lot of questions about justice, the prison system, human rights, abuses of power, and the way that all those things kind of get wrapped up with race and class questions. Those are all things I’m always interested in exploring in whatever ways that I can in the work. It was immediately something that was really interesting and appealing to me to want to dig into.

BTL: I was alive, probably about 6 when it happened, but I think my family wasn’t living in the New York area at that time. But it’s surprising how little most of us know about what happened, a great reason to make the movie right there. Stanley, how much did you know about it yourself before starting to make the movie and before you started doing the research and talking to people?

Nelson: Well, I was alive. I guess I was about 20 years old, and I remember. I didn’t know the details. It was as it unfolds in the film, kind of a daily thing: “All these prisoners have taken the prison. Oh, they’re negotiating. Oh, there’s cameras inside.” And then, when the final retaking, it was kind of like, “Oh, no, no…. ” It was just kind of heartbreaking. I don’t think the details were known. Why did the prisoners take over the prison? I don’t think the details of the takeover were really known, the kind of back scenes of Richard Nixon and Rockefeller.

BTL: In the introduction at last night’s premiere, it was mentioned how timely what happened at Attica was with things that are happening in prisons today. Maybe it’s not as bad, but there are still many problems.

Nelson: I think one of the things that’s really fascinating is that on Monday that lead story in the New York Times was about Riker’s Island and about the horrible conditions on Rikers. People ask all the time, “Did Attica do anything? Did prisons get better or worse?” I think that in some small ways, they’ve gotten better with higher education programs. We also have to take that in context of the fact that now we have 2 million people incarcerated, so it’s gotten a little bit better maybe for the people inside, but there’s a huge amount of people who aren’t out.

BTL: Did you two talk beforehand about what each of your duties would be as co-director, or was it more organic? You mentioned at the premiere that you went up to Attica to do interviews, Traci, so was that by yourself or with Stanley?

Curry: We didn’t do interviews in Attica. We shot a lot of the aerial footage of the prison, outside of Attica. Because of the pandemic, a lot of the interviews had to happen remotely, and then the ones that we did in person, we either went to where people were or brought them in to us to do those interviews. We didn’t actually interview anybody in the village of Attica.

BTL: The movie looks great, including the interviews, so did you send the subjects cameras and have your cinematographer work with them to make it look so good?

Curry: One of the things that Stanley talks about a lot, so he might want to talk a little bit more about that. I was here, but we sort of didn’t do the thing where you kind of trust people to do their own camera work, because we wanted the quality of the interviews to be as high as possible, and you just can’t get that when you rely on people to film themselves. [laughs]

Nelson: We said it from the very beginning that we want to try to make this film look like it’s not shot in the time for COVID, so we didn’t want people wearing masks. We didn’t want to send a camera kit to people where they set up a little camera and a ring light, because it looks okay, but it doesn’t look like the film could have been. I think Tracy’s being pretty modest. I mean, she did all the interviews for the film. I mean, it’s just incredible. When I look at the film, it just looks like it was shot three years ago, before COVID. It just looks beautiful, and the kind of rapport people have in the interviews is not something that you can see, but sometimes, if Tracy’s not in the room, the camera was always in the room, the lighting set-up. That’s really what we wanted, because we call these kinds of historical documentaries “evergreen.” This film will be just as valuable, hopefully, five years, 10 years, 15 years down the line. We didn’t want people to be like, “Why does it look so crappy?” We really wanted it to really get the look of photographs. I just love the way the film looks. Another filmmaker came to me last night after the screening and asked, “Oh, my God! What camera did you shoot with? Who did you use to shoot cameras?” And I was like, “We used every camera in the book, and I think there’s almost ten different people listed as cinematographers.” We shot in a time of COVID, and it’s just not simple. Everything becomes more difficult.

BTL: Obviously, this incident happened 50 years ago, so most of the inmates had to be in their 70s or older now. Did you find that everyone you talked could remember what happened and how they felt 50 years ago? I assume you found many of the inmates through the settlement they got from the state?

Nelson: Tracy can answer that, because she found the people, but I just want to say, because I’ve done a number of historical films, 50 years is not that long. 70 years, I guess, is a problem, but we knew that a lot of the inmates were young. They were 20 to 25, so 50 years, that’s 70 to 75. I went into it thinking that the people that were in the Nixon administration, and the observers, I felt, would be a little bit harder, because they would be older, but Tracy can tell you the details about finding them.

Curry: The answer is every which way that we could. My goal was to find every single surviving person who was there and put them in this film. That was the intention we set out with, but yeah, we had a great head start with a couple of the consultants on the film that you see in the credits. Heather Thompson, who wrote the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, and Judith Clark, who is a prison activist, pointed us in the right direction initially with some of these folks. And then, it was just kind of asking and asking and asking again. Some of it was going through those court records for those names. Some of it was looking through public records and just kind of cold calling and contacting people. Some of it was every time you find someone, you ask them if they know somebody else. We were lucky in the sense that so many of the prisoners were young men at the time — the observers, however, were not. We have a couple of nonagenarians like Clarence Jones said that he turned 90 this year. Herman Schwartz is over ninety. There was a question of will we be able to find those people? And quite frankly, if we find them, how clear will their recollection be? We really lucked up, that we found these folks that, at 90, still have the same memory that they did 50 years ago and were able to offer a such a clear recollection. I’ll also say that there is this thing about Attica, and the people who touched it, and who it touched, where it just burrows into their psyche, in a way that really does not allow anybody to ever forget it. I always go back to this thing that Malcolm Bell — who’s one of the Attica prosecutors who tried to prosecute police in the aftermath — writes in his book that Attica has a way of holding people. I have found that everybody from the prisoners, to the families, to the lawyers who do this work to the observers, to anyone that’s ever done anything around Attica, the people that have written the books, that is absolutely true. There’s just something about this experience and what happened and the brutality of it. I think the shock that the state would do this to American people, all of that just kind of stays with people in a way that you don’t really have to dig too deeply before it all kind of comes bubbling back up to the surface.

BTL: One thing that’s really stuck with me from watching the film is that those inmates who survived that experience, they’re still in Attica on Tuesday and Wednesday for however many years. Eventually, they might have to go back to that D-yard where so many were murdered and degraded. It shows amazing strength and bravery that they could survive the psychological experience on top of the physical one. Did you talk to any of them about that aspect of their experience, or was it too difficult?

Curry: The brutality continued, but at some point, we get the point, right? They were brutalized, but that night, they’re back in their cells. For many of them, the stigma of having been one of the Attica prisoners who were in D-yard, because remember, it wasn’t the whole prison or all the prisoners. It was just this group of prisoners that ended up in D-yard. It kind of follows them throughout their time in the prison system. For some of them, it causes issues with parole, years and years later. It’s certainly something that stayed with them, psychologically, but also just in terms of the way the state viewed them and dealt with them in the system.

Nelson: One of the things that’s really amazing that you will try to wrap your head around, I was talking to Tyrone Larkins [another Attica inmate] the other day, and I think he served 23 more years at Attica.

Curry: It came up in one of his parole hearings 20 years later. It came up that, “Weren’t you involved in that rebellion?” And he’s like, “What does this have to do with the decision about whether or not I still need to stay in this prison 20 years after it happened?”

BTL: You have a lot of great interviews, and I’m sure that this could have been a five or six-hour miniseries, but did you want to talk to any of the families of the inmates who were killed that day? Was that something you looked into, or did you feel that took a tangent from what you were trying to achieve with the film?

Nelson: I’ll let Traci answer most of this, but we did interview LD Barkley’s sister, and it just felt in some ways like it was too far removed from the story. The story is so immediate, it’s so much told by the people who were there and affected by it, that it just seemed a little bit removed. In the same way, we were going to interview historians for the film. Heather Thompson, who wrote the book and was an advisor on the film, and we actually interviewed one historian and we put him into the first assembly, and he just seemed like he was talking from another world. To cut from him to Akeel or Shariff or cut to Al Victory, it just was really strained, and we realized that we didn’t need that, that we didn’t need historians. I had the hard job of calling up Heather and saying, “We actually don’t really need to interview you.” But she was great, and she said, “If you don’t need me and the historians, and these guys are telling their own story, then that’s perfect.”

Curry: Like Stanley said, we did interview Tracy Barkley, LD’s sister, and she’s great. I think you go out and get as much as you can and find as many people as you can, and then you come back and in some ways, the substance starts to sort of dictate the style. In that moment, I think there is a temptation to want to know more about LD, and there’s a whole tangent that you could go off ’cause this young man speaks so compellingly in the yard. You hear someone saying he was gonna get out in a few weeks. He was there on a parole violation and probably shouldn’t have been there in the first place. There’s a whole story you want to hear about, like who is this guy? But then, at some point, it’s like, “What is the story that we’re telling here?” That’s just sort of one of those difficult decisions that you have to make in the service of telling the best, most compelling, and incisive story that you possibly can. Certainly, I had conversations with family members of some of the prisoners. Ultimately, we just figured out that wasn’t the direction that we’re going to go in, because we wanted to keep it so much in the moment of the people who were there in the prison, in the town outside the prison. It starts to just get a little unwieldy if you go too far afield from that.

BTL: Let’s talk about the footage and how you and your archivists found all of it. There were things that were shot for television, but there weren’t television cameras still inside when the state police started their attack to take back the prison, was there? So where did all that shocking footage come from?

Nelson: I’ll let Tracy talk about the ins and outs of it, but that was New York State surveillance, and they were up in the tower shooting with what’s called a PortaPack, which was the iteration of home video. You had a camera, which would only shoot black and white, and it was connected by a cord to a huge tape recorder that you would have a strap on it, so you could physically carry it around. And it was reel to reel. They were up in the tower, shooting video the whole time and you actually hear their audio, because they left the mic open. I guess they didn’t know how to take the mic off, so they were constantly talking through it, and that was the black and white footage of the takeover. Tracy?

Curry: You see in the coda at the end of the film that in 2000, there was finally this settlement, where the prisoners get $12 million and the families essentially shamed the state of New York into giving them an equivalent amount of money. That was 2000, so that’s 30 years of litigation, and legal cases in and out of the courtrooms that happened between 1971, and when that settlement happened. So, all of that stuff is a matter of public record, because it’s evidence in a lot of these trials. We were able to get the archive of a woman named Liz Fink, who was really dogged and determined in pursuit of justice for the prisoners, along with a team of people, including Frank “Big Black” Smith, who you see in the film and now became a paralegal. We were able to get access to her archives, which included the evidence of what had happened in D-yard on the 13th, so that’s all the photos of the bodies. There was some of the surveillance footage in that, and everything that they were able to access, we were able to access and include in the film.

BTL: I’m amazed that the physical media with the footage actually lasted for 50 years, knowing how flimsy the tape must have been in those early recorders.

Nelson: One of the great things is that they transferred it again and again. They transferred it once and then they transferred it again. We’re not going back to the original reel to reel PortaPack tapes. I would guess that those were in really, really bad condition, but we did go back to the original 16mm, wherever the networks still had it. That’s why some of the footage just looks so incredible, because the networks would send us screeners that they had copied it all onto tape. Then we went back and said, “Do you have 16 millimeter of this? Do you have the original 16?” In many cases, they did, so they retransferred it for us from the original 16, which was an extra added degree of difficulty, because they had to go back to the original 16, they were short-staffed. We were asking for it in June, and they were like, “Well, we can give it to you in October.” We were like, “You gotta do better than that.” And they said, “Okay, August.” “Can you do a little bit better?” That’s why some of that footage looks so good, and then, look, the stuff that was shot on PortaPack, the New York State surveillance, I mean, at some point, the footage is so incredible and so dramatic that your mind excuses the difficulty with how it looks.

BTL: My last question is how did you find the taped recording of the phone call between Nelson Rockefeller and Richard Nixon, because that’s pretty damning. It’s surprising that phone calls were being recorded and that whoever did tape it would release it or make it known that it exists.

Curry: I wish Rosemary [Rotondi, the film’s archivist and researcher] was on this call, and she could probably give a better answer, but I want to say either the Rockefeller or the Nixon library had those tapes. It was just a matter of knowing the right people to ask, and then digging through all the files to find this date and this time. We sort of knew around the time and date when that would have happened, and then just kind of going through it all to find these little snippets of it. Again, we had a lot of support and guidance from Heather Thompson, who is the historical advisor on the film, so she offered some input about that as well.

Nelson: I think the Nixon library has those tapes. I think that Nixon was so focused on erasing the Watergate tapes that he kind of forgot to erase those tapes.

Curry: Also, Nixon wouldn’t have seen that as something shameful that he would have wanted gotten rid of, so they probably were just kind of in there along with all the other things he said on the phone to people.

Nelson: It’s shocking, but in Freedom Summer, we have a tape of Lyndon Johnson talking on the phone about “negroes.” I mean, that’s the country we live in.

Attica is now playing in select theaters across the country and will premiere on Showtime and Showtime On Demand starting Saturday, November 6.