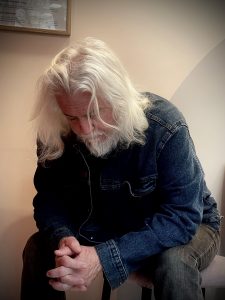

Robert Richardson‘s career is a marvel. The cinematographer, whose first feature film was Oliver Stone‘s Salvador, has shot a long list of influential films for both audiences and storytellers. He’s collaborated numerous times with Stone, Martin Scorsese, and Quentin Tarantino, and he’s won three Academy Awards for his work on JFK, The Aviator, and Hugo. Not only are they great works of imagination and ingenuity, but Richardson and his collaborators made them every bit as personal as they are lush.

With Richardson behind a camera, audiences often see the world as the characters see it. They feel how they feel. For two or three hours, with Richardson’s eye, you walk in their shoes. Especially when they have tacks in them.

The artist recently collaborated with Antoine Fuqua on The Equalizer 3. In what may be the final chapter in the series, the story sees Robert McCall (Denzel Washington) journey to Italy and battle his own demons in a country greatly defined by religion. As McCall is pulled between the light and the dark, Richardson shows the character’s internal struggle with piercing blackness and optimistic light.

Recently, Below the Line had the pleasure of speaking with Richardson. The interview started off on a less than ideal note due to technical issues over Zoom. The cinematographer was accommodating and patient, allowing us to pivot to another means of communication.

Before we got back on track and covered parts of his career and point-of-view, as well as his optimism for the state of filmmaking today, we talked about his days of discomfort as a cinematographer. Hence, some of the questions and subjects that follow.

Below the Line: Well, just to get back on track, you were talking about as a cinematographer, sometimes it’s difficult to be flexible on the day in terms of following what the performance is giving you. With Denzel Washington, what are moments where you do have to pivot on the day, where it’s uncomfortable?

Richardson: Well, it’s not so much uncomfortable as it is what you initially said, flexible. I’ve worked long enough in the field to understand that actors generally want to perform and go where they want to go. There are certain directors who are extremely specific with an actor and say, “You’re going to be sitting here. You’re going to be doing this,” and there’s other directors that prefer to work with letting the actor move in any way that they prefer. It’s all a question of the style and the attitude towards collecting the best performance from whoever you’re working with.

With Denzel, you’re not always certain where he’s going to be moving, and you’re not certain you have lights or lighting equipment that can get you into the proper feel if you’re doing interior work, which did happen a number of times, and the way he walked around the room upstairs, or sequences like the attack on Vincent’s brother.

Those kinds of situations, you just have to move with and learn how to contend with the limitations of what you’re shooting physically. These were all real locations, so a lot of them were practical locations. Some were studio in Rome, but overall, I would say the vast majority were not. They were practical. So if he decided to move one place or another, and make the kill one place or another for that particular scene that we’re talking about with the bottle and then the knife at the edge of the car, that required me to be capable of adjusting the lighting for that scene, because it did require a certain amount of… Well, in order to do stunts like that, he had to get locked down to certain positions, or roughly within a certain number of positions, but they were both pretty, they were both… How do I say it? Their energy levels were high.

Not so much Denzel, but the actor that was working with Denzel was not quite as tempered as Denzel was, so you had a different motion with him. And that was pretty much the same thing that happened inside the square [sequence] with Vincent, when he shoots the ear off of the policeman and McCall comes out and says, “Don’t kill him. I’m the one who shot your brother.”

Again, motion in there, it was up to them to determine where they went. I did not know exactly where they were going to be going, particularly Denzel. He made his choices, and sometimes it turned out to be a 15 or 20 foot move that was different from what I was anticipating, and I had to be prepared for that.

BTL: That sounds very drastic, especially for action, a 15, 20 minute foot difference.

Richardson: I think you’re right, but this is something that we deal with all the time when you’re shooting. For me, it’s the process. You have to work with actors, and it’s to the benefit of the film. If he is most comfortable in this, that or that, I’m going with that. I mean, his work is more important than my work. If I can’t quite get my work to where I want it to be, the most important aspect is of course with the film, what’s up on the screen when people go to see it.

BTL: The opening shot, just that huge exterior of the winery and everything, it looked great. Was that drone photography?

Richardson: It was a drone that was enhanced, because we were intending to shoot that originally in Sicily. We were looking for a different time period and it was shot in a time period that wasn’t conducive to creating the actual… We wanted it more at harvest time and we ended up getting it more in the fall after harvest. I wasn’t on that particular shot. That was a second unit piece, that aerial, and then with visual effects added to it to make it what you basically see to some extent, by putting in the farm in which we actually did shoot the background and the truck.

BTL: What are your feelings on the state of drone photography?

Richardson: I’ve done a fair amount of drone work. I think the issue with drones… It’s a tool. Let’s be realistic. It’s a tool that’s great to utilize. It reminds me a little bit of the time period in which zooms first came into a prominent use and they were being overused in terms of making zoom moves, et cetera, or anything that’s brand new, people sometimes have a tendency to overuse.

I think that we’re finding this attitude of putting a drone up in the air and shooting an overhead and, “Oh, you got it. Okay, let’s move on,” and not being as creative as you could possibly be with it. The drone has its limitations just as any tool does, because it kicks up air, but at the same time, it’s vastly superior in some ways to a helicopter in many situations, because you can get a lot lower and do your aerial work in a way that could be a long tracking shot, and they’re becoming much more stable.

So, they’re going to improve more and more as cameras get lighter. You don’t require heavy drone work and you can work with lighter drones with a better quality and more flexibility with your lensing. I myself would love to be able to operate my own drone as a pilot, but it’s not possible for me because you need to be a pilot clearly to fly those.

For example, with a car, I like to operate when I’m in a car. I like to operate the head of the car, the remote head, but the joysticks, I use joysticks, have to be very well tuned. I can’t quite get that with drones and I don’t quite understand how they utilize them, because they’re almost like toys in some of the cases of the drones I’ve worked with. They’re so small, but these guys are extraordinarily talented. But they’re being used in ways which provide something brand new, but at the same time, are also becoming overused and not necessarily reflecting anything beyond just having fun in some cases.

BTL: Correct me if I’m wrong, but was it on Casino that you became comfortable as an operator?

Richardson: I felt comfortable operating the camera from the very beginning.

BTL: Okay, I misread.

Richardson: Yeah, I think that what that statement comes from is the fact that on that film, operating and lighting were the two things that I was doing, because Marty doesn’t take any input into what the camera does. In other words, if I had an idea for a shot, initially he was not willing to listen to anything I had to say other than if it had to be rectified from what he had written down in his notes. If I couldn’t achieve it due to the location, then we could shift it. But otherwise, that would be the only input I would have in terms of the camera work, particularly on Casino, which is my first film with him.

BTL: Has the process with him more or less remained the same throughout the years?

Richardson: Yes. I think that there was some flexibility when he writes docu style on that film. There was also a little bit more flexibility when we got to Bringing Out the Dead, but minimal. It’s very much like Quentin, there’s just no flexibility. You’re doing a shot they need and they want, and that’s what you go after. I mean, those two are very similar in terms of, “I want this, and this is the shot, and now you give me that shot.” And that’s what I do. I try to give them the shot that they put down on paper.

BTL: Have you noticed over the years Bringing Out the Dead becoming more of a favorite among Scorsese fans? Is that gratifying?

Richardson: Absolutely, because I think the problem that Bringing Out the Dead had when it first came out was it was falling on the heels of another film entirely, and you need to go back to the films that… For example, Goodfellas influenced greatly the reception that Casino had. Casino is a masterpiece, and it was just because it appeared… I mean, Taxi Driver and Bringing Out the Dead, you’re dealing with similar issues there. I’m quite happy that it’s seeing a resurgence, with both those films actually.

BTL: It sounds like your process with Oliver Stone was very different from Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese, am I wrong?

Richardson: Yeah, no, you’re absolutely right. My relationship with Oliver began, we were both relatively fresh too. I was far more fresh than him. I mean, I wasn’t even in college yet. For me, he had so much more experience in the real world in having done his own work. But yeah, we were both finding solid ground and we grew through the process with each other of trusting and not trusting. There was more of an impact, that I could have more of an impact with him than I could have with either Marty or with Quentin in terms of shots. But in the end run, it’s always the director.

It’s the same thing with Antoine, the same thing. He has these ideas and you’re going to make those ideas happen, and when we go into certain sequences and sometimes he’ll say, “Bob, I would prefer to have less light, more light. I don’t see this, I don’t want…” And that is what you do. You create those looks for them, and that’s a great joy.

It doesn’t fall away from me. It becomes something I love. I love doing it, and trying to make a director happy, and also trying to make, in some cases, in films such as Equalizer, it’s also making a studio happy. Which is quite vital, and many of us forget about that, that you’re not just working for one person, you’re working for many people that are putting up money.

A film like Equalizer is very much influenced by number one and number two that came before, Equalizer 1 & 2, as well as the studio and what they’re expecting because it’s a trilogy and they want the third to have a feeling that in some ways it’s still a sibling.

BTL: Were you thinking about [the late cinematographer] Oliver Wood’s work on these films? Did you take anything away from them that you wanted to create a consistency with Equalizer 3, or did you also view it as a standalone film?

Richardson: We discussed this. It was a pretty interesting discussion. We initially just wanted to call it Three, and it didn’t happen that way for obvious reasons, but the way we looked at it was, “Okay, this is Three. It’s not EQ 3, it’s Three.”

Of course, you’re making Equalizer 3, but our feeling was it’s a film on its own, but it had the same same character who’s moving through the time periods in which McCall has evolved. We were hoping that it would feel… Maybe particularly because it was also filmed in Europe and it took on a touch more of a European flavor for us, more of an independent, even though it was a very large studio production, if that makes sense.

BTL: It does. It plays like a spaghetti western.

Richardson: I read a review that ended with, it was not a highly positive one, and it was, “This is a film that’s The Good, the Bad and the Very Ugly.” Well, you know, I’m going to go with that one. I’m going to put that in my positive category. You may mean it in a negative one, but I’m going with it. If you want to align this and just make it part two of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, I’m okay. Put the “very” in front.

BTL: You read reviews, huh?

Richardson: Well, I do. I got up this morning because it’s opening in Europe early. I think it’s opening today in Europe, and I’ve been curious how reviews turn out. I have my thought patterns on what might happen or not happen. I enjoy reading some reviews. I do feel a certain level of pain on some level for bad reviews. Some people are highly vindictive in their writing.

BTL: They can be. I always think be critical but don’t write something you wouldn’t say to someone’s face.

Richardson: I think that to a certain extent, you’re probably right. Sometimes, things are just said that are so far off the mark or they’re literally a duplication of something else that somebody else wrote, and I don’t know who wrote it first.

You read one review and you’re suddenly going, “Well, wait, how did we end up with almost exactly the same remarks on these two reviews?” And that’s where I get a little more flustered, because it’s extremely difficult to find the same syntax in review after review.

BTL: Do you also feel joy when your work is as well received as it’s been?

Richardson: It depends. I can’t remember being well received.

BTL: Really? Your work?

Richardson: Recently? No. I’m happy when anyone’s actually reviewed well, directing, production design, editing. As you know, reviews don’t necessarily contend with below the line. Other than a cursory remark. Serious involvement is rare. For someone to do a review, below the line’s work in a manner which examines the quality or lack of quality in a serious and more sustained manner than one or two lines…

BTL: I want to end with talking about the unknown, because you’ve experienced that so much as a cinematographer, whether it’s the wild nature of Natural Born Killers or the overbearing colors in The Aviator. Have you sought the unknown in your career?

Richardson: You’re absolutely right, I do chase what I don’t know. I don’t necessarily chase it in terms of choosing material that I’m willing to shoot or not shoot, but when I’m given the opportunity to evaluate, for example, LED screens, that’s all new to me. Working heavily in the visual effects world is something that I’m intrigued by. For example, I love the work in Avatar and I would love to have been more involved with that and that type of work.

The unknown to me is a place I want to go, but it’s not something I hunt for or utilize as a decision maker. I make my choices based upon who’s… Like with Antoine, I have a close relationship with Antoine, and I would make anything that Antoine wants to make.

The same goes for Quentin and Oliver, as well as Marty. I would make anything with these people, because we come close to family. Filmmaking is a family, and my bond with these particular gentlemen is relatively high.

BTL: Like family, it can be complicated, too, right?

Richardson: Very much so, and it’s true with the crew you work with. My crew I’ve worked with for decades in some cases, and it can be difficult for them and difficult for me, but there’s a brotherhood that’s built. I was watching a doc about the [Florida] Gators, and they mentioned the fact that brotherhood is one of the most vital elements of why a season can be successful or not successful, is forming a relationship with each other and a level of respect and working with the strengths and weaknesses and finding a bond. And that’s true with filmmaking, and that’s why crews are so vital all the way through. My graders, and they’re not just my graders, they work with many different people, but that is a fascinating aspect which doesn’t get talked about a lot. Grading’s enormously vital to current cinematography.

Many cinematographers have not shot film or wouldn’t know how to expose it properly. To a certain level they could do it, but they’ve had the capability of utilizing very fine-quality monitoring to work their lighting out. And so, when I was able to work with the first ALEXAs, I was extraordinarily happy to do that, to try 3D with on Hugo.

People ask me today, “Do you care whether it’s film or digital? Do you prefer one?” I don’t prefer one over the other. I love film because I’ve shot film for many, many years, but I also have a love of digital and the way it’s progressing continually. It’s on a constant evolvement and evolution. It would be great to see where it ends up. It’s certainly not going to end up where it is right now.

BTL: As you said with drone photography, it’s not good or bad, it’s just how it’s used. Always about intent and execution, right?

Richardson: Exactly. It’s the same thing that happened with lighting. Once the film stocks got to be higher, suddenly, oh, you don’t need lighting anymore. And then when it went digital and suddenly you’re at 800 now and you’re moving to 2000, why do you need lights? Wait a minute. There is that thought pattern that you can do more without it, but you still need to create a look. If you’re just recording what’s in front of you, then you’re creating a documentary that has actors.

What I’m trying to say is, you’re utilizing the documentary approach, which is very much what a lot of films that are currently coming out have. And to its benefit, that began very early on when newer film liberated itself out of 25 ASA, 50 ASA, 100 ASA, and started to move into lighter cameras, lighter lenses, faster lensing, et cetera. And that progressed all the way to the point in which you’re sitting right now with 1600, 2000 ASA, and you’re essentially using NDs to get back down, and you’re using negatives to mold rather than add light.

BTL: That’s something that I see in a lot of reviews these days. “Why is this movie so darkly lit?”

Richardson: Well, not just the look, it’s the camera moves. Too much, it’s gone too long on the shoulder. “Put it on the shoulder. Let’s shoot.” Well, wait a minute, wait a minute, wait a minute. “So, I’m basically just going to shoot and hold a wide shot. I’m going to do this, I’m going to do that.”

You don’t have the choreography of certain directors, the ones that are masters. So many others are utilizing just shooting, capturing the sequence the easiest way possible. Well, not necessarily always the easiest. Of course, everybody has a strong love, but you find that we’re falling prey to what seems the easiest, which is putting a camera on your shoulder and shooting.

BTL: And no sense of point of view.

Richardson: Yeah, or little point of view. Sometimes in some films, you go, “Oh my God, that is brilliant. Oh, what happened to the rest of the film, or what happened to the other scenes? Why are we only getting 20% of the quality we should be getting? The director’s outstanding.” And so, that’s kind of the place that we’re in right now for good or bad.

The other side of the coin is that a lot more films are capable of being shot. For example, your iPhone is a very good tool. We didn’t have that. So, many people are learning vastly different ways. The whole idea of what a viewfinder is, you’re not looking through a viewfinder anymore, you’re looking at basically your iPhone, and that’s what you’re framing off of, your large iPhone. I think you have a huge issue there. Cameras are dropping lower because not looking through eye pieces, so you’re looking down into whatever your little monitor on your camera is, not through the eyepiece.

And if you look at how lensing has gone down lower, it’s not on the shoulder, it’s down lower because the cameras are lighter and they’re often looking up, just because that’s the easiest way to do it with a viewfinder, which is essentially a small, or rather a larger version of the iPhone. Not necessarily an iPhone, but you know what I’m saying in that respect.

BTL: Would you say you’re hopeful overall about where cinema and filmmaking is going?

Richardson: Absolutely. I think we’re in a great place. Many, many people are shooting fantastic films because they’re being given the opportunity to do that in lighter and lighter weight, in less and less expensive manners.

The Equalizer 3 is now playing in theaters.