When it comes to documentary filmmaking, director Brett Morgen continues to be one of the more interesting filmmakers working in the format. His 2002 film The Kid Stays in the Picture (co-directed with Nanette Burstein) introduced millions to studio exec Robert Evans, who (among other things) was responsible for bringing Mario Puzo’s The Godfather to the big screen. 2007’s Chicago 10, which kicked off Sundance that year, recreated the famed trial of persecuted political activists using animation, while 2015’s Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck and 2017’s Jane were innovative portraits of complex people that used existing audio recordings (in the case of the former) and archive film (for the latter).

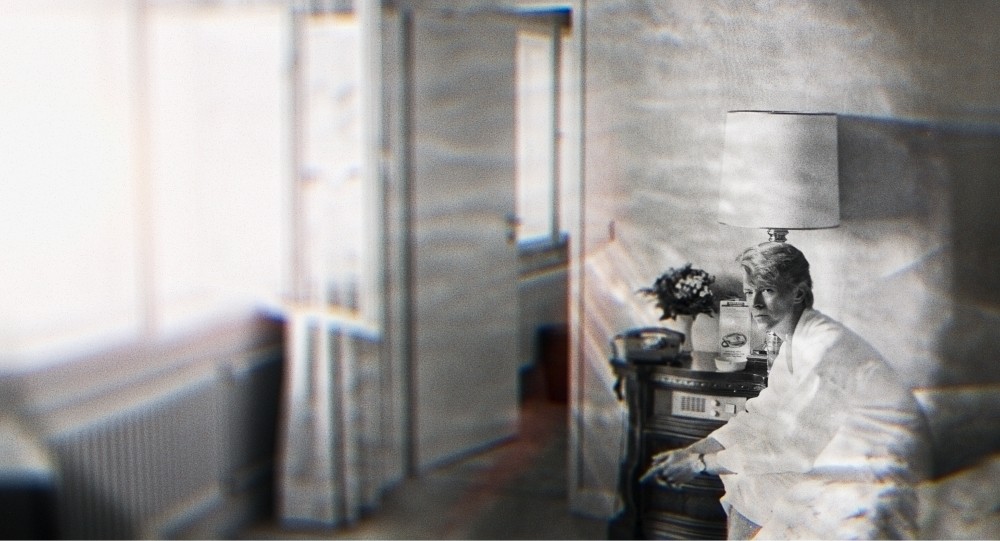

All of those films helped pave the way for Morgen to direct Moonage Daydream, his avant-garde exploration of the life and music of the late David Bowie. The immersive documentary blends existing footage from various sources, including concerts and television interviews, to create a film as experimental as Montage of Heck but one that ends up having far more mainstream appeal, mostly due to the vast reach of Bowie’s music.

In fact, Moonage Daydream is such an immersive experience that it debuted in IMAX theaters a few weeks back, becoming the first documentary in almost nine years to open in the top 10 at the domestic box office. Seeing the movie in a theater really helps to enhance the music and the visuals Morgen assembled as the film’s sole editor. Of course, he had a number of talented collaborators, including original Bowie producer Tony Visconti as the film’s music producer, Re-Recording Mixers David Giammarco and Paul Massey, Supervising Sound and Music Editor John Warhurst, and Supervising Sound Editor Nina Hartstone.

As Below the Line discovered when we recently hopped on Zoom with Morgen, he may have (at least tangentially) been inspired by those planetarium laser shows that some of us older folks may remember from our youth.

Below the Line: I know you’ve been working on this film for five years, so how did the whole thing begin? Who reached out to whom to get the ball rolling here?

Brett Morgen: It started with a desire I had to take over the IMAX science museums at night. I noticed that they closed their program down at six o’clock in most of their science halls, and I had this idea that IMAX has the best sound system on Earth and the biggest screens on Earth. I was like, ‘Well, there’s this valuable real estate that could potentially be used for something other than a linear narrative film.’ Maybe, because they were science museums, I was thinking, like, a planetarium, [and] I had this fantasy — What if you can do these 40-minute, immersive music experiences that aren’t based on an artist’s biography or facts or [a] list of colleagues and collaborators, but just a purely immersive experience that would potentially invite the audience to have a sublime and intimate encounter with an artist that they love? In concept, it was like, ‘Oh, we’ll do a six o’clock Beatles, seven o’clock Hendrix, eight o’clock Jay Z, nine o’clock Brandi Carlyle.’

I met with Greg Foster, who was running IMAX at the time — he seemed into the idea. I presented it to a friend of mine at a finance company — they agreed to finance a slate of 15 of these, and then shortly around that time, David Bowie passed away. I had met with Bowie in 2007, so I knew his executor, who had been in our original meeting, [and] I told him what I was interested in doing, and basically, he said that it seemed like something they might be interested in participating in. The timing at [that] point was too close to his passing, so I was told, ‘Give us a call back later in the year,’ and I did, and we embarked on this journey [together].

BTL: I know you had Kurt Cobain’s recordings to use as the basis for Montage of Heck, but what was your first step in this process? Bowie had been on television and in films for many decades, so I know there was a ton of stuff to work from, but how did you decide where to begin?

Morgen: There’s a lot post-1980, but in the ’70s, there really isn’t that much material to plow through. I always start chronologically, to see what sort of throughlines emerge organically. In the case of Bowie, he was able to provide me with a throughline related to transients that was both applicable [to] his art, as well as the way he lived his life, which is a rare kind of fusion where you have an artist whose creative approach mirrors how they live their life. It suited itself well for the non-biographical adventure that I was hoping to pursue.

It’s important to identify non-biographical versus non-narrative. It’s an area of narrative that’s very much designed like a Greek hero’s tale, where David goes on a series of adventures; he sort of creates his own challenges for himself. He makes things as difficult as he can for himself, not so he can gain the wisdom to become a Jedi knight, but so he can just live to the next day in the best way possible.

BTL: Although you approach your research chronologically, you didn’t present his material or his career that way. For instance, there are songs from later in his career that show up early in the movie and vice versa.

Morgen: The film takes us from the moment David was introduced to the public as Ziggy, as this amalgamation, and sort of goes through how he created his arc, which was by putting himself into the fire, until he no longer needed to put himself in the fire, and that’s the narrative of the film. When he meets [his wife] Iman, he arrives at a place where he no longer had to be nomadic, but he could still create art.

I think there was a misconception, perhaps, slightly, around the film — because the discography post-’95 isn’t used as much — that it was some sort of editorial choice in terms of having some sort of preference towards his earlier work. Nothing could be further from the truth — I prefer the latter work. It’s just when you’re telling a story, this story tells you when to get out of the car, and when to get in.

BTL: I’m glad you mentioned how the IMAX experience inspired you to make this movie, because when I saw it in IMAX — sitting fairly close to the screen — I quickly got the feeling that you were trying to instill.

Morgen: It’s so interesting for me, personally, because I think of everything up to the first screening as an audition. When you’re off-lining a film — especially a film like this — the form is as much the serving as the content. I can’t see what the form is until we’ve completed our color work and we’ve completed all the sound work. I started this thing in 2016. It wasn’t until, let’s say, April of 2022 that I had the first opportunity to view what this was designed to be.

I believe I signed off on an IMAX print at their headquarters, but I didn’t get to see it with an audience until this week. Not all IMAX rooms are the same — some, especially in the malls here, can be relatively small and some can be like the Chinese Theater, which is unlike any IMAX theater on Earth in terms of its scale. I would say, for my tastes, [it’s] the best one I’ve ever been in, because you can get a really great view of the screen not right up on top of it, or if you choose you can get right into it but not have to strain your neck so much.

BTL: Working with your sound editors and mixer, at what point were you able to get into an IMAX theater to experience how it looked and sounded at that scale?

Morgen: We were mixing in IMAX on the Ford Stage at Fox, but we would go back and forth. We would take our mix over to the [Imax] Playa [Vista] headquarters — we probably did that four or five times, because we found that the room at Playa spaced the music out a lot more. We got to a point where we were going to Playa to take notes and then come back to the stage at Fox and employ them, almost blindly at that point, because playing it at proper scale on the Ford Stage, the stage is much smaller than the IMAX room, so we would just get blasted out.

BTL: You edited this yourself, which made it easier to continue working when the pandemic hit, but how did you bring your sound editors into the process — or was that dealt with later after you had your edit?

Morgen: I locked picture before I brought it into the sound design team, so I locked picture in March 2021, somewhere around there, and then I started my spotting sessions with the sound designers, which lasted for a couple of months. I would go back to my edit room to move things around, to accommodate sound hits, if necessary. I was certainly coming back to my edit room during the color correct to adjust pictures. Some of my edit points weren’t as obvious on my 11″ laptop [as in] the big color room. All the color was supervised within 650 hours.

I even went back and recut “Space Oddity.” After seeing it in the color correct, I realized that I over-cut it. There was a joke with my team about, ‘Are you ever going to be finished?’ and I would say, ‘No. When it’s on HBO — when it’s finally on television — I guess it’s finished then, because there’s nothing to adjust.’ I was lucky in that, while we ran out of financing probably in Year 3, we didn’t have a delivery date on the contract, so I was able to work as much as I wanted to work on the film until I felt that it was finished.

BTL: I was also curious about mixing differing songs together as mash-ups. Were you doing that on your own or with your sound team?

Morgen: No, all the mash-ups I did on my own. I was just playing around with sounds and trying to create refrains. Sometimes they were employed, because of the way I knew that they would resonate. The audience would bring their own expectation of them, so at the beginning, I started playing some strands from “Life on Mars?” and “Space Oddity.” That has a certain design and purpose of tantalizing and teasing and almost trolling the audience for the fact that I’m going to open up with “Space Boy.”

During the Berlin years, I introduced “Word on a Wing” as he arrives at a crescendo, which I then bring back when he meets Iman. The idea was to connect both of those moments — what the connection is, is up to you. I’m putting it out there for you to draw a thread, a connection. A lot of times, it was intuitive. It was no different than adding a shot. Adding a vocal to “The Mysteries” from “Absolute Beginners” just felt appropriate in the moment. I think that’s how a lot of the film was designed — it was very intuitive, allowing things to happen sometimes with [the] intent of purpose and sometimes with just intent of feeling.

BTL: I’ve probably been into Bowie since maybe 1979 or ’80, and I’ve read a lot about him, although your movie made me feel like I just scratched the surface. Were there many things about Bowie that you discovered yourself as you went along that you didn’t know about at all?

Morgen: I probably had your orientation going into it — maybe one rung up the ladder in terms of fandom than where you were coming at it [from]. I did have most of the albums, but I never read a book [about Bowie]. I’d never studied the interviews or anything, so I would say that nearly everything was illuminating and revealing, and revelatory. The years I spent going through his media from an artistic or a creative standpoint, were probably far more helpful than most of my academic education. Things he was teaching me about art and how to create and how to live life were just incredibly profound and resonated in a really deep way.

BTL: Earlier, you mentioned the narrative you created for the film. How different was that from the pitch you gave when you first met with Bowie? Was it at all similar?

Morgen: [holding up both hands in “zero” signs] The thing I presented him wasn’t a traditional doc — it was a hybrid nonfiction film, but it was something that was gonna require him to perform as an actor.

BTL: What was the longest assembly you had of the film? Did you end up having to cut it down from a much longer film to what it is now?

Morgen: Not at all. There was maybe one extra song at the end that I cut out before I locked picture. This wasn’t a whittling-down — by the time I got to the finish line, I was exhausted, if that makes sense. My assembly of it was probably a week before picture lock, put it that way. Each step was a little difficult to arrive at.

BTL: You’ve shown it to a bunch of audiences now, so what have the reactions been to it? I’m sure there could be 100 completely different movies about Bowie, so was there anyone who felt you left something out that they were hoping for or that they personally loved? Like, for me, it was the fact there was absolutely no mention or reference to Tin Machine, which was the last time I saw Bowie live.

Morgen: If I were doing a biography on David, Tin Machine would absolutely have a huge role in serving as a palate cleanser, allowing him to get to where we needed to go to, but following the threads of this film, I was able to have him arrive at that place without indulging in Tin Machine.

I have to resist getting prickly on these subjects, because when you watch the film, what you just did — you just brought something to the film that you know. The film was designed for you to bring that to the movie. I didn’t need to say it — you brought it. For me to say it would be redundant for you because you already know the information. If you don’t know about Tin Machine — if you’re someone who just is younger, just doesn’t know that they existed, it’s very unlikely that [when] you watch this film, you will feel like there was something missing between the mall and when he meets Iman.

That’s the measuring stick, and I think it’s a critic’s responsibility — particularly when dealing with biographies — to understand that. There have been two or three reviews that critique the film for what’s NOT in it, which is totally antithetical to what the film is about. To be honest, it would be very antithetical to Bowie, the idea of a list of known facts that the writer seems to have already known but somehow wants me to [depict] rather than allow the music to just play out in immersive IMAX. [They’d] rather have someone talk about David’s collaboration with the group. I think there’s a great place for that — it’s a book. There is another great place for it, which is a talking head documentary that someone else can make.

My concern going into this, from the beginning, was ‘how do I prepare the audience for the fact that they’re not going to get that information?’ I will say that the last four months, from the time we announced the film, everything has been geared towards trying to prepare the audience for this different type of movie. This weekend, as it opened up all over the world — that, to me, was the single greatest reveal. From South America to Australia, to Europe to Singapore, very few people were questioning the format. They seemed to just naturally pick up that this is the format for David.

What’s interesting is, I’ve seen comments from hardcore fans who say, ‘Well, this is only for hardcore fans. If you don’t like David Bowie, you won’t have an access point.’ I’ve seen the response from people, and that’s not true. It actually works really well if you have limited knowledge, because you’re not sitting there worrying about what’s not in the film. It’s the person who has the encyclopedic knowledge who is like, ‘Wait a second, they didn’t put in… they skipped over this or they skipped over that.’ You have to accept that you’re going to bring that to the movie and project [that onto it], and I designed it as such.

But you’re not supposed to be sitting there going, ‘They need to say it because I think the next person would need that to get an experience.’ The next person is all good. They’re having a great time. They’re learning about themselves, they’re learning about Bowie, and more importantly, they’re having a really unexpected cinematic experience. I felt there was a little bit of resistance, perhaps, when I started talking about the film back in April as a “cinematic experience.” Well, what is that? Aren’t they all cinematic experiences? That seems like a catchphrase, but I’m very happy to see that people are now describing it as such because there is no other way to describe it. In a way, that’s really been surprising. At the end of the day, it’s a bit of an experimental film, and some of my favorite avant-garde work also has a pop sensibility, so it can hopefully work on multiple levels.

Moonage Daydream is still playing in theaters nationwide — but not in IMAX. You may have missed that opportunity unless demand forces NEON to bring it back to IMAX screens.