E.T. was first developed as a horror film entitled Night Skies. In fact, production was far enough along on this version that Spielberg enlisted creature effects master Rick Baker to build an animatronic alien with the aid of mechanical developer Doug Beswick and moldmaker Gunnar Ferdinandsen. Reportedly, Spielberg felt the project was headed in too dark a direction, and all ongoing plans were aborted. It was rumored that Night Skies might one day be put back into production, but perhaps Spielberg finally reached that goal by producing Super 8 with director J.J. Abrams instead. Regardless, with Night Skies terminated in the early 1980s, Spielberg made Raiders before embarking on E.T. and nearly simultaneously producing the horror-thriller Poltergeist.

When E.T. got back on track with a new script by Melissa Mathison, one of the most important craftspeople aboard the more inspirational production was cinematographer Allen Daviau, who had shot Spielberg’s experimental short Amblin’ in 1968, a title which would become the namesake of Spielberg’s production company in the 1980s and onward. Daviau, who had not worked with Spielberg since Amblin’, shot the movie enveloped in a beautiful glow on its sets and in its carefully chosen locations. While interiors were shot at Laird International Studios in Culver City, many exteriors stretched across Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley, including the towns of Tujunga, Northridge and Granada Hills. Additional exteriors were in Marin County, California, north of San Francisco, and the northwestern-most area of California in Crescent City, for the many forest scenes. Throughout these locations, Daviau provided an on-screen atmosphere which suggested horror in the opening scenes of the government stalking the abandoned creature, to warmer tones of star Elliot’s home life with his adopted friend, E.T. himself.

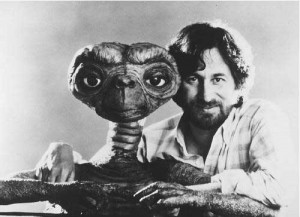

Enter makeup and creature expert Craig Reardon, a disciple of makeup legend Dick Smith’s (as Baker had been) who assisted Smith on Altered States (1980) and created the myriad makeup and puppet effects for Poltergeist. Spielberg brought Reardon into his office, drew the blinds and barred the door, and showed Reardon the first creature, soliciting his crucial opinion. When Reardon replied that he was not overwhelmed with the design, Spielberg enlisted the 20-something Reardon’s help in re-designing the character’s appearance, including the important paint job. When Reardon asked what color Spielberg wanted the creature to approximate, Spielberg noted that it should look like human skin but as seen in a swimming pool. Working diligently, Reardon presented Spielberg with the look of the final renowned creature that millions came to love on movie screens in the summer of 1982.

One problem that had not been tackled yet was the creature’s “heart light,” a job which was assigned to makeup veteran Robert Short (who had worked at Don Post Studios creating memorable masks). Starting from scratch, Short designed a heart light that worked inside versions of E.T. used for wider shots. An E.T. suit was also created for scenes where the creature walks in full shots, notably in the kitchen sequence.

One of E.T.’s final effects touches, only hinted at during the beginning of the film, was the spacecraft that drops off and later picks up the creature. Star Wars illustrator Ralph McQuarrie had so beautifully rendered that film’s many otherworldly elements, Spielberg enlisted him to design E.T.’s ship, which was built in part full-scale on stage at Laird but created for its climactic full-scale take-off shots as a model, photographed and composited into the film by Muren’s team. This final sequence was a coda in ways to the ending of Close Encounters and provided E.T. with its final piece of cinema majesty.

E.T. broke all box office records when it was released in summer of 1982, playing throughout the rest of the year and into 1983 at some locations. Other films later broke its records, but even 30 years after its phenomenon, E.T. remains a cultural icon. Of note, the film was re-released in 2002 as a “special edition” with new footage, mostly consisting of computer-generated modifications.