32 Sounds is unlike any other documentary I’ve ever seen, mainly because it started out as a live art performance project by filmmaker Sam Green — working alongside musician/composer JD Samson — that was supposed to have its big-screen debut at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival before being relegated to a virtual premiere when the festival was forced to pivot due to Omicron.

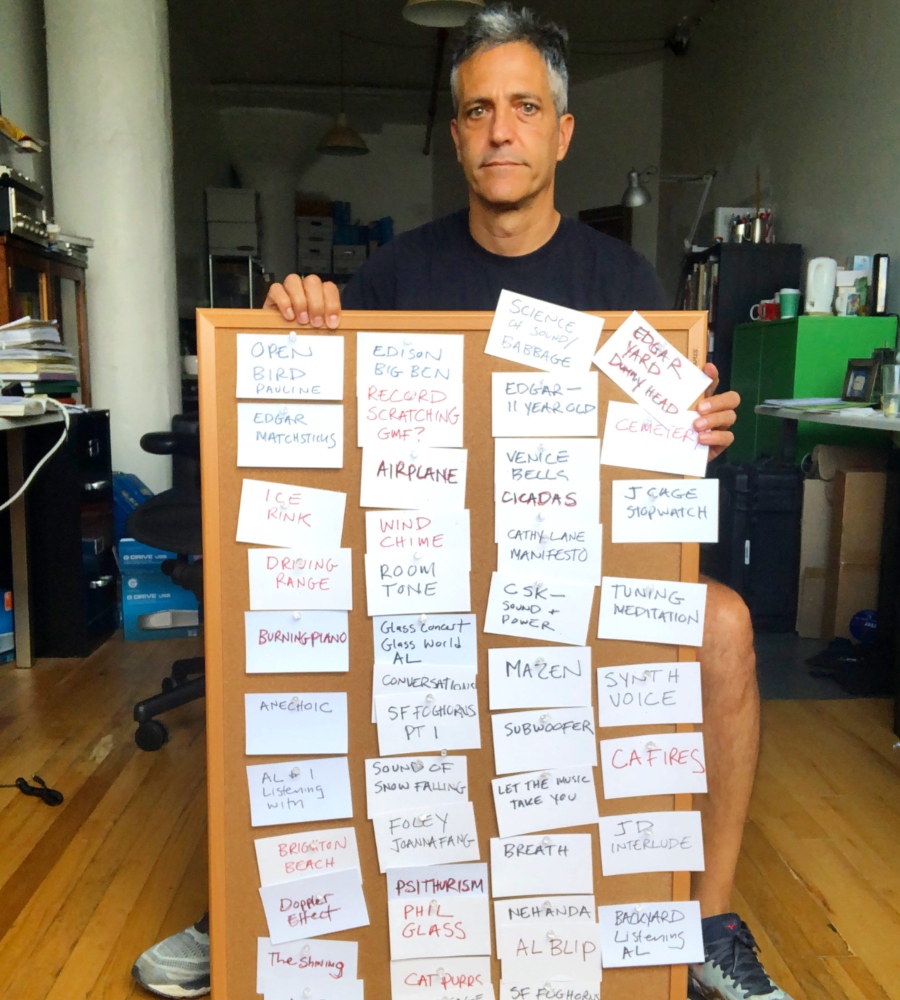

The movie takes a look at sound through a number of very different avenues, from experimental Composer Annea Lockwood and her field recordings of rivers to the work of Foley Artist Joanna Fang, to that of deaf sound artist, Christine Sun Kim, and binaural sound expert Edgar Choueiri — all tied together with an interactive aspect that has made 32 Sounds such a success as a live performance.

Last year, Green held a string of sold-out live performances of 32 Sounds at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM), and Abramorama is now handling the movie’s theatrical release with a number of versions, including a “theatrical headphone version” that includes a live sound mixer making sure that the movie sounds the way Green (and his two-time Oscar-winning Sound Designer Mark Mangini) intended it. It will also be released theatrically and streamed in more traditional formats that allow for enhanced headphone listening, in addition to being fully accessible for those with both sight and hearing impairments.

32 Sounds recently launched its national release with screenings at New York’s Film Forum, which will debut the “theatrical headphone” iteration of the film at one screening per day, and Below the Line jumped on Zoom to speak with Green about the reasons why he has invested so much time in making sure the movie is seen and heard in the right way.

Below the Line: I had a chance to see the live performance of 32 Sounds at BAM last year, and then I saw it at Film Forum in the theatrical headphone version, giving me a good comparison between two different versions of the film. I should mention that I’m a former sound engineer myself.

Sam Green: It’s funny because there are so many people who know so much more about sound than me, so I always have to be very humble, because as a sound engineer, even a former one, you know a lot about sound.

BTL: You’ve been making docs for many years, so what made you realize you wanted to do a movie specifically about sound?

Green: I had made a documentary about the Kronos Quartet, that was my previous film. In making that film, I thought a lot about sound and listening. I realized [that] with movies, most times people listen in super passive ways. You just kind of sit back. With the Kronos Quartet, if you just sit back, their music is okay, but if you really engage your ears, it’s remarkable and dazzling, and transcendent.

Figuring out how to make people listen in the context of cinema was something I really struggled with. I learned a lot about contemporary classical music, and once the pandemic happened, all the screenings I had with the Kronos Quartet were canceled in early 2020. I just had a lot of time, and I was reading a lot of books about sound, just out of curiosity.

I said this in 32 Sounds: I read a book about Pauline Oliveros, and there was a line that said her longtime friend, Annea Lockwood, has recorded the sound of rivers for 50 years. I’d never heard of Annea Lockwood, but just that image, I was like, ‘I love the sound of rivers. Who is this person who’s recorded rivers for 50 years? I’m intrigued.’ I just started Googling her, and a lot of her music is online. She’d made several records that are just sound maps of different rivers, where she goes from the top to the bottom — the Hudson River, the Danube River — and makes these portraits and they’re stunning, but she’s got such a wide range.

I just wrote to her [and] said, ‘Hi, I’m curious and interested in sound. Would you be up for talking on Skype?’ She wrote me back and said, ‘How about this afternoon?’ Nobody was doing anything, so we just struck up an ongoing conversation over Skype and email. The more I talked to her, the more I was really taken with her, taken with her ideas about sound, and just inspired. It got me fascinated by sound and really loving sound and interested [in it].

Sound is endlessly fascinating. You might feel the same way or maybe you think it’s more like work, but there are so many different kinds of people who are smart about sound. There are musicians, composers… there are movie sound design people, [and] sound studies as an academic discipline where there are smart people. Field recording people are very smart about sound and miking sound. It’s a neat world.

BTL: I’ve only seen one other documentary about sound, Making Waves, but that was primarily about movies and the different elements of it. When you decided to make this movie, you must have gotten sound people involved early on, both for the recording and mixing and for creating the live element you’d be doing.

Green: I got lucky as heck because early on, I connected with this guy, Mark Mangini, who is a sound designer who just won an Oscar for Dune, Mad Max, [and] some of the early Star Treks. At first, I just started talking to him, asking questions about sound. A big part of my research process is just asking people questions who know a lot about the subject. He’s incredibly smart and thoughtful about sound. I think, for him, it was interesting because very few people pick his brain about sound. He’s got a lot to say, but people would probably just be like, “Can you make an explosion sound good here?” At a certain point, I said, ‘Will you work with me on this?’ and he was thrilled to do it. He was my sound guru, in a way.

BTL: I know this premiered at Sundance 2022 which ended up going virtual, so you were robbed of the live performance you planned there, but I don’t think I realized that literally the entire movie was done during COVID.

Green: [It’s] not easy to make a film during COVID. I made a short film about Annea Lockwood during that time and filmed her rehearsing with some musicians, and they were all wearing masks. In a way, I’m so opposed to showing COVID, because now, if you see something with people wearing masks, you’re just like, “Oh, God.” It ages really badly, so with Annea Lockwood, we wore masks and she didn’t. I just tried as hard as I could to not show COVID.

BTL: That makes sense. How did you end up connecting with JD Samson, who is a huge contributor, and not just to the music in the film but also to the live performances?

Green: I had done a piece for the Whitney Biennial in 2019, and it was a live cinema portrait about a guy named Jim Farrar. He’s an old, very New York character, and [to] the person who sort of commissioned that at the Whitney, I said, ‘I’d love to have live music,’ and that person said, ‘How about JD Samson?’ And I said, ‘Wow, I’m a fan, but I don’t know JD.’ That person put us together and we had a great time.

And so, then I said to JD, ‘Would you work on this longer piece about sound?’ And she said, ‘Yeah.’ I’m lucky because she’s not only a great musician — the music she makes really speaks to me and resonates along the emotional themes that interest me — but she’s [also] a great muse, and JD is a great performer, so I like filming JD and I feel lucky to be on the stage with her.

BTL: You had obviously transitioned to virtual at Sundance when you weren’t able to perform it live. Had you always planned this four-way release, so people could watch the movie in all these different formats?

Green: I’d made several other live cinema pieces. I mentioned the Kronos Quartet one and with that, they play and it’s about them. The power of that piece is you’re learning all about the Kronos Quartet, their 50-year career, and they’re sitting right there. [For] that piece, many people said, ‘Why don’t you make a non-live version of this?’ but it just didn’t make sense, because so much of it is hearing their music in person.

This is the first one I’ve made that lends itself to that, and the Sundance thing was a total tragedy because we were going to do a big show at the Egyptian [as] opening night film. We had two weeks to figure out how to make it virtual, which ended up working out, and that made me feel like, “Oh, if that worked, maybe this could work as a regular movie.” At some point, after the BAM shows, somebody from Film Forum got in touch. Mike Maggiore said, ‘Could we take a look?’ and I sent it to him, and they said, ‘We’ll show this.’

That made me feel like I could show it at Film Forum, and then I got in touch with Richard Abramowitz (the “Deconstructing the Beatles” series), who’s an old friend, and he said, ‘We could book this.’ In some ways, the movie has found its own path. In the world today, as a filmmaker, it’s so hard, and you have to be so nimble that I like the idea of having multiple iterations of a movie that can play in different ways and forms.

BTL: When you had to do the virtual version at Sundance, did you already have some kind of mixed version to make it easy to do that?

Green: When I make the live pieces, I mock them up as a non-live thing. I’ll record my voiceover and put the music in, so it’s like the film mocked up with all the elements, so we can just use that.

BTL: Having seen the “theatrical headphone” version, I felt there was only one part that didn’t work as well as the live performance at BAM — the “I Feel Love” section, because it’s not quite the same with the subwoofer blasting and people dancing around it.

Green: It’s one of the things that pains me a little because, in a theater with people, you can kind of control them, in a way. You can make them have the experience you want them to have. When somebody is watching it at home, you’ve got no control. [chuckles] It’s like you have to let go, but still, I would like everybody to be getting up and dancing in their living room.

BTL: When I saw David Byrne doing American Utopia on Broadway, it was such a staid Broadway audience, and at one point, he said, “You know, you can stand up and dance if you want,” and literally, everyone did just that. You can literally make anyone do whatever you want when you’re there live.

Green: With the live show — I’ve probably done 40 or 50 of them by now — [and] when we first made it, I had no idea if people would get up. I sort of had this fear that we’d do this section, and I’d say “You can get up if you want” and nobody would, and it’d be extremely awkward. Every single show, people have got up. The thing that really strikes me [is that it] completely resets the energy. It’s like the seventh-inning stretch.

Before that, people are starting to settle into that way in which you see a long movie and you get kind of catatonic. After it, you can feel there’s a renewed energy in the room, which helps, then the piece sort of slowly comes in for a landing, and it ends with energy. As a kind of energetic intervention, I’m delighted by the way it works in the live version. You are one of the few people who has seen both.

BTL: Going back to “I Feel Love,” you have three very prominent songs in the movie of which you use a lot of them. Was it different licensing them for doing the live show versus the theatrical release? Does it get very complicated?

Green: You have to license it a lot more when you do a theatrical film. I fell in love with “I Feel Love.” It’s such a magic song and probably a little bit to my chagrin, we pursued that til we got them to license it to us. But licensing music is painful [and] it’s expensive.

BTL: But also, Phil Collins’ song “In the Air Tonight” is a specific part of the narrative, and I can’t imagine having to replace that. “Ain’t No Stopping Us Now,” too.

Green: It’s fair use. It’s commentary. Fair use is pretty clear in that kind of situation.

BTL: That’s good to know. As I was watching the version with the headphones, I was thinking that it must be like this band that plays a song live over and over for many shows and then has to go into the studio and record the perfect version, and they then have to play that way live for decades. It’s something I’ve experienced, so it must be difficult to commit stuff to tape, as it were.

Green: It’s a little bit like when I watched the theatrical version, I’m like, “Oh, I said that word ‘performance.’ I wish I could say that one word better.” There are all these tiny things, but in general, I had seen it with an audience through speakers for the first time last week. There was a screening at Upstate Films in Rhinebeck. I had not been 100 percent sure how it would work with an audience in speakers. Every theater is different, it’s crazy, but [it] really worked. I was relieved and really delighted. You’re trying to achieve a certain effect, and there are different ways to get there. There are a lot of variables. Somehow, there were a lot of different variables, but it hit in the same way, so that was a big relief.

BTL: I do enjoy the use of headphones in both versions I saw. We’ve gotten so used to wearing certain glasses for 3D, but it’s always about the visuals, although Dolby and IMAX are just as much about the sound. What are the plans for the theatrical headphone version? Is it going to be like a roadshow where the headphones are sent to different theaters?

Green: With Film Forum, we’re doing one show a day with headphones. It’s not live narration or live music, but we have somebody mixing in the back, because — and you would understand this as a sound engineer — if you just do the headphones, you’re missing a lot, because the headphones, the dynamic range is narrow in the headphones — you don’t get the high highs or the low lows. We have somebody mixing in the back who, in certain sections, will bring up the subs.

So “In the Air Tonight,” you’re hearing it in the headphones, but it’s also coming through the house and you feel it. People often say, ‘Why do you need the house if you have the headphones?’ The answer is, because you feel it. A lot of theaters, it’s just the speakers. Some theaters will have headphones, and our person mixing it, and some theaters will just send the headphones and they’ll play it through the headphones. There are a lot of different iterations, which, like I said, I’m happy about.

BTL: Part of me wants to go to Film Forum and just watch the live sound mixer to see what they’re doing. I wasn’t sure if, at my screening, she was just turning on the speakers or boosting them in places.

Green: You probably know this, too, but movies are getting mixed louder and louder. Theaters are starting to turn down. Either you have to mix your movie loud, or you have to risk mixing it at the normal levels, and the theater will play it quiet. It’s this sort of conundrum. I’m gonna get Mark Mangini to write a letter that I’ll send to every theater saying like, “Could you please play it [at]…?” He does it in a very official way, because I don’t want them to play it quiet. That would be the worst. Anyway, this is the kind of stuff I’d never thought about before making a movie about sound, where it all really matters.

BTL: Mark must really understand that, since I’ve spoken with other sound mixers and editors, and most people don’t understand that when they’re mixing a movie, they need to take into consideration every sort of speaker and environment, including people watching on their phones. Before I let you go, I was pretty intrigued with the trailer Abramorama cut for 32 Sounds, because it’s a movie that’s probably tough to sell in just two minutes.

Green: A movie with a main character, a movie with a clear plot, there are so many easy kinds of movies to make a trailer for. This was so hard. I’m not a good trailer editor, but Richard works with this guy named Jeremy Workman, who is the son of Chuck Workman. He’s an L.A. documentary filmmaker, old-school, who does all the videos for the Oscars, and he’s like an illustrious elder statesman of [the] documentary [world]. Jeremy is his son and made this great trailer that gets the spirit of the movie. With a trailer, you want somebody to want to go see the movie, to be intrigued enough and not confused. I feel like it does that, and it’s not easy to do for this kind of movie.

BTL: Definitely. Even when we see the tree falling the first time in the movie, you’re like, ‘What is that?’ because it’s out of context, but I definitely liked the movie a lot. Maybe I’m an easy lay due to my experiences as a sound guy.

Green: [laughs] You have to put that in your review: “I’m an easy lay for this movie.”

32 Sounds is now playing at the Film Forum in New York City with a single “headphone version” each day. It will also be playing in other theaters around the country as a straight doc, and you can find out where it will be playing here.