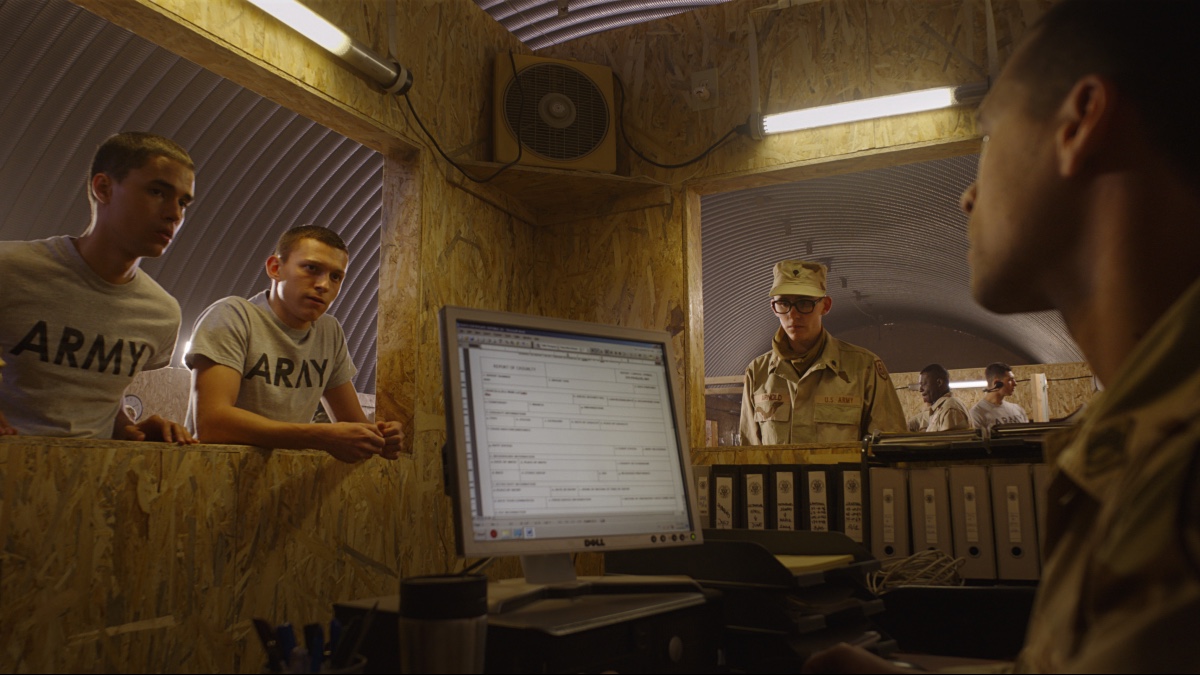

An Army medic struggles with PTSD and opioid addiction in Cherry, the latest film from the directing team of Anthony and Joe Russo. Adapted from the novel by Nico Walker, it stars Tom Holland as the eponymous Cherry, a vet-turned-bank-robber struggling to free himself and his girlfriend Emily (Ciara Bravo) from drug dependency.

Starting in Cleveland, the story shifts among several time frames, from college to basic training to the Iraq War and back. Cherry narrates his life in both the past and the present, at times breaking the fourth wall to address viewers directly. Characters and incidents can spur separate scenes, play out in alternate versions, and return at different points in the film. Keeping track of the narrative was Editor Jeff Groth, ACE.

Below the Line: When did you get involved with the project?

Jeff Groth: I would say about three months before shooting started, while I was finishing up Joker. I had worked with the Russos on Community and sent them a message that I was interested, that I didn’t even need to know what it was about. I started about a week after finishing the final checks on Joker.

BTL: The size and scope of the film must have been daunting.

Groth: I wasn’t really concerned about that. If there’s anything daunting about the film, it’s that they were trying to make an epic on a limited budget.

The main challenge for me was to honor Tom’s performance. He’s got to show a long piece of time in a person’s life. If you’re shooting something from the fifth part of the film in the first week of production, as an actor he’s got to bring in experiences he hasn’t had yet, show the viewer how this person got here and what he’s capable of. And he’s just starting out, he hasn’t gone through the movie yet.

BTL: Cherry includes voice-overs, jump cuts, stream-of-consciousness sequences, elisions, different points of view.

Groth: All those things kind of go together, and the points of view really end up being one point of view, that of Cherry. The differences refer to the “when” of Cherry, not the “who.”

I always looked at it as if Cherry imagined a movie about his life in his head. This is the movie that would be, that’s the unifying consistency.

Beyond that, shifting points of view depends on when you are with him. When he’s speaking in a voice-over he’s speaking in the past. When he’s speaking directly to you, when he’s speaking to the camera, he’s also essentially speaking in the past, even though it’s a different kind of trick.

Those shifts were largely built into the filming. Take the very first scene in the bank, when he starts talking to the camera. He’s sliding 15 years into the future in his performance, he’s able to speak to you from that distance and then going right back into the moment. That’s all on camera, that’s not anything that I’m doing.

BTL: Can you talk about how you collaborate with the Russos? For example, are the point-of-view shifts in the script? Are they in the coverage? Do they evolve as you’re working?

Groth: They evolve. Certainly the voice-over, some of it lives as written, some of it was adjusted. Initially there was more in there. I feel like there’s always a battle when you’re using voice-over. How much do you really need to say? Does it become too talky? Can you take those pieces and distill them down into their most important parts, or remove them altogether?

But the voice-over was always in the script. Some pieces were even timed. Pieces of it are working in tandem with shots to make jokes, for example.

The jump cuts, the shifting of time and perspective that we did in the editing — the Russos encouraged me to go for it. One of my goals in editing is to surprise directors with what they’ve shot. In a good way. I’m hoping to show them that they got more than they thought they did. I’m hoping to pull out more, make more of what’s there.

There are instances where Cherry will remember things in a certain way, or the scene goes by and then you get another piece of information in the very next one. In the individual beats the story is not always completely linear, even though overall it’s extremely linear.

BTL: How comfortable are you discarding footage?

Groth: The Russos gave me free rein to do whatever I saw fit with the material they shot. The beautiful thing about editing in the 21st century is that nothing is destructive. As long as you don’t delete your files you don’t lose anything. The Russos always had the option to say no, let’s go back to the drawing board on this.

During production they want to see things in a very rough form as quickly as I’ve assembled them. Because they’re evaluating, okay, what do we have here, is there anything more that we want to get. Not so much in terms of a reshoot, but in terms of is there anything we can sneak into a day, a few shots or a small scene here or there that’s going to give us more options when we’re done shooting. Because we were never going to reshoot with this.

BTL: How much did the Russos participate in the editing?

Groth: They’re in the editing room all the time if they can be. On Cherry we finished shooting a couple of weeks before we ended up going home into lockdown.

But we did a significant amount of work before that. A lot of what you would find being done in the director’s cut we were doing during production. In addition to cutting new scenes, I’m refining scenes, experimenting, trying things. We got to the point where they didn’t necessarily have to be in all the time, they would give me an idea of what they were going for. They were extremely collaborative, they really gave me a field to run with.

BTL: How do you edit the elaborate crane and Steadicam shots in Cherry?

Groth: I don’t feel I’m locked in to keeping them because I’ve established enough jump cutting in the movie. That’s one of the reasons why I use do jump cuts, I want to show you the next thing I think you should see. Even if they spent half a day to get a shot on a crane, if it’s appropriate to cut into it, I’ll cut it. I try not to visit set too much because I don’t want to know all the work that’s gone into these shots. And I don’t want to offend somebody by cutting out a half-day of work. But in the end I have to deal with the viewer, and if the viewer isn’t going to like it, it’s my job to get rid of it. Even if it’s just three seconds in the middle of a long take. You know what? I’d rather jump cut here than live with these three seconds that shouldn’t be here.

One of my favorite parts in the war section is when Cherry’s laying on his bunk talking to Jimenez [played by Jeff Wahlberg]. It’s one of the few times he’s laughing and smiling in the movie, it’s almost his happiest. And then with each cut it gets more and more serious and sad and less happy to the point where you’ve gone in the space of four cuts from laughing and joking to saying very seriously, “I hate it here.”

BTL: Do you ever worry about cutting too far ahead of viewers?

Groth: I try never to underestimate the audience. I’m also trying to create more of a feeling than a specific set of information to get across. If a shot will make you feel a certain way, whether or not you understand its positioning, then it’s still appropriate.

A set of cuts I particularly love is in the home section, when he goes to visit Thomas Lennon, who plays the VA doctor who prescribes Oxycontin for him. There are a couple of cuts in there that are extremely fast. It’s within the context of the conversation, but they’re meant to throw you off balance, the same way Cherry feels off balance. Again, as always from his perspective, but giving you the feeling of things kind of popping in a way that they shouldn’t.

BTL: Was it a problem finding a consistent style with all of the different film stocks and aspect ratios the Russos employed?

Groth: I’m looking more towards big screen versus small screen. I’m generally looking to play things for a theater environment first and foremost. Something that plays in a theater environment will play in a smaller screen as well.

One of the things about working for the big screen is you have to figure out how viewers’ eyes get across the screen. With a reduced aspect ratio, you don’t have to worry so much about cutting from action on the right side to action on the left side and giving whiplash to the people sitting in the front row.

Also, where is your eye landing on the space between cuts? With a smaller aspect ratio it’s easier to hit that mark.

Very wide shots can get lost on a computer screen or iPhone. It’s never going to be as grand as being in a theater on 70mm. Right now, I’m one of the few people who have seen Cherry in a theater. It’s really great. The sound effects are incredible in Atmos and the color, the framing on the big screen are quite beautiful.

BTL: Cherry opens with a montage of Cleveland. Can you talk about putting that together?

Groth: That montage was very much meant to establish a sense of place. The book takes place in Cleveland, the movie takes place in Cleveland, Joe and Anthony are from Cleveland, I’m also from Cleveland. I think we all wanted to make it feel that it wasn’t just Cherry moving from one place to another, but also reflecting on the place where he’s grown up and lived.

That montage operates through that lens: how do you make it feel like Cherry’s Cleveland? He sees images of urban decay, but they are also beautiful images of urban decay. It’s not done to slight Cleveland, it’s done with a sort of reverence. Or at least that’s how I saw it.

The pressure was that we had way too many shots. The montage was three times as long when we started out. And the sequence can’t be that long, there’s no reason to spend that much time there.

So there is the pressure of taking out these great shots, and likely never seeing them again, and living with what you have left. My process beyond that is to watch it over and over, as much as I can, and find things that I think on the fiftieth viewing annoy me. I’ll take that out. What you’re ultimately left with there is something that you feel will stand the test of time.

Cherry is still playing in select theaters and will be available to stream on Apple TV+ on Friday, March 12. Also check out our interview with the film’s DP, Newton Thomas Sigel.

All photos courtesy of Apple Originals.