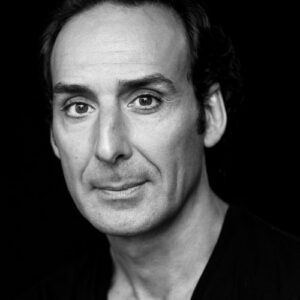

After receiving seven Oscar nominations, Composer Alexandre Desplat finally won an Oscar for Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel in 2015. That was followed a few years later with another Oscar for scoring Guillermo del Toro’s Oscar-winning The Shape of Water. In fact, Desplat has been nominated for 11 Oscars in total, including three for work he’s done with Anderson.

Anderson’s The French Dispatch is an odd anthology of stories centered around a fictional American magazine based in the French town of Ennui-sur-Blasé, the film telling four particular stories from the last issue after the death of the magazine’s editor, Arthur Howitzer, Jr. (Bill Murray). The writers of those stories include Owen Wilson’s Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson), the “Cycling Reporter”; Tilda Swinton’s critic J.K.L. Berensen; essayist Lucinda Krementz, as played by Frances McDormand; as well as Jeffrey Wright’s Roebuck Wright. Those four are just the tip of the iceberg for Anderson’s amazing ensemble that also includes Benicio del Toro, Timothée Chalamet, Elisabeth Moss, Jason Schwartzman, Liev Shreiber, Christoph Waltz, Edward Norton, Willem Dafoe, and many more.

More importantly, it reteams Desplat and Anderson for another terrific collaboration of quirky musical ideas to match Anderson’s distinctive cinematic storytelling. It’s such a fantastic and original score that it should get Desplat back into the Oscar race, and actually, Desplat’s score just received a Golden Globe nomination earlier this week.

Below the Line got on Zoom with Monsieur Desplat, literally the day after he returned to California after almost two years abroad, because the borders had been closed due to COVID.

Below the Line: I’m not sure if the last time we spoke whether I asked you how you got started in film composing. Did you go to school for composing and that led you to scoring films?

Alexandre Desplat: I was a flautist. I started music when I was five, but when I started going to the movies, when I was in my teenage years, I realized how music was important in these films. I started to become passionate about music and collecting theme scores, American theme scores, European theme scores, and I just dreamt of becoming a composer for the cinema. I never dreamt of being a composer for a concert, but cinema was my passion. I started with a short movie and another short and another project, and then a feature and then slowly but surely, I became a film composer.

BTL: Did you have a favorite film composer whose work you admired in particular?

Desplat: We had a great French School of Film Music — Antoine Duhamel, Maurice Jarre, Georges Delerue — but I also loved the Italians, Nino Rota, but all the Americans. Of course, there’s the classic history of [Max] Steiner, [Franz] Waxman, and [Erich] Korngold, and Newman. I think I learned almost chronologically, and then again, Jerry Goldsmith, Bernstein, of course, and they became my idols. I was raised by parents who had lived in America and studied in America and got married in America. So my childhood was really charged with this passion of California. I think subconsciously, there was something pulling me towards California and American culture, as simple as that.

BTL: You’ve worked with Wes on five or six films so far, so I assume when he does a movie called The French Dispatch, it’s not even a question that you’ll do the music on that one.

Desplat: I must say that through the years, there’s no question I’m not doing a film by Wes, because I know that the world that he’s going to offer to me will be different from the previous one, and it would be a new adventure and a new challenge. We’re good friends, and there’s no reason for me to even read the script.

BTL: But I assume you still do read it, so at what point does he actually give you the script and you start thinking about themes and stuff like that? Is it fairly early on?

Desplat: Yes, very early on before shooting, and for the next film we’re going to do together, that is just finished and is in editing now. Wes said that I would write music before, so I wrote some ideas before that they used on set, I think.

BTL: How do you start to write and come up with ideas? Do you generally sit down at the piano?

Desplat: I’m not a pianist. Of course, I play piano, but I wouldn’t play in a concert or to perform, but I use the piano to play a melody and themes, something not too “pianistic.” Otherwise, I work on the computer with very precise orchestrated demos that I play to the director.

BTL: Branching off my previous question, are you actually writing a lot of stuff while he’s shooting or before he’s shooting?

Desplat: No, [the new movie is] an exception. I usually wait for the [film to be edited]. Even the director that you know, that you’ve worked with before, people who have been very loyal to me, and I’ve been loyal to them through the years. I still prefer watching the film, because you never know… the script is just paper and ink, and it’s not enough in the end to see the light, the actors, hear their voices, the pace of the film, the pace of the acting. I want to be an actor in a film.

BTL: I’m sure one of these days Wes will find a role for you on one of his films.

Desplat: I meant it metaphorically. I want to compose as if I was on the set with the actors, that’s what I meant.

BTL: I spoke with Randall Poster recently, and it seemed like Life Aquatic was a bit of a turning point, since that was the last song-based soundtrack Wes did, and then you joined him for Fantastic Mr. Fox. He told me that when it comes to scoring, it’s mainly you and Wes in a studio together. Is Wes coming to you with ideas for instruments or things like that? What’s your first conversation with Wes about the music on one of his films?

Desplat: He never plays music for me, and there’s no temp track. It’s always about the fantasy that he has. Let’s take Grand Budapest. [He’ll be like] “Oh, how about we don’t use an orchestra, but we try and put together instruments that are new to Europa,” and then I suggest ideas, sounds. I do demos, I play themes, and it becomes the score, and then together, in my studio, we decide where and how. Then, he takes my demos and goes back to the editing room, and puts everything together as a Swiss clock, and the music really becomes part of the editing of the pace of the film. When we did Mr. Fox, I suggested that we use only small instruments because it was these little puppets. I didn’t want a big score. I think that’s how we started, actually, playing with the instrumentation, with weird, strange instrumentation combinations of sounds. In Mr. Fox, I didn’t want to use full orchestra, so I used little instruments, baby instruments. It creates a very charming, gentle sound, not bombastic, because the movie didn’t need to be bombastic in terms of score.

BTL: The French Dispatch has some really interesting instruments as well. I think I heard tuba, banjo, harpsichord…

Desplat: Bassoons…

BTL: I’m always trying to figure out if there are live musicians or just really good samples, but I assume you always record everything live?

Desplat: There’s no samples, everything’s live. It’s very important for Wes that everything’s live, because he likes to experiment in the studio, “How about we try this or that?” No, my demos are [samples], but they become much better, because it’s real instruments, always.

BTL: So would he say something like, “Let’s try a tuba,” and then you have to find a tuba player?

Desplat: It could be that. In the studio, he could say, “Oh, how about we play the piccolo by the tuba?” “Okay, let’s bring the tuba in.” Yeah, we could do that kind of thing. He has this strategy.

BTL: How have things changed for you with COVID? I’ve spoken to composers who have worked with live orchestras in Vienna using all these crazy apps to sync up between countries. Have you been doing that, too, or just working there in France?

Desplat: Yeah, I did that with George Clooney for The Midnight Sky. We recorded a lot over the DSL from Paris with a great sound connection from Abbey Road, so everything was smooth and easy. Netflix made it very, very, very comfortable for us to work, but it was very painful for me and frustrating, because I like to be conducting. I like to be near the musicians, near the orchestra, and share that moment with them when I hear music for the first time. It was not fun. It was efficient and great, but not as I wish it to be. Many other scores I recorded in Paris. Luckily enough, I could finally go to England a few weeks ago and recorded a new score for Stephen Frears, but my everyday life was the same. I was locked in the studio all day, writing music, but the fun of taking a train or a plane to go record in the bigger studio with musicians, unfortunately, that was not possible. That was sad.

BTL: Does it feel like things have gotten better in the last year and a little closer to going back to normal?

Desplat: No, it’s very new. I mean, I was under to go to Greenland three weeks ago, and America, for the first time I could come yesterday, I arrived yesterday, because it was the first time the borders were open to me. I’ve been very much away because of COVID. I couldn’t be here and work with directors here.

BTL: I always get a kick out of the names of cues on soundtracks, and the ones on French Dispatch are quite witty. Is that you coming up with names for the different pieces?

Desplat: No, that’s Wes. That’s all Wes. Because it’s the name of the characters or the situations and the scenes, so it’s mostly from Wes’ world.

BTL: You work with a lot of other directors and filmmakers as well, a lot of people multiple times as you mentioned. Do any of the other directors you work with use temp music, either your own or someone else’s that they cut to, or do you generally get a dry edit with no music?

Desplat: Well, directors like Wes Anderson, like Roman Polanski, they don’t use temp. They never use temp, they don’t need it, because they have their own idea of what the music should be, and what the editing should be without using temp. Some others, they mix existing scores of mine or other composers. It’s a bit of a battle each time for the director to forget this temp that is heard again and again and again and again and again and again. And again. And again. And again. It’s always difficult to convince him that you can look for another sound, another pace, that the bass is not right, or the sound is not right, or the placement is not right, which is another story all along. I have to deal with it, and I try to convince the director that my choice is best. Sometimes I win, sometimes I lose.

BTL: I’ve spoken to quite a few composers about hearing your own past music over new images, and the composers I’ve spoken to know right away that it’s not the right music for those images. I’m not sure if that’s just a natural knack one has a composer or the instinct of not wanting to lose scoring work to his or her past self. How do you feel about temp music even if it’s your own?

Desplat: There’s this famous scene between Brian de Palma and Bernard Hermann coming to a screening where he used his previous cues, previous music from Hitchcock, and Bernard Hermann just stormed out, saying it was impossible to use that music in this film, because it was wrong. And I understand. When you see a film, and you hear the music that you’ve written for something else, it’s disconnected. It’s just not right. You know that there’s something else that can be cooked by the chef.

BTL: I know you’re working on a few different things, including Stephen Frears’ next movie, which I’m excited for, since it’s been the longest time since a movie from him. Do you generally focus on scoring one movie at a time?

Desplat: Always. It’s too difficult. I’m just by myself in my studio, and I couldn’t do two movies at a time. I don’t want to hire somebody to write in the room beside my room, that’s not what I want to do. I write every single note of my scores, that’s what I love, that’s why I chose that job, because I’m passionate about writing music and orchestrating.

BTL: Can you write something, then work on something else and then do recording or post later, or is it usually one project, beginning to end?

Desplat: Beginning to end, usually.

BTL: It’s great talking to you. The French Dispatch is another one of your great works, and I do have to say that I have listened to the score more than I’ve seen the movie.

Desplat: That’s what I try to do. Some movies are harder to be able to score and write music that can hold, because it’s too much action or maybe you’re not inspired by a scene at that time, but it’s always what you dream of as a composer, to be able to write music for a film that would still be able to be listened to by listeners out of the theater.

BTL: You said that you never want to compose music for a live orchestra to play a concert, but a lot of composers have gone out with an orchestra to perform their music from films, so have you thought about that?

Desplat: Of course, that was when I was 15, but I’ve started to write a concept now. I wrote some pieces for flute and orchestra and I wrote an opera. I’ve started doing something else in between.

BTL: But even just performing some of your film scores…

Desplat: Yes, yes, I’ve done that. Of course, with the COVID, that was basically shut down, but I’ve done many concerts around the world. But there are some concerts coming in Vienna, in Moscow, in Hong Kong, many places… And maybe one day in America.

BTL: That would be nice.

Desplat: I agree.

The French Dispatch is still playing theatrically in select cities and is available On Demand. The Blu-ray and DVD will be released on Dec. 28, and you can hear Desplat’s score for it on all good streaming platforms, such as Spotify.