A lone scientist isolated in a polar outpost tries to warn astronauts returning from a space mission that an environmental disaster has swept over the planet in The Midnight Sky. Directed by and starring George Clooney, the movie is currently streaming on Netflix.

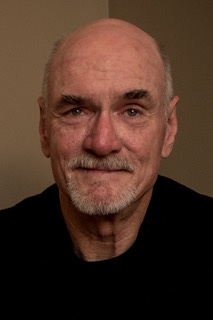

To make The Midnight Sky, Clooney assembled a crew of distinguished veterans, like Production Designer Jim Bissell. This is their sixth collaboration, including the award-winning Good Night, and Good Luck. Bissell also worked with Steven Spielberg on the landmark E.T.—The Extraterrestrial, as well as with distinguished directors like John Schlesinger and Ridley Scott. In 2015, he received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Art Directors Guild (ADG).

Below the Line spoke with Bissell by telephone.

Below the Line: When did you join the project?

Jim Bissell: I started in early April 2018, and we started shooting in October. The script was pretty much completed, although George always tweaks it. That’s what’s fun about working with George. He has a very solid idea of what he wants to do with the material, but then the final stages of it are very collaborative.

BTL: Can you describe your process of working with Mr. Clooney and the other heads of department?

Bissell: With George, you ask, “What are your ideas on this? What do you want to see here? How do we want to move the camera?” We start playing with those ideas.

That started within my first two or three weeks. George worked with a storyboard artist named Dan Sweetman here in the States, getting his ideas out so we could all react to them, including Martin [Cinematographer Martin Ruhe] and Matt [Kasmir, Visual Effects Supervisor]. Everybody comes up with ideas, pitches different approaches, George thinks about them, and then we start really honing in on what’s going to be shot on location, what’s going to be shot on stage, what those stage sets have to look like, and how many different iterations of those sets do we have to build to get the shots we need.

Our department is at the forefront of instigating the construction process and moving it along as quickly as possible so that we’re not spending huge amounts of time and overtime building stuff. I start looking for research as well as the kind of locations that we can sort of tie into sets. We then look at the techniques we will need to use to do both of those. How are we going to light them, blend them all together to make them look like they’re all shot in one space over the course of the night?

As you consider each technique, and the images you want for each sequence become more obvious, then you bring in the people who specialize in those sorts of things. When George’s character takes refuge in a building that starts to sink, you need the physical effects people. They are going to build the hydraulic works that flip big ice sheets around, and the kind of gimbaling we’re going to need for the interior space as he wakes up and sees the thing collapsing.

BTL: How would you describe your personal approach or philosophy to your work?

Bissell: I try to take in as much as I can, all the disparate information you have to have in order to achieve a dramatic design. By that, I mean you do detailed structural analysis of the film, you look at the thematic material that you want to embrace, you look at actual research, what is going on realistically with the sets and environments you’re trying to create and what kind of dramatic image you’re aiming for?

Because ultimately, movies are a series of images that tell a story. The primary components of movies are performance and context. I think all of us who are below the line deal primarily with context. Whether it’s makeup, hair, costume, dramatic environments, and so on. I try to look at all of these elements and then put them together so that I know how much time we have to execute any design ideas that get generated. And that there’s a consistency in look.

BTL: The Midnight Sky takes place on earth and in outer space. How would you describe its “consistency in look”?

Bissell: It was about trying to create something that was slightly detached, slightly in the future, but very plausible. We always saw it as about 30 years in the future.

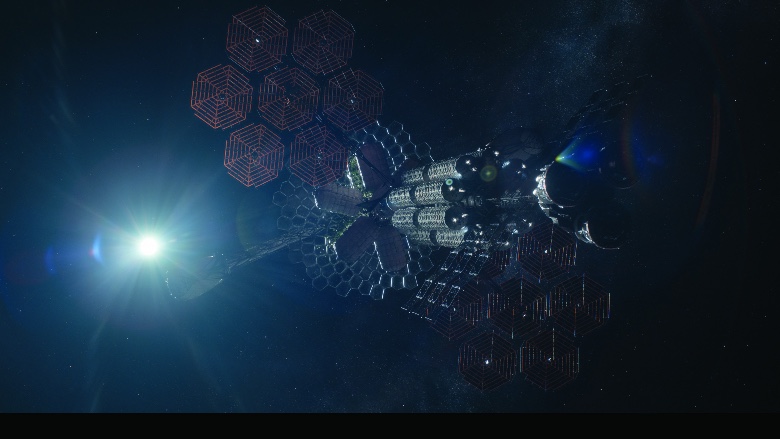

BTL: How did that translate into designing the Aether space probe?

Bissell: What would make the audience feel like we are in the future, but still recognize what we are seeing? We don’t have space probes yet, but we have the ISS [International Space Station], and the two big problems for astronauts on the ISS are weightlessness and radiation.

I looked at what’s being done right now with inflatable habitats. With those, you could address weightlessness with centrifugal force. There’s nothing else out there that is even remotely feasible to simulate gravity in deep space. We went with a baton design that creates smaller units at each end where the centrifugal force would function. And we imagined layers of lightweight material to protect against radiation.

So we have an exoskeleton that contains the units to prevent them from flying off into space as they spin around. And an endoskeleton that attaches to the pivot point and holds the floors in place.

There’s engineering technique called topological optimization. You use supercomputers to evaluate complex engineering problems, and it comes up with exactly the structure needed to perform under the circumstances described.

Topologically optimized objects have this incredible organic look, so our exoskeleton looks almost like the rigging of a clipper ship designed by Gaudi. And it’s feasible — the technologies are pretty much in development right now.

BTL: And that design technology is reflected in the locations on Earth as well?

Bissell: Exactly. You probably noticed that in the structural roof supports in the Barbeau Observatory. It’s all topologically optimized. It’s as if that kind of construction technique became more prominent as a manufacturing technique in the future, because it uses material so efficiently.

BTL: The Barbeau is unique.

Bissell: We wanted it to look cold and foreboding, and also relatively new. The bottom line is you would not build a telescope in the Arctic, you wouldn’t open a mirror that size in those conditions. But in an odd way, that’s where you get into dramatic imagery. When you look at the profile of the Barbeau, it looks like a head, like somebody’s brain. And that’s it, you’re crawling inside his brain, getting in his head, his life.

BTL: Is that what you and Mr. Clooney agreed on originally?

Bissell: It evolved. My first stab was far more of a hodgepodge, like a contemporary version of the complex in The Thing: modular units a bit like shipping containers just sort of thrown together because they suddenly had to have a base up there.

George didn’t like it all that much, he wanted a more futuristic feel. So I looked at designs evolving in the Antarctic. Then I took the idea that this space represents what Augustine [the name of Clooney’s character] is all about, and that would be a telescope. I put in a large concrete base and an enclosure and started realizing, well, that’s his head. That’s where all the data gets processed, that’s where his observations are, that’s his life.

BTL: Mr. Clooney has spoken about having to shift some exterior shots from Iceland to soundstages at Shepperton. Did that affect your work?

Bissell: It was always planned as a combination of exterior sets in Iceland and interior sets. It’s just that the proportion shifted. We didn’t get as much as we thought we were going to get in Iceland. The wind was blowing too much, and there wasn’t enough time, but Martin told George that they could match this environment on stage.

BTL: How big a project was this overall?

Bissell: It’s tough to say. So much was in flex, and we were shooting in three different locations. At one point we had a crew in Iceland building the entrance to the Barbeau, the antenna platform, the wrecked aircraft and the pod we talked about which was actually on a glacier. Concurrently, we had all the big sets being constructed at Shepperton. Also a smaller crew down in the Canary Islands for what later became the K-23, the Jupiter satellite.

BTL: Such a large-scale film deserves to be seen on a big screen.

Bissell: It was designed and built to be seen on IMAX. I have not seen it in a theater, and I’m itching to.

BTL: Are you comfortable working with Covid-19 production protocols?

Bissell: I think they work, but the biggest problem we’re discovering is not so much staying healthy and protecting against Covid and adhering rigidly to protocols. The biggest problem is safety on the set, especially in construction. Somebody has a construction accident, gets cut with a saw or whatever, there’s no room in the emergency rooms to treat them. That’s what concerns me the most. You can’t do stunt scenes because if anything goes wrong, where do you bring an injured crew member?

That’s the real hazard. We just have to wait until the hospitals are less full before we can go back to shooting.

The Midnight Sky is now on Netflix.

All pictures courtesy of Netflix, except where noted.